Problems of the

Page 64

Page 65

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

HAULIER AND CARRIER

Making Contracts With Farmers for Beet Haulage. Fixed Prices for Comparison With the Haulier's Own Costs

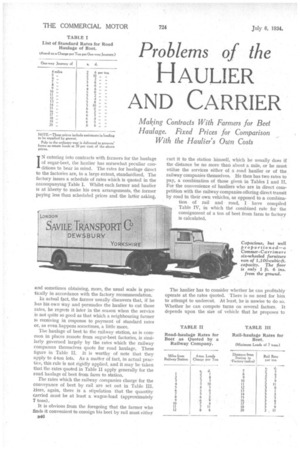

IN entering into contracts with farmers for the haulage of sugar-beet, the haulier has somewhat peculiar conditions to bear in mind. The rates for haulage direct to the factories are, to a large extent, standardized. The factory issues a schedule of rates which is quoted in the accompanying Table I. Whilst each farmer and haulier is at liberty to make his own arrangements, the former paying less than scheduled prices and the latter asking, and sometimes obtaining, more, the usual scale is practically in accordance with the factory recommendation.

In actual fact, the farmer usually discovers that, if he has his own way and persuades the haulier to cut those rates, he regrets it later in the season when the service is not quite so good as that which a neighbouring farmer is receiving in response to payment of standard rates or, as even happens sometimes, a little more.

The haulage of beet to the railway station, as is common in places remote from sugar-beet factories, is similarly governed largely by the rates which the railway companies themselves quote for road haulage. These lig-ure in Table II. It is worthy of note that they apply to 4-ton lots. As a matter of fact, in actual practice, this rule is not rigidly applied, and it may be taken that the rates quoted in Table II apply generally for the road haulage of beet from farm to station.

The rates which the railway companies charge for the conveyance of beet by rail are set out in Table III. Here, again, there is a stipulation that the quantity carried must be at least a wagon-load (approximately 7 tons).

It is obvious from the foregoing that the farmer who finds it convenient to consign his beet by rail must either B46 cart it to the station himself, which he usually does if the distance be no more than about a mile, or he must utilize the services either of a road haulier or of the railway companies themselves. He then has two rates to pay, a combination of those given in Tables f and II. For the convenience of hauliers who are in direct competition with the railway companies offering direct transit

by road in their own vehicles, as opposed to a combination of rail and • road, I have compiled Table IV, in which tim combined rate for the

consignment of a ton of beet from farm to factory is calculated.

The haulier has to consider whether he can profitably operate at the rates quoted. There is no need for him to attempt to undercut. At least, he is unwise to do so.

Whether he can compete turns on several factors. It depends upon the size of vehicle that he proposes to use and upon the willingness of his men to load and unload as quickly as they reasonably can. Such efficiency is generally ensured by paying a small bonus, usually about 1d. per ton, to be awarded at the end of the season. More than anything, however, the potentiality for profit making is determined by delays in loading and unloading and of these the latter are more prevalent.

If the haulier be concerned' only with loads for the railway station, it is not likely that he will meet with much difficulty on this account. Congestion at railway goods yards never approaches in its intensity that which prevails at moat of the beet factories.

It is usual and preferable to employ two men per vehicle, as only in that way is the most economical working possible. The figures which I give in Table V give some measure of the haulier's ability to compete against the railway companies for loads to the station and, generally, when hauling to a factory, where the delays are insignificant.

The basis of the calculation of these rates is the figures given in The Commercial Motor Tables of Operating Costs, for, although some items of cost are less in the country, provision has to be made for the wages of the extra man. The actual basis is as follows :-For a 2tonner, 3s. 64. per hour and 3d. per mile ; 3-tanner, 4s. per hour and 4d. per mile;' 4-tonner, 45. 64. per hour and 5d. per mile ; 5-tanner, 5s. per hour and 54,d. per mile ; 6-tonner, 5s. 3d. per hour and eid, per mile, and a 7-former, 5s. ed. per hour and aid. per mile.

A fair rate of loading and unloading beet is 20 minutes per ton per man, that is to say, 10 minute's per ton with two men. Sometimes unloading is expedited at the factory and at the railway goods yard, in the first case when

the Effra water jet can be used, or in both cases when the beet can be tipped. It is not, however, advisable to take this into consideration, as there are, as a rule, other causes of delay. For example, it is generally necessary to wait turn to place the vehicles under the jet or to tip. I have, therefore, taken an average of 20 minutes per ton to cover loading and unloading.

How that figure applies may readily be realized if I point out that it means that, for a 3-tonner, an hour is regarded as being necessary for loading and unloading and for a 6-tonner two hours. Other sizes take time in proportion to the load. Assuming an average speed of 30 m.p.h. in the case of 2-tonners, four minutes must be allowed per mile of journey (involving two miles of travelling). For larger vehicles I have taken five minutes.

For each mile of lead there must be allowed, in the case of a 2-tonner, say, the cost of four minutes, roughly 24., plus ed. for two miles of running, totalling 8d. per mile lead. Corresponding figures for the other sizes are : 3-tonner, is.; 4-tonner, Is. 24.; 5-tonner, Is. 4d.; 6tonner, is. 6d. and 7-tonner is. 74.

As a simple example, assume the case of a 5-tormer engaged on a 10-mile lead. The time for loading and unloading is 1 hour 40 minutes, which, at 5s. per hour, is Ss. 44. The 10-mile lead at 1s. 4d. per mile costs 13s 4d. The total is 21s. Sd., or 4s. 4d. per ton.

If deliveries be made to a factory where delays are rife and if the average delay be 1i hour, that adds 7s. 6d. to the charge, bringing it to 29s. 2d., or 5s. 10d. per ton. The factory rate is 5s. per ton, which, with no delays, would be profitable. With the usual delay, it is not so. Table VI is calculated on the basis of an average delay of 1i-hour per load.