IT PAYS TO COUNT THE COST

Page 61

Page 63

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Preparation of cost data for own-account transport can be an aid to efficient management decision making

by Johnny Johnson THE EFFECT of transport costs on the finished price of manufactured products can be quite considerable: it can be up to 40 per cent in some cases. This makes it more inexplicable that many manufacturers remain unaware of the true cost of operating their own transport and will cheerfully sanction the delivery of a relatively small order to a customer many miles away using a large vehicle without counting the cost.

While appreciating that the operation of road vehicles to distribute a company's own products has an element of customer convenience, the fact that the vehicle might have to return empty makes the exercise even less economical. Yet that same company will probably be most meticulous. in costing and budgeting the manufacturing process in which it is engaged.

Part of the problem might, in some cases, be that the company accountant, responsible for keeping a critical eye on manufacturing costs, is not conversant with transport procedures and is thus unable to appreciate the implications of excess capacity, empty running or poor schedules. Nor does the production department in many companies realize the advantages in cost and improved deliveries to be gained from planned production in relation to sensible fleet operation.

Despite these difficulties, it is incumbent on the transport manager to establish the true cost of transport to his company, for it is only in this way that transport can take its rightful place as an integral part of management.

For some of the cost factors involved, he will be dependent on information supplied by the company accountant; these might include such items as rent and rates relevant to the transport organization within the company, interest on capital outlay and depreciation of vehicles. So far as the last item is concerned, it is obviously better to depreciate the vehicles on the same basis as that used by the company, to counter any dispute about the validity of costs which might be quoted.

From the same source should come details of overheads incurred. These should include the expenditure involved\on the company's own maintenance facility where this is appropriate as well as heating, lighting, telephone, postage, salaries of administration and maintenance staff and a charge for the buildings which the transport section occupies. Maintenance of directors' and fleet cars should be apportioned separately.

The apportionment of overhead charges to individual vehicles should cause no difficulty. There are many ways of doing this but the most popular seems to be to divide the total overhead costs by the total carrying capacity of the fleet. This gives a figure for overhead costs per ton. The carrying capacity of the particular vehicle concerned is then multiplied by the overhead cost per ton and an individual overhead cost per vehicle is obtained.

Other factors involved can be obtained from the day-to-day vehicle records and the wages bills. They are excise licence duty, drivers' remuneration, insurance, fuel, lubricants, tyre costs and maintenance charges.

Once the relevant standing and running costs have been compiled, it should be a simple matter to produce total costs per journey, per ton, per drop or per package, whichever is relevant to the product being carried.

Advantages Possession of this information has many advantages to the own-account transport manager. First, of course, is the ability to monitor the performance of each vehicle in contrast to others of a similar type within the fleet. Large variations in performance will highlight possible defects or suggest that a vehicle should be replaced. It also provides justification to management that replacement of a vehicle is financially sound, even if this is before the end of its planned life.

Comparative costs are also a guide to vehicle selection. Different makes of vehicles will give different results according to the type of operation to which they are subject. In a mixed fleet, it will soon become apparent which of the vehicle types is more appropriate to the product carried and the distances run and renewal can be based on the better vehicle performance.

Unit costs can often reveal the suitability of the vehicle for a particular

operation and can lead to a reasoned case for replacing existing vehicles with larger or smaller types.

For instance, a 10-ton-capacity vehicle might habitually be loaded with only 6 tons, which could be carried comfortably on an 8-ton-capacity unit.

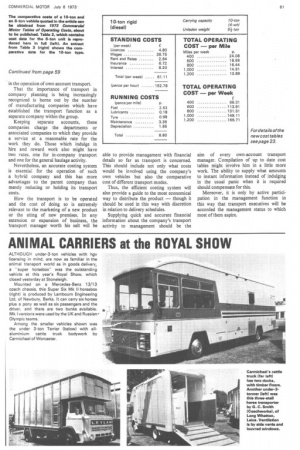

Using the figures given in Commercial Motor Tables of Operating Costs 1973,

to be published shortly, the total operating cost per mile for the 10-ton vehicle is 16.44p and for the 8-ton vehicle 15.60p. In both cases it has been assumed that the vehicles cover 800 miles a week.

To carry 6 tons for 100 miles in the 8-ton vehicle costs £15.60 or £2.60 a ton and to carry the same load over the same distance in the 10-ton vehicle will cost £16.44 or £2.77 a ton.

Margin The creation of 17p a ton reduction in transport cost (representing about 6 per cent) gives a margin for negotiation in the price of the product which might well be considered urgent in making a good case for replacing the larger vehicle with the smaller.

This is a simple example, which can be varied according to the unit cost most appropriate to the product marketed. Nevertheless, it illustrates the influence that costing can have on the selling price of the finished article. Alternatively, it demonstrates that judicious vehicle selection and sensible use of transport can create a larger profit margin with little or no extra investment of capital.

Co-operation with the production department can also result in more economical transport operation and often provide a better delivery service to customers. A suggestion from the transport manager that a slight alteration in production schedules could be made, to coincide with transport availability, might be viewed with suspicion. It is natural for one departmental head to feel that the suggestion has been made for the convenience of the department from which the suggestion comes. But accompanied by details of costs involved together with the savings to be achieved, such a proposal should be irrefutable. No responsible production director or manager would refuse to listen.

In this context, it is always an advantage to be able to point out that half a ton of urgent freight, which is wanted up in Aberdeen by next day, is going to cost an exorbitant amount per ton if sent by own transport to ensure that it arrives in time. An exaggeration perhaps, but circumstances similar to this do arise in the operation of own-account transport.

That the importance of transport in company planning is being increasingly recognized is borne out by the number of manufacturing companies which have established the transport function as a separate company within the group.

Keeping separate accounts, these companies charge the departments or associated companies to which they provide a service at a reasonable rate for the work they do. Those which indulge in hire and reward work also might have two rates, one for in-company transport and one for the general haulage activity.

Nevertheless, an accurate costing system is essential for the operation of such a hybrid company and this has more advantages to the parent company than merely reducing or holding its transport costs.

How the transport is to be operated and the cost of doing so is extremely relevant to the marketing of a new product or the siting of new premises. In any extension or expansion of business, the transport • manager worth his salt will be

able to provide management with financial details so far as transport is concerned. This should include not only what costs would be involved using the company's own vehicles but also the comparative cost of different transport modes.

Thus, the efficient costing system will also provide a guide to the most economical way to distribute the product — though it should be used in this way with discretion in relation to delivery schedules.

Supplying quick and accurate financial information about the company's transport activity to management should be the aim of every own-account transport manager. Compilation of up to date cost tables might involve him in a little more work. The ability to supply what amounts to instant information instead of indulging in the usual panic when it is required should compensate for this.

Moreover, it is only by active participation in the management function in this way that transport executives will be accorded the management status to which most of them aspire.