ROAD accidents in Great Britain in 1968 cost the country

Page 74

Page 75

Page 76

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

an estimated £23m. Some 420,000 vehicles of all types were involved, approximately 65,000 of them goods vehicles. These are staggering figures, and more so when one realizes that they apply only to accidents in which there was personal injury. No official figures are available which include damage to vehicles or property only, but it is not difficult to imagine that any such statistics would surely be of astronomical proportions.

The cost to industry and commerce of accidents involving goods vehicles in terms of repairs and loss of time off the road is, in these days of high costs, something which can be ill afforded and any efforts that are made to reduce this burden are extremely laudable.

The activities of RoSPA and Bosco, and the CM-sponsored Lorry Driver of the Year competition are major contributions towards increased road safety with commercial vehicles. But in addition to these, many companies consider the situation seriously enough to organize and sponsor their own competitions.

One such company which runs its own competition and also takes part in the RoSPA award scheme is Bowyers (Wiltshire) Ltd., famous for its sausages and pies. The nature of these highly perishable products makes it essential for them to be delivered with all possible speed. Delays due to accidents or mechanical breakdown are something which Bowyers takes every possible step to avoid. They cost money, they impair the quality of the product and as a result of this the company image is placed in jeopardy.

This image is very important to Bowyers in these times of severe competition in the trade; its fame dates back a long way—over 160 years.

Bowyers' transport operation is based on six nightly trunk services (Sunday to Friday) from the three manufacturing units, Trowbridge (Wilts), Plymouth and Liverpool to 63 sub-depots. From these sub-depots 350 light sales-vans with salesmen-drivers distribute the manufactured meat products to retail outlets throughout the country.

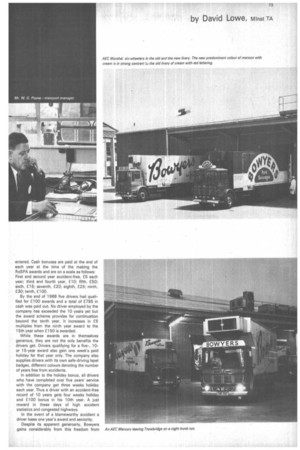

The trunk fleet-47-strong—consists of Ford D700 and D1000 rigids and AEC Mercury, Marshal and Mammoth Major rigids and four Mandator tractive unit and semitrailer outfits.

The majority of the trunk vehicle fleet operates from Trowbridge, the company headquarters, and from here vehicles travel as far as Stoke-on-Trent in the north and Torquay in the south—they also cover Wales, the Midlands and Home Counties.

All trunk deliveries have to be completed by 5 a.m. to ensure that the retail delivery vehicles can be loaded and sent away on time.

It is in the trunk vehicle fleet that I was most interested to discover whether elaborate safe driving schemes and accident-free bonuses had any effect on the standard of driving. The answer in Bowyers' case is a categorical YES. It has statistics which show that during the last 12 months the trunk fleet covered 2m miles and was involved in only three blameworthy accidents. Considering that most of this mileage was covered at night, this is a remarkable record. • In addition to this low accident record only 47 hours' running time out of 120,000 hours has been lost due to breakdowns or inclement weather. The breakdown record for the fleet works out at one per 75,000 miles. And just to stretch the statistics a little further, 22,220 depot deliveries were made in the 12 months; this represented some 21rn loaded plastic trays being delivered and brought back empty.

I set out to discover what methods were employed to achieve such a creditable record of freedom from accidents and breakdowns in the hope that I might learn some magical formula to pass on to others whose records on either account are not so clean. Unfortunately there is no such formula, only a generous accident-free award scheme, which reflects the savings to the company from the heavy costs of accidents, and a sound inspection and repair system which is rigidly adhered to.

Drivers, like most people, are usually only interested in a scheme if they are going to get something (particularly money) out of it. Bowyers' drivers are no exception and their interest and enthusiasm for the safe driving scheme is kept at a high pitch by the awards which are available.

The award scheme is based on the RoSPA competition for which all company drivers are entered. Cash bonuses are paid at the end of each year at the time of the making the RoSPA awards and are on a scale as follows: First and second year accident-free, £5 each year; third and fourth year, £10; fifth, £50; sixth, E15; seventh, £20: eighth, £25; ninth, £30; tenth, £100.

By the end of 1968 five drivers had qualified for £100 awards and a total of £795 in cash was paid out. No driver employed by the company has exceeded the 10 years yet but the award scheme provides for continuation beyond the tenth year. It increases in £5 multiples from the ninth year award to the 15th year when £150 is awarded.

While these awards are in themselves generous, they are not the only benefits the drivers get. Drivers qualifying for a five-, 10or 15-year award also gain one week's paid holiday for that year only. The company also supplies drivers with its own safe-driving lapel badges, different colours denoting the number of years free from accidents.

In addition to the holiday bonus, all drivers who have completed over five years' service with the company get three weeks holiday each year. Thus a driver with an accident-free record of 10 years gets four weeks holiday and £100 bonus in his 10th year. A just reward in these days of high accident statistics arid congested highways.

In the event of a blameworthy accident a driver loses one year's award and seniority.

Despite its apparent generosity, Bowyers

gains considerably from this freedom from An AEC Mercury leaving Trowbridge on a night trunk run.

accidents; while the costs of accidents are intangible it is certain that only very few would incur costs in excess of the amount of the bonuses paid.

No special scheme of driver training is employed but careful selection in the first instance has a great bearing on the quality of the driving standard. All new drivers are given an extensive driving test by the fleet engineer and employed on one month's probation as a day shunter; from that position over a period of six months they complete a spell as night shunter, under less supervision, spare driver and eventually they can go on trunk runs.

The period spent shunting and as spare driver gives new drivers experience of the products handled, the vehicles and paperwork under supervision during daylight hours. There are, however, two additional requirements before drivers are allowed on the trunk runs: they must be aged 30 and have had five years' experience of driving heavy commercial vehicles.

The statistics of mileages, hours operated and breakdowns are taken from driver reports of each trunk run. Details of any delay are shown with the cause and the action taken and the total time of the delay. In the event of an accident, details are recorded and an accident report filled in. When it gets near to the time for making application for the RoSPA awards the accident reports are all examined by Mr. W. G. Payne, the transport manager, the shop steward and a representative of the driving staff to ascertain the awards to be claimed. A dinner is held every year for staff at which the awards are presented.

Mr. Payne is enthusiastic about the high standard of his drivers but he also sets a good example by his membership of the Institute of Advanced Motorists; he is also a Knight of the Road and has an accident-free record of 25 years.

Vehicle maintenance to achieve the low breakdown record consists of a straightforward system of inspections and lubrication services at set intervals. Ldbrication services are carried out every two weeks, oil changes and inspections every four weeks and more extensive inspections and repair programmes at three-, sixand 12-monthly intervals.

Strict adherence to these maintenance schedules is the secret of the success coupled with the conscientious attitude of the maintenance staff who carry out the work (Mr. Payne calls them his backroom boys). A system of unit replacement at fixed intervals is followed, particularly with perishable parts such as fan belts and cooling systems' hoses. To have a vehicle standing by the roadside because a fan belt has broken or a hose burst is not one of Mr. Payne's ideals. The cost of these items is so low as to make it economical to change them rather than take a risk. Hydraulic brake and clutch parts are also carefully inspected and replaced at regular intervals.

Big extension planned

A large maintenance staff is not employed, neither is the workshop a palace of perfection and certainly excessive spare vehicles are not available to enable vehicles to be off the road frequently or for long periods. A big extension is planned for the workshops next year but in the meantime repairs and maintenance are carried out by a small team dedicated to keeping the wheels turning. Careful planning is the essence of whole distribution system from the trunk timings to maintenance schedules, and Mr. Payne thinks that for the type of product the system is second to none and the spirit of the drivers depends on a good maintenance staff backing them up.

I asked Mr. Payne about his MoT testing experience. He has had 22 vehicles put through the test, and all passed except two which were cleared the same day, one of which had new brake linings which only needed bedding in by driving round the block a few times. And there had been no special prepara

tion, I was told. Vehicles were not available for time off except for pre-planned service periods, and the MoT test was booked to coincide with these.

I mentioned Bowyers' image earlier—its importance is reflected in the high state of cleanliness of the vehicles internally and ex ternally. Again, because of the nature of the product, internal cleanliness is of paramount importance and vehicles are therefore steam-cleaned internally every day and washed externally twice a week. A new ultrasonic vehicle washer is to be delivered soon which will enable the frequency of external washings to be stepped up.

Many of Bowyers' vehicles are now to be seen in their new livery which brings the image of the company up to date. Also a number of refrigerated vehicles in a blue and white livery have been put into service recently for carrying frozen foods.

All vehicles are repaired and repainted every two years by Sawyers' own body repair and painting staff and Bowyers has its own signwriter. I asked Mr. Payne to analyse the success of the system and pinpoint the one factor that contributed most to it. He assured me that it all revolved round the standard of drivers. The company made every effort to reward drivers justly and treat them with some importance, in return obtaining the previously mentioned results of which the firm is proud. The drivers are happy, too, and not surprisingly Bowyers has no difficulty in recruiting good drivers from its waiting lists.

This, then, is the system of one fleet operator who realizes that breakdowns and ac cidents are too expensive to tolerate and has set about finding a way of diminishing both. It is not a revolutionary system and many oper ators who read this may well have records to equal or even surpass that of Bowyers. However, the pointer is there to be considered by those who wish to achieve the same objects but have yet to discover a method of doing so.