A EUROPEAN CRUSADER

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Trevor Longcroft

THERE is good haulage business to be had in Europe, but it is all too easy to get one's fingers burned on international work, as a fair number of operators have discovered to their cost.

Sustained success depends not so much in finding good traffic flows at economic rates as on having vehicles, equipment, communications and above all drivers who are right for the job.

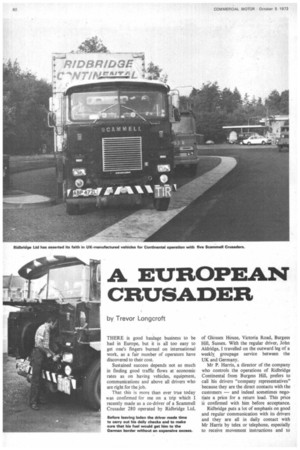

That this is more than ever true today was confirmed for me on a trip which I recently made as a co-driver of a Scammell Crusader 280 operated by Ridbridge Ltd, of Glossex House, Victoria Road, Burgess Hill, Sussex. With the regular driver, John Aldridge, I travelled on the outward leg of a weekly groupage service between the UK and Germany.

Mr P. Harris, a director of the company who controls the operations of Ridbridge Continental from Burgess Hill, prefers to call his drivers "company representatives" because they are the direct contacts with the customers — and indeed sometimes negotiate a price for a return load. This price ii confirmed with him before acceptance.

Ridbridge puts a lot of emphasis on good and regular communication with its drivers and they are all in daily contact with Mr Harris by telex or telephone, especially to receive movement instructions and to enable ferry bookings to be made according to an individual vehicle's progress. In the UK and for high-security loads, the drivers can use radio to keep in touch with the office or with Securicor.

I met the vehicle and Mr Aldridge at the cargo pick-up point in East London. Our drop-off points were Cologne, Mainz and Frankfurt. But before we could load, the fork-lift trucks used in the loading bay broke down. We were delayed for approximately 24 hours and we made arrangements to rebook a later ferry crossing from Dover to Zeebrugge.

Clearing Customs When we arrived at Dover we were delayed at Customs while our T3 and T document numbers were transcribed on to our shipping orders, a copy of which has to be given to each Customs post we passed through.

On the ferry we were able to grab a few hours sleep and a quick meal before disembarking at Zeebrugge. All our documents were in order and it took only 10 minutes to clear Customs. As we were to take turns driving we hoped to make up most of the time lost in London.

But for a short section of city traffic conditions in and around Brussels the road to Germany was autobahn. There was very little traffic, and good progress could be made — but even this early in the trip we encountered an example of the inadvisability of sending raw drivers abroad without detailed and experienced briefing.

A British driver whom we had met on the boat asked if he could follow us because he was not sure of the way. Judging by the small clearance between his truck's driving-axle wheels and wings he was grossly overloaded, and he had some difficulty in keeping up with us — especially as we were running at an all-up weight of only 23 tons.

Fuel levy To cap it all, the man was obviously ignorant of the German fuel tax, and at the Belgian/German border at Aachen he needed most of his German currency to pay for the excess in his tank. By contrast John Aldridge had checked the fuel tank before leaving London to ensure that we had just enough, with a small margin, to reach Aachen, since the German authorities levy a tax on any fuel in excess of 50 litres entering the country. We had six gallons over the limit, and had to pay £2.50.

The fuel tanks are physically checked before the vehicles leave the Customs area, so a false declaration would be in vain. When leaving Germany one can get a credit on any excess fuel taken out, to offset against any excess on the next entry into the country.

Both the Belgian and German frontier officials maintained a rather officious aloofness while clearing our papers and John Aldridge waited a few minutes so as to use his fluent German to assist the other British driver with his form filling and so on.

Pushir. ig on towards Cologne we encount

erect the typical restrictions placed on trucks on the autobahn. On some uphill sections heavy trucks are forbidden to overtake. while on other sections the second (overtaking) lane is covered by maximum weight limits that vary according to road conditions.

I found to my cost that these restrictions are rigidly enforced. I misread a road sign and overtook in a prohibited zone. Within minutes we were flagged down by the West German police and politely but firmly told that I had been fined the equivalent of £10 on the spot.

Again, Mr Aldridge's German proved its value, as he tactfully explained how the error has occurred and apologized profusely for my unintentional law-breaking. 1 learned later that I had got off lightly.

It was 4 am as we reached the approaches to Cologne, so rather than arrive at our dropoff point hours early we took the opportunity to have a short sleep and take some light refreshment. We rolled on to our comfortable bunks and slept.

Our English "shadow" was still with us, and did not enjoy the benefits of a sleepercab. Even operators who disapprove of their drivers sleeping in the cabs, and insist on them taking proper accommodation, seem to overlook the fact that on the Continent a man virtually lives with his vehicle and there are many occasions when unexpected delays provide a chance to get some rest.

Rush-hour traffic On this occasion the driver of the other vehicle had to make do with a makeshift bunk which folded down over the driver and passenger seat, while his co-driver had to sleep on the grass verge!

Before leaving this stop, Mr Aldridge bought a street map of Cologne and decided on the best route to take to the first drop. By entering Cologne on the correct road we were able to avoid a lot of rush-hour traffic and save time. We drove straight to the pick-up point, quickly dispensed with the paperwork formalities and waited only a few minutes before starting to unload.

The rest of the journey to Mainz and Frankfurt passed without mishap. As with Cologne we bought a street map for each city and reached the drop-off point without difficulty. When we arrived in Frankfurt a return cargo had already been arranged and I left him on his way to pick it up. The load was to be picked up the following day and he was going to take his statutory rest period before continuing home. • As well as rigidly controlling heavy vehicles on the motorways, West Germany — in common with some other countries — prohibit the movement of heavies at weekends or on Bank Holidays unless they are carrying perishable cargoes or are heading for home. In any case, as John Aldridge said, if the German police said "No" you stopped where you were, so he was pleased to have obtained a return load immediately. A delay could have meant a wasted weekend in Frankfurt.

Apparently the police are more likely to let a heavy truck proceed if it can match the speed of the autobahn, so John Aldridge said that he appreciated the performance of the Scammell. (A minimum power-toweight ratio of 8 bhp per ton becomes mandatory for German heavies registered from January 1 next).

One notable feature of the trip was the absence of British vehicles: I saw only a handful during the two days that I was on the road.

Because we were only loaded to 23 tons gross it was difficult to relate the performance of the Cru.sader to other vehicles on the. road which, because of their lower speeds, I concluded were fully laden.

On the autobahn the Scammell easily kept to the maximum legal speed limit and generally the top gear of the eight-speed Fuller box was typical for the route. Because of the continual usage of the nearside lane by heavy vehicles the road surface had been deeply rutted where the road wheels ran. Over these sections the Crusader tended to pitch — the absence of any substantial load on the fifth-wheel probably made the situation more noticeable than had it been fully laden. However, when the vehicle pitched, it became difficult to maintain a constant throttle opening and the combination of pitch and changing throttle position produced a stop-surge effect which could be corrected only by briefly closing the throttle at intervals. On flat road surfaces, ride was acceptable for a tractive unit.

Minor faults I like the inside-cab layout. However, Mr Aldridge felt that there were a few minor faults which could be cheaply rectified. For instance, the twin bunks are fixed in the down position. The lower restricts the rearward movement of the driver seat and on rough sections of road when the driver was jerked it was easy for him to hit his head on the top bunk. An easy remedy is to let the bunks fold back, say, 45 degrees — this increases the seat travel and the luggage stowed on the bunks then would not shoot on to the floor at each abrupt stop.

Finally, said Mr Aldridge, he would appreciate somewhere to hang a suit.

Mr Harris operates a total of seven artic outfits, and all are involved on overseas operation. He has five 280 Scammell Crusaders, one Mercedes LPS 2024 and a Volvo F88. He is very pro-British and says that he expects his fleet to remain predominantly Crusader.

Later models, he says, will be fitted with a higher 5.40 to 1 rear axle with dill lock, in order to improve fuel consumption and take the top speed to 64 mph. The dill lock has obvious advantages when running in winter conditions.

Each vehicle is supplied with two spare wheels — unit and trailer are fitted with the same wheels and tyres — snow chains for the driving-axle wheels, whose mudwings are removable, and a tool box is incorporated into the trailer mainframe to carry basic tools, engine oil and other general maintenance items. Reversing lights are fitted to both the tractive unit and trailer.

Recently Redbridge has set up a company, Redbridge GmbH in Frankfurt; the office is presently operating as a back-up to the English office, finding loads for the UK and elsewhere.

Redbridge is one of the fortunate companies to have a Community haulage permit and uses it to the full. Whichever vehicle is using the permit is normally engaged abroad; carrying the traffic for which the best rate can be obtained. Mr Harris told me that he always has more loads than he has permits to carry. To spread the use of permits he tries to send cargoes through Belgium and Holland and to Scandinavia, where permits are not required. This all demands careful planning, if one is not to be left without permits for the three months before a fresh allocation is due.

But then, as I hope I've indicated, success in international work depends on good planning — by drivers as well as by managers and traffic staff.