Three times weekly to Asia Minor

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by lain Sherriff

BACK in 1965 Mike Woodman, the founder and managing director of Asian Transport Ltd, was described as an adventurer when he sent a 1962 Guy Warrior with a York Freightmaster semitrailer to Kabul on three trips carrying Linotype machines. Adventurer he might have been but successful he certainly was. Mike Woodman and his fellow director David Paul now operate 12 vehicles of their own and hire-in a further 12 vehicles from European operators. All the vehicles are engaged on regular hauls to Istanbul, Ankara and Tehran. They also make special runs to destinations around the Persian Gulf and out as far as Islamabad. Karachi, Muscat and Jeddah.

The extent of the company's operations can best be judged in financial terms. Last year the turnover was in excess of i+m and the value of the goods carried exceeded £6m. The fleet, including the hired vehicles, travelled one million miles.

Since 1965 Asian Transport has given birth to a very healthy offspring, Astran International Ltd. It became apparent to the directors of Asian that shipping and forwarding was a more profitable exercise than pure haulage. where cut-throat operators poached business at uneconomic rates. Astran International Ltd became the company which looked after shipping, forwarding, insurance and packing and Asian Transport adopted the role of the road transport subsidiary.

Another factor which persuaded the company to diversify was customer demand. A number of their existing customers who had used Asian Transport with satisfaction then asked for air freight facilities for smaller packages. Others chose to send some of their goods by the long sea route but at that time Asian Transport had to turn this type of traffic away. Today Astran International handles all types of traffic using every mode of transport but, of course, the emphasis is on road transport.

The 12 company vehicles are equally divided between Scania 110 and 140 and Volvo FB88 with either Crane Freuhauf or Merriworth semior drawbar trailers. The Guy was replaced with a Scania because, in Mike Woodman's words, "Neither it nor any other British vehicle, at that time, was built for rough terrain between Turkey and the Gulf". But Mike Woodman is not a dedicated foreign vehicle operator. Referring to CM's description of the Leyland Marathon (CM August 31) he said: "I see that at last British Leyland has produced a vehicle to challenge the continentals. I would dearly love to buy British and I sincerely hope that the Marathon can stand up to our work".

In developing the market beyond Turkey, Mike Woodman set himself a mammoth task. The roads are not ideally suited for 32-ton vehicles and scheduling is made difficult through domestic circumstances, like local holidays, customs arrangements — or the lack of them — and language problems.

Dealing with this last problem first, all of Astran's Middle East documentation is printed in Arabic and this helps to smooth the way with agents. The company has no depots of its own in these faraway places but uses good, commercially minded agents to clear consignments and organize backlo ads.

Mike Woodman has made a point of covering the area regularly by car so that he knows the terrain almost as well as he knows the lanes of Kent around his Chislehurst office. But more important, perhaps, he knows when Middle East commerce comes to a standstill because of holidays and when customs posts are closed.

For example, the weekend holiday in the Persian Gulf is Thursday and Friday. It is therefore pointless for a driver arriving on a Wednesday evening expecting to get discharged before Saturday morning.

At the British end of the operation, however, the office has to be manned for seven days because cables, telephone calls and the isolated Telex message are often transmitted on Saturdays and Sundays.

Drivers, whether company employees or hired-in, are required to report by the fastest available Means every third day. This is a progress report which is passed on to the customers whose cargo is in transit. The flexibility of the schedule ("That's just another term for traffic delay", says Mike Woodman) is absolutely essential and customers accept that, on such a run, delays can occur. Nevertheless, three vehicles leave the UK each week for Tehran and cargo to the Gulf normally takes 2+ weeks to deliver.

Generally speaking, drivers are away from home for around four weeks at a time and when they send their cable from Istanbul on the homeward leg the clerks in the traffic office at Chislehurst breathe a sigh of relief. "We consider by that time he's nearly home", said Mike Woodman.

Such an operation, of course, has the attendant problem of driver availability. But the company appears to have been fortunate in being able to recruit the right type of man. I was told that drivers normally remain with Asian Transport for three years and more.

On their return from a four-week trip they can enjoy anything from one week to 10 days at home. Their vehicle is customs-cleared and discharged for them. It is then taken to the company's engineering department at Norfolk where it is thoroughly overhauled and reloaded ready for another long haul.

The job attracts drivers who seek a bit of glamour with their work. Rut many of them have been recruited on the "xommendation of established drivers who meet up with them and cravel in convoy with them across Asia Minor. "When you have travelled behind a man for a thousand miles, you hare a fair idea of his ability", said Mike Woodman.

In the forefront of every operator's mind is the question of spares availability. How much more important this is when vehicles are operating so far from home under far-from-ideal conditions. No matter how well a vehicle is serviced no-one can guarantee that it will not require some kind of attention in the mountains of Turkey or on the dust roads of the Great Salt Desert.

There are manufacturers' agents in these isolated areas but they could be hundreds

of miles from the vehicle when it needs attention. Another snagis that each territory allows only single-manufacturer franchises so that if you break down with a Scania in "Leyland country" or vice versa then you can be a very long way from a spare part. When engine components go there is nothing for it but a flight from the UK.

Peter Cannon, the company's transport manager, recently carried two pistons all the way to Adana, had them fitted and was back in Norfolk in 72 hours. Mike Woodman points out that as he quotes through rates, delays can be very costly — customer delays of course incur demurrage.

The fact that Asia Minor is not a highly industrialized part of the world works on occasion to the advantage of the operator. If a spring breaks in Turkey a new one is made by the local blacksmith and fitted in a few hours, faster indeed than in many cases at home when a replacement spring would be used. On one occasion a Scania propshaft snapped and a local blacksmith was called in to weld it. Scania warned Peter Cannon that welding a propshaft was impossible and that it could not possibly stand up in service. A replacement was delivered to Norfolk to await the vehicle's return from Kabul. It says much for the Turkish blacksmith that the repaired shaft made another two trips to the Persian Gulf before it was replaced.

With a company like Astran, expansion seems inevitable and in the not too distant future we can expect to see them workiximp much nearer home in Northern Europe.

Mike Woodman suggested that a Paris office was a distinct possibility since his wife is French. It is equally certain, however, that the Middle East operations will not suffer. In fact, expansion throughout Europe and Asia Minor could take place now but for two factors — permits and drivers.

These considerations already influence the company's operation. Appreciating that there is a very limited market for class 1 hgv drivers and that his company demands more of a man than almost any other operator in Britain, Mike Woodman considers himself fortunate in having 12 top-quality men. He views the permits situation just as philosophically and this is why he hires Dutch operators for much of his operation. They have the permits, they have the vehicles and the drivers.

Before engaging a sub-contractor his documentation is scrutinized, his financial standing examined and his insurance coverage checked out and then Mike Woodman demands a sight of the allimportant permit. Sub-contractors are engaged either for the trip out, the round trip or on a long-term basis. The latter method is of course the most satisfactory for all parties concerned.

There is no sales force at either Astran or Asian yet there are full order books. Mike Woodman puts this down to the type of service he is offering, where satisfied customers become company salesmen merely by recommending the service to other exporters.

Others have tried to service the Asia Minor market. "They have looked at £15,000 contracts and gleefully rubbed their hands", Mike Woodman told me. "However, because they did not cost the exercise properly they finished up burning their fingers".

The road haulage industry is not given to quoting rates freely to the Press lest competitors jump in and undercut. Mike Woodman has no such inhibitions. He gave me two examples showing how road compared with sea and air. The first

s a shipment of hitavy machinery of four items each weighing 10 Rijn and occupying 25 cu m to be taken from Birmingham to Kuwait. The sea and air times and rates, he says, are reduced to the bare minimum. These are his figures.

SEA 1. Handling. UK 587 2. Sea freight 2,936 3. Handling. Kuwait 240

£3.736 (Transit time: 6 to 8 weeks). (Transit time: 3 to 5 days)

These, of course, are unit loads, while most of Astran's traffic is groupage. An example of part-load costing is a 2-ton shipment in cartons occupying 6 Cu m on a trailer between London and Tehran. Again Mike Woodman supplied figures for all three modes:

SEA 1. Handling, UK 18 2. Sea freight to Gulf Port 192 3. Handling & onforwarding, Iran 40

When comparisons like these are presented to exporters there is little doubt about the mode of transport they choose. Perhaps there is a lesson here for the road haulage industry in presenting its case — whether to domestic or international customers.

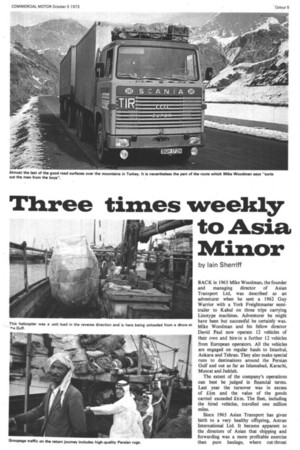

Astran's traffic includes spare parts, textiles, confectionery, raw materials, machinery, furniture removals, electronic components, oilfield equipment, ships' spares and pharmaceuticals. For return load traffic they depend largely on high-value Persian rugs, nuts and citrus fruits but they have carried more unusual consignments in both directions. For example anormour-plated Rolls-Royce for the Shah of Persia and a "clapped out" helicopter coming to Britain for repair.

Another service offered by the company is that of progress chasing orders. The Basra Oil Company place an order for supplies on a British supplier and send a copy of the order to Astran who employ an expediter whose job it is to chase the order and then progress it right through to the Gulf. It is this kind of service which has seen the company grow from a onevehicle adventurer to a 4m-turnover commercial enterprise.