costing for maximum profit

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

A SPECIAL SERIES BY R. P. C. BLOCK

6. The Flow-line ingredients to produce total operating costs

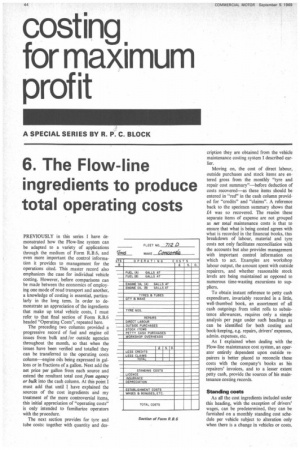

PREVIOUSLY in this series I have demonstrated how the How-line system can be adapted to a variety of applications through the medium of Form R.B.6, and even more important the control information it provides to management for the operations cited. This master record also emphasizes the case for individual vehicle costing. However, before comparisons can be made between the economics of employing one mode of road transport and another, a knowledge of costing is essential, particularly in the long term. In order to demonstrate an appreciation of the ingredients that make up total vehicle costs, I must refer to that final section of Form R.B.6 headed "Operating Costs", repeated here.

The preceding two columns provided a progressive record of fuel and engine oil issues from bulk and/or outside agencies throughout the month, so that when the issues have been verified and totalled they can be transferred to the operating costs column—engine oils being expressed in gallons or in fractions of a gallon. Next add the net price per gallon from each source and extend the resultant total cost from agency or bulk into the cash column. At this point I must add that until I have explained the sources of the cost ingredients and my treatment of the more controversial items, this initial appreciation of "operating costs" is only intended to familiarize operators with the procedure.

The next section provides for tyre and tube costs: together with quantity and des

cription they are obtained from the vehicle maintenance costing system I described earlier.

Moving on, the cost of direct labour, outside purchases and stock items are entered gross from the monthly "tyre and repair cost summary"—before deduction of costs recovered—as these items should be entered in "red" in the cash column provided for -credits" and "claims". A reference back to the specimen summary shows that £4 was so recovered. The reason these separate items of expense are not grouped as net total maintenance costs is that to ensure that what is being costed agrees with what is recorded in the fmancial books, this breakdown of labour, material and tyre costs not only facilitates reconciliation with the accounts but also provides management with important control information on which to act. Examples are workshop labour output, the amount spent with outside repairers, and whether reasonable stock levels are being maintained as opposed to numerous time-wasting excursions to suppliers.

To obtain instant reference to petty cash expenditure, invariably recorded in a little, well-thumbed book, an assortment of all cash outgoings from toilet rolls to subsistence allowances, requires only a simple analysis per page under such headings as can be identified for both costing and book-keeping, e.g. repairs, drivers' expenses, admin. expenses, etc.

As I explained when dealing with the Flow-line maintenance cost system, an operator entirely dependent upon outside repairers is better placed to reconcile these costs with the company's books as his repairers' invoices, and to a lesser extent petty cash, provide the sources of his maintenance costing records.

Standing costs As all the cost ingredients included under this heading, with the exception of drivers' wages, can be predetermined, they can be furnished on a monthly standing cost schedule per vehicle subject to alteration only when there is a change in vehicles or costs. Easy reference to the schedule reduces this part of the cost analyst's task to simple copywork.

Any attempt to allocate drivers' remuneration to specific vehicles involves laborious and, in my view, unnecessary recording, particularly where there is a large labour turnover and drivers have to be switched from one vehicle to another. For costing, the important requirement is to absorb the actual total payroll per month, which for calendar month costing amounts to taking 4+ weeks per month, i.e. 52 weeks per annum—a reconciliation being made quarterly between costing and actual payroll.

To do this, take the total gross pay including bonuses for ALL the road staff for the relevant four or five pay weeks in the month being costed and then calculate the average total payroll per week—dividing by four or five, whichever is appropriate. The resultant when multiplied by 4+ is the calendar month's total pay to be costed.

Next, total the hours worked by all the drivers as recorded on Forms R.B.6 and divide the total into the calendar month's payroll, giving an average hourly rate per driver. Finally, multiply the average hourly rate by the total number of hours recorded on each R.B.6 and extend the resultant cost into the cash column against "wages and bonuses, etc".

The same formula is applied to calculate the workshop operatives' average hourly rate but multiplying by the total number of hours booked on each job sheet raised for any vehicle or trailer on which time has been recorded, including time booked to "Overhead A IC".

Depreciation is the estimated annual cost of the reduction in the value of the vehicle/ trailer over its economic life. Some will say that this should be calculated on a mileage basis and, therefore, as a, cost per mile. Space does not permit me (0 argue the point here, but as it is a most important cost ingredient because of MoT tests and the more stringent maintenance standards required, I shall explain the principles involved in a later article illustrating the differences in approach between company and Inland Revenue allowances. In the meantime, think about the yardstick exercising a purchaser's mind when he is offered a vehicle for sale, e.g. is it age or mileage?

Establishment costs constitutes a variety of administrative expenses, the sum total of which has to be allocated in an equitable form over the number of earning vehicles. As with workshop overheads, it is a cost which differs considerably between one operator and another and as they can contain many "hidden costs" these ingredients will be explored in the next instalment.

Do bear in mind, however, that while we have been looking at the cost items that contribute to the completion of the final column of R.B.6 someone should already be employed in processing the information being recorded on drivers' log sheets, fitters' time sheets and repairers' and stockists' invoices; consequently, until that major arrea of Form R.B.6 has been completed, I can use the intervening period to resolve the outstanding and more questionable items to which I have previously referred.