THE ELECTRIC COMMERCIAL VEHICLE.

Page 10

Page 11

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Where it can be Efficiently Employed; its Advantages and its Limitations. By Chief Engineer.'

THE PROMINENT position which the electric commercial vehicle is gradually assuming for short distance transport in towns, both for commerce and the various sanitary and other municipal services, is a. practical proof that this type of machine has a useful, if somewhat rigidly defined, field of employment. At the same time, there is a multitude of jobs, within its capabilities, eminently suited to it.

In the main, the electric differs from the petrol or steam driven wagon in one very prominent essential, namely, its limited range of action. If a petrol or steam wagon is employed distance is no obstacle to its use, as it is all a question of taking enough coal or petrol on board, or picking it up en route. Further, hills present no great difficulty, and only affect the amount of fuel used and the time taken for a journey. Now, the electric vehicle is in an altogether different category. The distance is limited entirely by the capacity of thc storage+ battery employed, and, on reasonably level good town roads, the range per charge may be taken approximately as follows:— 15 cwt. vehicle, 45 to 50 miles.

30 cwt. vehicle, 45 miles.

2i ton vehicle', 40 miles.

31ton vehicle, 35 miles. , If the district is hilly, these mileages per charge will be very greatly reduced, and may quite conceivably be as tow as 10 miles Per charge i n particularly hilly towns, or where the surfaces of the roads are not of the best. Then, further, the weather has a certain effect on the mileage, and the distance travelled in summer will be found to exceed the winter mileage per charge by a considerable amount. This limitation of the daily mileage may be to a certain extent modified by one or a combination of the following methods. '

(1) When the owner , has his o w ri charging plant, it should be arranged so that ci6

the battery can be given a " boosting " charge while the -wagon is being loaded at any time during the day, or at the mid-day meal hour.

(2) Interchangeable batteries may be employed. In connection with the first method it should be explained that a " boosting " charge is a charge given for a. sh,ort period, but at a high rate. The intensity of a boosting charge is dependent upon the condition of the battery. and the time available. The makers of the various batteries are always willing to supply the necessary information. In order that the second method may be adopted, makers of these vehicles are arranging to fit the storage batteries in small trucks which are carried on rails fixed to the floor of the battery chamber. The doors of the battery chamber are often hinged, so that when they are open they form stages having rails corresponding to the rails on the floor of the chamber proper. The little trucks containing the batteries can then be run on to these platforms for inspection, and, further' can be wheeled off the platforms on to a specially designed truck having also rails corre .sponding to those in the battery chamber. The discharged battery can then be wheeled away, and a. fully charged one brought back to take its place. By adopting such 'a scheme, a very considerable mileage can be obtained from the vehicle, with the single reservation that its work must always be arranged so that it is within reach of its headquarters when the battery is nearly discharged, otherwise its fate will 'be that of having to be ignominiously toived home.

In order to increase the sphere of usefulness of these vehicles, there are several schemes for battery service companies under consideration in various parts of the country, and at least one, namely, in the Newcastleon-Tyne district, has actually commenced operations. The general scheme upon which these companies will work is that of letting out • on hire storage batteries at a certain rate per mile, , they being responsible for the upkeep and charging. Where such a service company is in operation the owner of a vehicle could, at any time, take it to, one of the service company's depots and have his discharged battery removed, and a fully charged one substituted. Such companies do not, as a rule, prow pose to limit themselves to the hire of batteries only, but -would com`bine with this the purchase and sale of electrics, either outright or on a hire purchase • basis, also they would undertake the supply of tyres • and other spares. From the above it will be seen that the present very limited daily. mileage is being overcome to a certain extent. At the same time the work for which the electric is most suitable does not call for a big daily .run. It is essentially a vehicle for town and short distance work, especially where deliveries a n d collections a r e numerous, which entail much stopping. F o r such work, whatever the vehicle employed, it has been found, over and over again, that it is difficult to reach an aver age of 2'5 miles The Garrett 2-ir on electric vehic per, day, which is constructe well within the limits of the single battery charge, except in very hilly towns. In fact, the electric is the competitor of the horse, and is rarely in competition with petrol and steam vehicles. It is a pity that this fact was not more fully recognized in the past. The electric vehicle suffered greatly awing to being put forward as a rival to petrol and steam vehicles, and was recommended for work for which it was totally unfitted. In its own sphere it is ideal, but out of it it has been called other things.

The speed of an electric is moderate, as its pars ticular sphere of usefulness does not call for great speed. The. following table gives the average speeds of different sizes on reasonable town roads.

175 cwt. wagon, 16 m.p.h. 30 cwt. wagon, 14 m.p.h. 21 ton wagon, 12 m.p.h.. ton wagon, 10 m.p.h.

They have the disadvantage of being very slow on bills. A vehicle capable of maintaining an average speed of 10 m.p.h. on the level would probably only run at about 21 m.p.h. to 3 m.p.h. when climbing a gradient of 1 in 8_ However, they have many advantages for their particular work, amongst which may be mentioned:— (1) Ease of control. Cleanliness.

(3) Easy to learn to drive.

(4) No standby lasses. (5) Convenient in traffic.

(6) Excellent view of the road.

(7) Low cost of stores.

(8) Low upkeep charges.

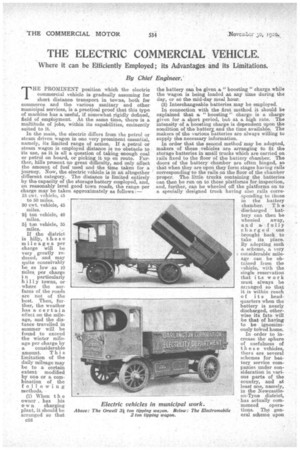

In general design battery vehicles are arranged in 'two styles. In one the motor is slung on the chassis and the hind wheels driven from it by chains through countershaft, or direct by worm gearing. In the latter case the axle is a live one. By this arrange ment the motor and a considerable portion of the gearing is sprung w-eight and is, therefore, to some extent, relieved from road shocks. This type of vehicle is well represented by the G.V., the Garrett, and the larger sizes of the Orwell. Under the second heading come those vehicles in which the motor-forms part of the front or rear axles, driving either the front or rear wheels through special gearing, consequently in such an arrangement the whole of the power unit and gearing is unsprung, and all road shocks are transmitted to these parts without any relief from the springs. Such vehicles are represented by the Electroinobile and smaller sizes of the Orwell, built by Ransonies, Sims and Jefferies, Ltd., of Ips-wich, and certain American designs. Which type will become the more general in this country will depend on the results after a few more years of use. They have been employed for so short a time in e.ngland that one can only eoniec ture. ',12he latter type appears in most cases to possess the great advantage of. simplicity, but what the effect of road shocks will be upon. the motor a ri d gearing, . . only experience le with a run-back tipping body, extending over a.

d in steel. considerable period will tell. It scarcely seems an ideal condition for a motor commutator to run under, and, if the writer may be permitted a personal opinion, he would be inclined to consider that the final type will probably be on the general lines of the first type, that is, with as much of the mechanism sprung as possible, and, further, with a fixed rear axle.

In deciding upon an electric vehicle, and in examining the designs certain points niust be kept clearly in mind. As already mentioned, the mileage is limited by • the battery capacity. It, therefore, follows that it is very essential to keep dawn the weight of the vehicle, to the lowest limit consistent with safety. Also all driving mechanism should be of the best, with a view to reducing friction, and the moving of unnecessary weight, so that as great a percentage as possible of the battery capacity may be utilized in transporting paying load. Every bearing. throughout the vehicle should be of the ball or high-class roller type, and wherever possible chains and other gearing should 'run in an oil -bath. At present far too many chains are running exposed, with the result that they collect dirt, requirethequent greasing, and, even then' cause undue wear to the sprockets and chain wheels. When a. chain is completely enclosed and runs in an oil bath its life is considerably extended, besides providing a more silent transmission and saying' considerable lubricant. ' There are two distinct types of storage battery employed, namely (1) The nickel and steel. (2) The .lead. The former class is represented principally by the Edison accumulator, and the latter by the Ironclad Exide, which is manufactured by the Chloride Electrical Storage Co., Ltd. Next week I will deal with the relative advantages of these two types of storage batteries, and also with the design of certain representative types of vehicles on which they are employed. (To be continued.)