BUILDING ON STRENGTH

Page 44

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Neville Charrold is well known for its top-selling aluminium tipper bodies. It has not made a loss in 19 years, still has a long waiting list and aims to stay ahead of the field.

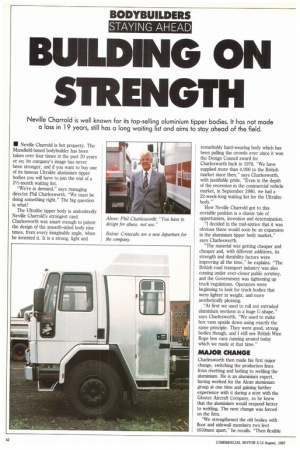

• Neville Charrold is hot property. The Mansfield-based bodybuilder has been taken over four times in the past 20 years or so; its company's image has never been stronger, and if you want to buy one of its famous Ultralite aluminium tipper bodies you will have to join the end of a 21/2-month waiting list.

"We're in demand," says managing director Phil Charlesworth. "We must be doing something right." The big question is what?

The Ultralite tipper body is undoubtedly Neville Charrold's strongest card. Charlesworth was smart enough to patent the design of the smooth-sided body nine times, from every imaginable angle, when he invented it. It is a strong, light and

remarkably hard-wearing body which has been pulling the crowds ever since it won the Design Council award for Charlesworth back in 1976. "We have supplied more than 4,000 to the British market since then," says Charlesworth, with justifiable pride. "Even in the depth of the recession in the commercial vehicle market, in September 1980, we had a 22-week-long waiting list for the Ultralite body."

How Neville Charrold got to this enviable position is a classic tale of opportunism, invention and determination.

"I decided in the mid-sixties that it was obvious there would soon be an expansion in the aluminium tipper body market," says Charlesworth.

"The material was getting cheaper and cheaper and, with different additives, its strength and durability factors were improving all the time," he explains. "The British road transport industry was also coming under ever-closer public scrutiny, and the Government was tightening up truck regulations. Operators were beginning to look for truck bodies that were lighter in weight, and more aesthetically pleasing.

"At first we used to roll out extruded aluminium sections in a huge U-shape," says Charlesworth. "We used to make box vans upside down using exactly the same principle. They were good, strong bodies though, and I still see British Wire Rope box vans running around today which we made at that time."

MAJOR CHANGE

Charlesworth then made his first major change, switching the production lines from rivetting and bolting to welding the aluminium. He is an aluminium expert, having worked for the Alcan aluminium group at one time and gaining further experience with it during a stint with the Gloster Aircraft Company, so he knew that the aluminium would respond better to welding. The next change was forced on the firm.

"We strengthened the old bodies with floor and sidewall members two feet (610nun) apart," he recalls. "Then flexible truck chassis came along and they started to break the bodies." Each body member would need to cope with 30inm expansion movements on the new generation of chassis.

"My theory," says Charlesworth, "was to drop the strengthening members and to make the whole design longitudinal, allowing the unit to expand with the chassis lengthwise. It took me six months to convince the men here that it was a good idea."

He did so, however, and the first unit is still at work out in the field somewhere, 12 years after the prototype left Charlesworth's drawing board.

There were several unique selling points on the Ultralite body which helped notch up sales. It is plain-sided and not ribbed, making it easier to wash and to livery.

There are still plenty of ribbed tipper bodies around which need to be fitted with signboards before the haulier can paint or transfer his name on the side. The Ultralite gets round these inconveniences, while its plain aluminium finish also does away with the need for paint, and the weight of that paint. It is easy to insulate and Neville Charrold kits out a lot of the bodies with 75mm-thick Rocksil bonded GRP wool resin.

MAGIC INGREDIENT

The magic ingredient to the Ultralite body is the U-shaped extruded beams which run underneath the body's entire length. They are torsionally strong and can cope with 25% overloads by deflecting 50mm, says Charlesworth. The beams are made overseas to Charlesworth's design, and owe quite a big debt to aircraft design techniques. "When a lorry goes round a traffic island, the body will bend five times," he says.

It took five years to find someone to build the beams to Neville Charrold's exact specifications, but Charlesworth was determined to follow the plan through precisely. He is used to pioneering work.

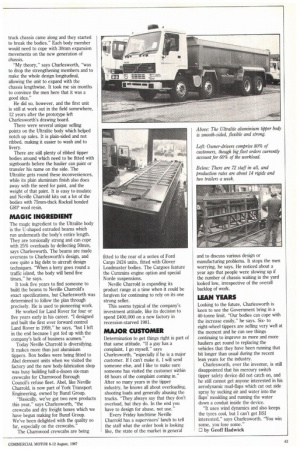

He worked for Land Rover for four or five years early in his career. "[designed and built the first ever forward control Land Rover in 1959," he says, "but I left in the end because I got fed up with the company's lack of business acumen," Today Neville Charrold is diversifying. It makes more than just aluminium tippers. Box bodies were being fitted to Abel demount units when we visited the factory and the new body-fabrication shop was busy building half-a-dozen six-man crewcabs for Charnwood Borough Council's refuse fleet. Abel, like Neville Charrold, is now part of York Transport Engineering, owned by Bunzl Group.

"Basically, we've got two new products this year," says Charlesworth, "the crewcabs and dry freight boxes which we have begun making for Bunzl Group. We've been delighted with the quality so far, especially on the crewcabs."

The Charnwood crewcabs are being fitted to the rear of a series of Ford Cargo 2424 units, fitted with Glover Loadmaster bodies. The Cargoes feature the Cummins engine option and special Norde suspensions.

Neville Charrold is expanding its product range at a time when it could be forgiven for continuing to rely on its one strong seller.

This seems typical of the company's investment attitude, like its decision to spend 2400,000 on a new factory in recession-starved 1981.

MAJOR CUSTOMER

Determination to get things right is part of that same attitude. "If a guy has a complaint, I go myself," says Charlesworth, "especially if he is a major customer. If I can't make it, I will send someone else, and I like to make sure someone has visited the customer within 48 hours of the complaint coming in." After so many years in the tipper industry, he knows all about overloading, shooting loads and generally abusing the trucks. "They always say that they don't overload, but they do. In the end you have to design for abuse, not use."

Every Friday lunchtime Neville Charrold has a supervisors' lunch to tell the staff what the order book is looking like, the state of the market in general and to discuss various design or manufacturing problems. It stops the men worrying, he says. He noticed about a year ago that people were slowing up if the number of chassis waiting in the yard looked low, irrespective of the overall backlog of work.

LEAN YEARS

Looking to the future, Charlesworth is keen to see the Government bring in a 40-tonne limit. "Our bodies can cope with the increase easily," he says. Sixto eight-wheel tippers are selling very well at the moment and he can see things continuing to improve as more and more hauliers get round to replacing the vehicles that they have been running that bit longer than usual during the recent lean years for the industry.

Charlesworth, ever the inventor, is still disappointed that his mercury switch tipper safety device did not catch on, and he still cannot get anyone interested in his aerodynamic mud-flaps which cut out side spray by sucking air and water into the flaps' moulding and running the water down a conduit inside the device.

"It uses wind dynamics and also keeps the tyres cool, but I can't get BSI interested," says Charlesworth. "You win some, you lose some."

I=1 by Geoff Hadwick