ONE MAN AND HIS UNIMOG

Page 66

Page 67

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

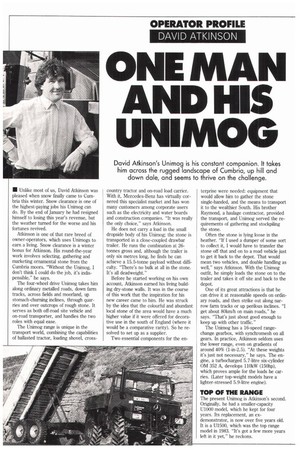

David Atkinson's Unimog is his constant companion. It takes him across the rugged landscape of Cumbria, up hill and down dale, and seems to thrive on the challenge.

• Unlike most of us, David Atkinson was pleased when snow finally came to Cumbria this winter. Snow clearance is one of the highest-paying jobs his Unimog can do. By the end of January he had resigned himself to losing this year's revenue, but the weather turned for the worse and his fortunes revived.

Atkinson is one of that rare breed of owner-operators, which uses Unimogs to earn a living. Snow clearance is a winter bonus for Atkinson. His round-the-year work involves selecting, gathering and marketing ornamental stone from the Cumbria moors. "Without the Unimog, I don't think I could do the job, it's indispensible," he says.

The four-wheel drive Unimog takes him along ordinary metalled roads, down farm tracks, across fields and moorland, up stomach-churning inclines, through quarries and over outcrops of rough stone. It serves as both off-road site vehicle and on-road transporter, and handles the two roles with equal ease.

The Unimog range is unique in the transport world, combining the capabilities of ballasted tractor, loading shovel, cross country tractor and on-road load carrier. With it, Mercedes-Benz has virtually cornered this specialist market and has won many customers among corporate users such as the electricity and water boards and construction companies. "It was really the only choice," says Atkinson.

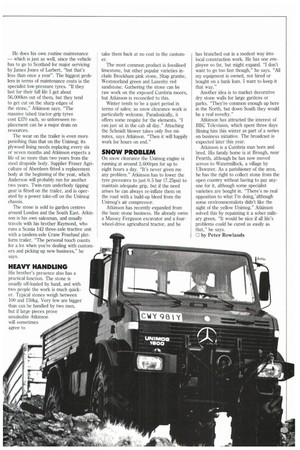

He does not carry a load in the small dropside body of his Unimog; the stone is transported in a close-coupled drawbar trailer. He runs the combination at 26tonnes gross and, although the trailer is only six metres long, he finds he can achieve a 15.5-tonne payload without difficulty. "There's no bulk at all in the stone. It's all deadweight."

Before he started working on his own account, Atkinson earned his living building dry-stone walls. It was in the course of this work that the inspiration for his new career came to him. He was struck by the idea that the colourful and abundant local stone of the area would have a much higher value if it were offered for decorative use in the south of England (where it would be a comparative rarity). So he resolved to set up as a supplier.

Two essential components for the en terprise were needed: equipment that would allow him to gather the stone single-handed, and the means to transport it to the wealthier South. His brother Raymond, a haulage contractor, provided the transport, and Unimog served the requirements of gathering and stockpiling the stone.

Often the stone is lying loose in the heather. "If I used a dumper of some sort to collect it, I would have to transfer the stone off that and on to a road vehicle just to get it back to the depot. That would mean two vehicles, and double handling as well," says Atkinson. With the Unimog outfit, he simply loads the stone on to the trailer and takes it off site and back to the depot.

One of its great attractions is that he can drive it at reasonable speeds on ordinary roads, and then strike out along narrow farm tracks or up perilous inclines. "I get about 80km/h on main roads," he says. "That's just about good enough to keep up with other traffic."

The Unimog has a 16-speed rangechange gearbox, with synchromesh on all gears. In practice, Atkinson seldom uses the lower range, even on gradients of around 40% (1-in-2.5). "At these weights it's just not necessary," he says. The engine, a turbocharged 5.7-litre six-cylinder OM 352 A, develops 110kW (150hp), which proves ample for the loads he carries. (Later top-weight models have a lighter-stressed 5.9-litre engine).

TOP OF THE RANGE

The present Unimog is Atkinson's second. Originally, he had a smaller-capacity U1000 model, which he kept for four years. Its replacement, an exdemonstrator, is now over five years old. It is a U1500, which was the top range model in 1983. "It's got a few more years left in it yet," he reckons. He does his own routine maintenance — which is just as well, since the vehicle has to go to Scotland for major servicing by James Jones of Larbert, "but that's less than once a year". The biggest problem in terms of maintenance costs is the specialist low-pressure tyres. "If they last for their full life I get about 56,000km out of them, but they tend to get cut on the sharp edges of the stone," Atkinson says. "The massive tubed tractor-grip tyres cost £370 each, so unforeseen replacement can be a major drain on resources.

The wear on the trailer is even more punishing than that on the Unimog; its plywood lining needs replacing every six or seven months and Atkinson expects a life of no more than two years from the steel dropside body. Supplier Fraser Agriculture of Aberdeen fitted a replacement body at the beginning of the year, which Anderson will probably run for another two years. Twin-ram underbody tipping gear is fitted on the trailer, and is operated by a power take-off on the Unimog chassis.

The stone is sold to garden centres around London and the South East. Atkinson is his own salesman, and usually travels with his brother Raymond, who runs a Scania 142 three-axle tractive unit with a tandem-axle Crane Fruehauf platform trailer. "The personal touch counts for a lot when you're dealing with customers and picking up new business," he says,

HEAVY HANDLING

His brother's presence also has a practical function, The stone is usually off-loaded by hand, and with two people the work is much quicker. Typical stones weigh between 100 and 150kg. Very few are bigger than can be handled by two men, but if large pieces prove unsaleable Atkinson will sometimes agree to take them back at no cost to the customer.

The most common product is fossilised limestone, but other popular varieties include Brockham pink stone, Shap granite, Westmorland green and Lazenby red sandstone. Gathering the stone can be raw work on the exposed Cumbria moors, but Atkinson is reconciled to this.

Winter tends to be a quiet period in terms of sales; so snow clearance work is particularly welcome. Paradoxically, it offers some respite for the elements. "I can just sit in the cab all day." Attaching the Schmidt blower takes only five minutes, says Atkinson. "Then it will happily work for hours on end."

SNOW PROBLEM

On snow clearance the Unimog engine is running at around 2,600rpm for up to eight hours a day. "It's never given me any problem." Atkinson has to lower the tyre pressures to just 0.5 bar (7.25psi) to maintain adequate grip, but if the need arises he can always re-inflate them on the road with a build-up bleed from the Unimog's air compressor.

Atkinson has recently expanded from the basic stone business. He already owns a Massey Ferguson excavator and a fourwheel-drive agricultural tractor, and he has branched out in a modest way into local construction work. He has one employee so far, but might expand. "I don't want to go too fast though," he says. "All my equipment is owned, not hired or bought on a bank loan. I want to keep it that way."

Another idea is to market decorative dry stone walls for large gardens or parks. "They're common enough up here in the North, but down South they would be a real novelty."

Atkinson has attracted the interest of BBC Television, which spent three days filming him this winter as part of a series on business initiative. The broadcast is expected later this year.

Atkinson is a Cumbria man born and bred. His family home is at Brough, near Penrith, although he has now moved across to Watermillock, a village by Ullswater. As a parishioner of the area, he has the right to collect stone from the open country without having to pay anyone for it, although some specialist varieties are bought in. "There's no real opposition to what I'm doing, although some environmentalists didn't like the sight of the yellow Unimog." Atkinson solved this by repainting it a sober military green. "It would be nice if all life's problems could be cured as easily as that," he says.

1:1 by Peter Rowlands