The Emission of "Visible Vapour. /

Page 6

Page 7

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

How Users of Steam Wagons can be Safeguarded against Trouble in Cold Weather.

The fittings that are commonly provided on steam wNgons, to prevent the formation of smoke, or, in other words, the steps that are taken to make the vehicle comply with the definition " so constructed that no smoke . . . is emitted therefrom, except from any temporary or accidental cause," were explained in last week's issue of " THE COMMERCIAL MOTOR." It is purposed to deal, now, with the equally important question of visible vapour, which is included in the same definition clause. Some means must be ,adopted to dispose of the steam after it has done its work in the cylinders. The exhaust steam is, therefore, turned either into a condenser or up the funnel; in the latter case, the up-draught produces a vacuum in the lower portion of the smoke-box, and causes a rush of air through the fire to fill that vacuum, this induced draught fulfilling a very important function with a coal or coke fire. The quanttty of steam produced by a boiler is proportional to the heat given off by the fire, which again varies with the amount of air drawn through it. It will be seen that the amount of steam generated becomes proportional to the amount of exhaust steam discharged up the funnel, whilst it is only pro_ duced practically as fast as it is used. The Chelmsford steam omnibuses now at work on several services, and steam cars of the White and Turner-Miesse types, employ liquid fuel in special burners. These burners make their own draught and, therefore, the steam can be disposed of by condensing it to water, and using the water over again.

There is no legal necessity to prevent "visible vapour" in the case of traction engines and steam rollers. The usual practice with these "locomotives "is to lead the exhaust into the base of the funnel, and to turn it upwards through a jet, but most makers of steam wagons take extra precautions to ensure that the exhaust will be rendered invisible. The exhaust steam from an engine on a hot day will probably disperse invisibly, but, on a cold, damp day, much of it will be condensed directly it leaves the funnel, and take the shape of dense clouds of visible vapour. It is unsettled whether the Law can take notice of weather vagaries, and it is expedient to take steps to render the exhaust invisible at all times, if possible; this is why so many makers are at special pains to dry the exhaust steam. It is first passed through a trap, or separator, and any water that may be present as liquid particles is intercepted. The modern steam tractor is built on traction engine lines, and the exhaust pipe of one is clearly shown in Fig. 1. Similarly, Fig. 2 shows the exhaust jet on a Thornycroft water tube boiler. On the Thornycroft and Yorkshire steam wagons the trapped water is drained into the ashpan, where it serves to prevent the ashes from being blown about or from falling on the road when hot, but further precautions are not adopted in the Thornycroft system. Other makers have additional fittings to heat the exhaust steam before discharging it into the atmosphere.

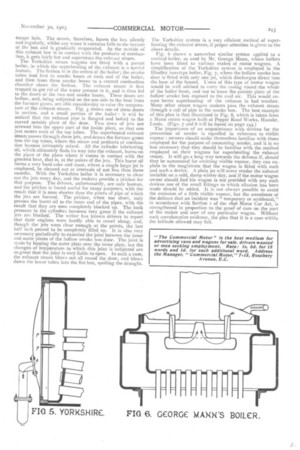

The plan adopted on the Lifu wagon of tSog is shown in Fig. 3, which is a view looking down the funnel. The exhaust from the engine passes into an oval ring, from which it is discharged through a number of small holes. It is thus effectually split up and intimately mixed with the furnace gases. On the Foden steam wagon a locomotive type of boiler is employed, and the cylinders are mounted on the top of the boiler as in traction engine practice. The exhaust is led from the cylinders to the. smoke box, and is passed into a circular cast-iron box secured across the upper part of the smoke box (Fig. 4). The further end of the exhaust box is flanged, and a plate, which is extended at the lower end, and bent to form a bracket for bolting to the inside of the smoke box, effectually closes it.

In the upper portion of this box is a small hole through which the steam ultimately finds its way up the funnel. The natural effect of turning the exhaust into such a box is to destroy any noise which it might cause, because each puff is directed towards the end of the box and not towards the escape hole. The steam, therefore, leaves the box silently and regularly, whilst any water it contains falls to the bottom of the box and is gradually evaporated. As the outside of this exhaust box is in contact with the products of combustion, it gets fairly hot and superheats the exhnust steam. The Yorkshire steam wagons are fitted with a patent boiler, in which the superheating of the exhaust is a special feature. The firebox is in the centre of the boiler; the smoke tubes lead first to smoke boxes at each end of the boiler, and then from these smoke boxes to a central combustion chamber above the firebox. The exhaust steam is first trapped to get rid of the water present in it, and is then led to the doors of the two end smoke boxes. These doors are hollow, and, being subjected on the one side to the heat from the furnace gases, are able considerably to raise the tempera. ture of the exhaust steam. Fig. 5 shows one of these doors in section, and a small portion of the boiler: it will be noticed that the exhaust pipe is flanged and bolted to the curved outside plate of the door. Two rows of jets are screwed into the upper part of the inside plate, so that one just enters each of the top tubes. The superheated exhaust steam passes through these jets, and draws the furnace gases into the top tubes, where the steam and products of combustion become intimately mixed. All the cylinder lubricating oil, which ultimately finds its way into the exhaust, burns on the pipes at the place where it comes in contact with the greatest heat, that is, at the points of the jets. This burnt oil forms a very hard cake and must, where a single large jet is employed, be cleaned out at intervals of not less than three months. With the Yorkshire boiler it is necessary to clear out the jets every day, and the makers provide a pricker for that purpose. The drivers, unfortunately, are only human, and the pricker is found useful for many purposes, with the result that it is soon shorter than the pieces of pipe of which the jets are formed. The pricker, when too short, only presses the burnt oil to the inner end of the pipes, with the result that they are soon completely blocked up. The back eressure in the cylinders becomes very great if the exhaust Jets are blocked. The writer has known drivers to report that their engines were hardly able to crawl along, and, though the jets were clear enough at the points, the last half inch proved to be completely filled up. It is also very necessary periodically to examine the joint between the inner and outer plates of the hollow smoke box door. The joint is made by lapping the outer plate over the inner plate, but the changes of temperature to which this joint is subjected are so great that the joint is very liable to open. In such a case, the exhaust steam blows out all round the door, and blows down the lower tubes into the fire box, spoiling the draught.

The Yorkshire system is a very efficient method of superheating the exhaust steam, if proper attention is given to the above details.

Fig. 6 shows a somewhat similar system applied to a vertical boiler, as used by Mr. George Mann, whose boilers have been fitted to various makes of motor wagons. A simplification of the Yorkshire system is employed in the Ilindley loco-type boiler, Fig. 7, where the hollow smoke box door is fitted with only one jet, which discharges direct into the base of the funnel. Users of this type of motor wagon would be well advised to carry the casing round the whole of the boiler front, and not to leave the outside plate of the hollow smoke box exposed to the cold air. This would ensure better superheating of the exhaust in bad weather. Many other steam wagon makers pass the exhaust steam through a coil of pipe in the smoke box. The best example of this plan is that illustrated in Fig. 8, which is taken from a Mann steam wagon built at Pepper Road Works, Hunslet, Leeds. (Figs. 7 and 8 will be found on page 245.) The importance of an acquaintance with devices for the prevention of smoke is equalled in reference to visible vapour owners should make themselves familiar with those employed for the purpose of consuming smoke, and it is no less necessary that they should be familiar with the method employed on their wagons for superheating the exhaust steam. It will go a long way towards the defence if, should they be summoned for emitting visible vapour, they can explain to the magistrate that the wagon is fitted with such and such a device. A plain jet will never render the exhaust invisible on a cold, damp winter day, and if the motor wagon owner should find his wagon is not provided with any such devices one of the small fittings to which allusion has been made should be added. It is not always possible to avoid the emission of a little visible vapour, but the soundness of the defence that an incident was" temporary or accidental," in accordance with Section i of the 1896 Motor Car Act, is strengthened in proportion to the proof of care on the part of the maker and user of any particular wagon. Without such corroborative evidence, the plea that it is a case within the latitude allowed may fail.