Metropolitan is logical development of single -decker

Page 46

Page 47

Page 54

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

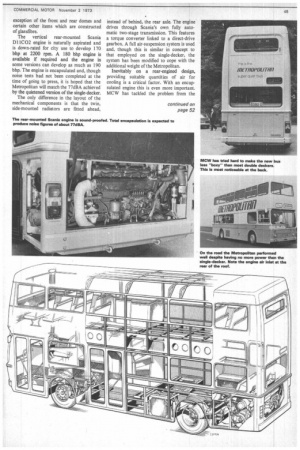

ANNOUNCED today is Metro-Cammell Weymaim's integral double-decker, called the Metropolitan, which is a logical development of the Metro-Scania singledecker. Essentially, all the major running units are similar to those used in the single-decker, of which there are now more than 150 on British roads. The basic construction method used in the body is the same, too, though the new model is much more than a single-decker with an extra deck tacked on top.

Initiative for the Metropolitan project came in 1967, when a market survey conducted by MCW showed that the demand for double-deckers had suddenly intensified. The fact that the single-decker was then at an advanced stage of development enabled the company to switch over to deckers much more quickly than its competitors.

British content The Metropolitan, of course, is rearengined and fully integral. The running units engine, transmission, axles and steering gear — are all shipped direct from Scania in Sweden to MCW's Birmingham factory. With the vehicle completed, however, British content accounts for more than 70 per cent of the total.

Perhaps the major change in design from the single-decker — emphasizing that this is a completely new vehicle — is that the pillar spacing is different. The Metropolitan has 5ft 44-in, bays compared with the single-deckers 4ft lin. significantly, those big bays are the same size as those used in MCW's standard double-deck bodies. Load-bearing sections of the body are in steel which is phosphate primed and bitumen coated up to lower saloon waist level. Antidielectric paint is applied to areas where steel structural assemblies and aluminium panels join.

The basic structure of the bus — which is self-supporting — is all-welded, jig-built and consists of rolled or folded steel sections. Below the lower saloon window line is a steel truss panel, 1 lin. deep and 0.05in. thick. This bears much of the body's stress together with forming a collision protection.

However, the body's main load-bearing member is situated at the lower saloon cantrail level. This is a channel section lft 6in. deep and 0.08in. thick. Its top flange forms the upper saloon bodyside seat fixing. Essentially this member takes much of the load borne by the roof in the single-deck version. Additional reinforcement is incorporated over the doors. The main side pillars extend from sill to upper saloon cantrails where they connect with the roof supports. Cross-members under floor level complete the typical integral hoop structure. External panels are in aluminium with the exception of the front and rear domes and certain other items which are constructed of glassfibre.

The vertical rear-mounted Scania Dl 1CO2 engine is naturally aspirated and is down-rated for city use to develop 170 bhp at 2200 rpm. A 180 bhp engine is available if required and the engine in some versions can develop as much as 190 bhp. The engine is encapsulated and, though noise tests had not been completed at the time of going to press, it is hoped that the Metropolitan will match the 77dBA achieved by the quietened version of the single-decker.

The only difference in the layout of the mechanical components is that the twin, side-mounted radiators are fitted ahead, instead of behind, the rear axle. The engine' drives through Scania's own fully automatic two-stage transmission. This features a torque converter linked to a direct-drive gearbox. A full air-suspension system is used and, though this is similar in concept to that employed on the single-decker, the system has been modified to cope with the additional weight of the Metropolitan.

Inevitably on a rear-engined design, providing suitable quantities of air for cooling is a critical factor. With an encapsulated engine this is even more important. MCW has tackled the problem from the Specialized operators Much of the criticism of the Board's new scheme comes from specialized operators, especially those whose vehicles frequently carry inflammable or otherwise dangerous traffic. For obvious reasons, they normally take on only fully qualified and experienced drivers. They adhere more than most to the school of thought which maintains that the requirements of the hgv test are the least among the necessary qualifications.

Operators in general are not greatly worried by the new arrangement, especially following assurances that it will not be applied too rigidly. Training of new recruits is an accepted obligation. Hauliers share the Board's much more serious apprehension about the continual seepage of trained drivers into other industries and into employment agencies.

Ultimately Government help may be needed. There are channels outside the scbpe of the RTITB through which the cost of training drivers can be met. Either these channels must be enlarged, or a way must be found of obtaining funds for driver training from the many other interests which at the moment are free of any obligation to

train or to pay. by Janus