Hutchings prepares for a leap in the dark

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

From June 1 the responsibilities of licensing authorities will be even greater. They will have to handle environmental objections with new powers as vague as they are far reaching. Jack Semple talks to the man in the hot seat in North West

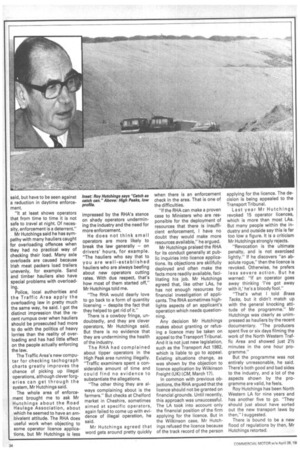

VISITORS to Arkwright House, Manchester, the home of the North Western Traffic Area, will notice that time seems to have stood still for decades.

Dull china tiles on the staircase, highly polished thin brass handrails and antedeluvian "way out" lamps in each corridor are matched for atmosphere by the silence of a monastery.

Licensing Authority Roy Hutchings' expansive office still boasts a pre-motorway road map, but some concessions have been made to the passing of the years — for example, bright relatively new chairs (doubtless bought in the time of a spendthrift Labour Government).

Appearances, of course, can be deceptive. The institution of LAs may be 50 years old, but transport's regional governors today have to be right up to date with changes in the law and the industry.

This point is well demonstrated by changes coming into effect from June 1, which will give councils and local residents the right to object to the granting of an operator licence because of the environmental impact of the operation.

The change is being made under the Transport Act 1982 and is one of the biggest innovations in road freight transport for -many years.

Licensing Authorities will have the unenviable task of deciding in the first place how to implement the new rules, many of which are as precise as the length of a piece of string. So they seemed like a good place to start when I spoke to Mr Hutchings two weeks ago.

Hauliers hoping that the confusion surrounding the new regulations has been sorted out just a month before their introduction will be disappointed.

"We just don't know what is going to happen after June 1," Mr Hutchings told me. "I can't foresee all the things which are going to be raised. I've got to suck it and see, I really don't know what I'm going to do.

"Each case has to be decided on its own. I expect a lot of the early cases will go to appeal (to the Transport Tribunal in London)."

Mr Hutchings was able to give some pointers as to who he expected to be affected by the new rules and how they might be applied.. For example, who is likely to object to licence applications?

In his annual report to the Transport Secretary, Mr Hutchings noted an increasing number of complaints from the public about lorry operators. Typically, these objectors are in towns rather than cities, he told me.

The most common complaints are about noise in the early morning or late at night, about lorries left outside premises all day or parked on streets overnight so that the driver could make an early start in the morning. All these points could be valid grounds for objecting to the granting of a licence.

Letters also complained about litter being blown from lorries parked at operating centres, and similar nuisance from coal, scrap and steel yards. These objections are now excluded from the regulations, having been dropped at an early stage.

Councils are likely to make full use of their new right to object, Mr Hutchings warned. Particularly, operators who have had opposition from local authorities in the past can expect trouble when their licence comes up for renewal.

Councils have often objected to licence applications in the past on environmental grounds, only to be told at public inquiry that they had no right in law to make the objection. It is unclear whether councils will lodge environmental objections through their planning department or treat them as a seperate issue, Mr Hutchings said.

Mr Hutchings said he is considering asking councils to make a special effort to represent residents who want to object to a licence application. "I would hope that in future where people feel aggrieved by the intrusion of an hgv operating depot, they would go through their councillor and seek to get the council to act on their behalf. Otherwise we'll get a lot of people objecting who do not know what it's about."

One clearly presented objection carries just as much weight as 30 or 40 angry residents, he said.

When an objection is raised, Mr Hutchings intends to go and see the problem for himself. He will hold a public inquiry locally, so that residents can attend easily. But he won't stand any nonsense from objectors, along the lines that planning inquiry inspectors have to suffer. "That's not on," he told me. The regulations allow him to rule out such objections as frivolous or vexatious.

"We don't want to sow seeds in anyone's mind that the public inquiries will be anything like planning inquiries," he said.

Small haulage firms will be the worst hit by the new environmental rules, Mr Hutchings suggested. These firms typically operated from a small yard or back garden. Small own-account operators are more likely to have larger premises.

Big fleets are unlikely to be as vulnerable to local objections. They tend to be in established depots on industrial sites.

Mr Hutchings would not be drawn on the level of environmental impact he would consider enough to refuse or impose conditions on a licence, or what would constitute a "material change". Only lorry parking conditions can be imposed if there has been no material change, under the regulations.

But he did suggest that only the effect of the material change could be taken into account at a public inquiry, not the environmental impact of the operation as a whole. This might have to be confirmed at the Transport Tribunal, he said.

I asked Mr Hutchings if he welcomed the added responsibility and power granted to LAs by the 1982 act. "No," he said. But he certainly was not too bothered by it. "Its another task." Certainly the extra work might well stretch resources, but Mr Hutchings said he has the option of appointing a second deputy LA, perhaps to cover Cumbria. (Deputy LA already covers the Liverpool area.) The vexed question of enforcement leaves Mr Hutchings similarly unperturbed. He and his department simply get on with doing the job as best they can with the resources available.

"Enforcement is there at the level of resource on the basis of catch as catch can. I don't want to be seen as bellyaching about lack of staff." He added: "I could certainly usefully employ more than I have now."

At present Mr Hutchings has 25 traffic examiners. In his 1983 report, a temporary addition of four more staff led to a "noticeable increase in enforcement activity.'

Operators fall into two distinct categories for the purposes of checking on maintenance, it appears. "New operators tend to need more surveillance than established operators. They are very often feeling their way."

New operators are often drivers who have been made redundant. They may have grandfather rights or have passed the Certificate of Professional Competence examination.

"Most do not do their own maintenance," Mr Hutchings said. They send him a letter of intent or in some cases a contract with a garage when applying for their licence.

Mr Hutchings said he regarded maintenance as particularly important. So virtually all operators' were checked in their first year of operation, usually in the first six months. Normally this takes the form of a personal visit by an enforcement officer.

More established operators are treated entirely differently, however. "Management by exception" was the way Mr Hutchings described the level of enforcement on their maintenance.

The situation is not as bad as it sounds, said Mr Hutchings. All operators' vehicles have to go through annual test, and vehicle examiners often get a feel for when an operator is not maintaining his lorries properly and further checking is needed. "They are very experienced," Mr Hutchings said.

Roadside enforcement has been stepped up in the North West, with the result that 50 per cent more lorries were weighed at spot-checks last year. This was due entirely to the gradual introduction of more weighbridges from two to five. There are now seven weighbridges in the area.

Night checks were introduced for the first time six months ago. A clear picture of their effect is not yet available, but Mr Hutchings seems less than wholly enthusiastic about them. They are "moderately successful," he said, but have to be seen against a reduction in daytime enforcement.

"It at least shows operators that from time to time it is not safe to travel at night. Of necessity, enforcement is a deterrent."

Mr Hutchings said he has sympathy with many hauliers caught for overloading offences when they had no practical way of checking their load. Many axle overloads are caused because Irish meat packers load trailers unevenly, for example. Sand and timber hauliers also have special problems with overloading.

Police, local authorities and the Traffic Area apply the overloading law in pretty much the same way, he said. I got the distinct impression that the recent rumpus over when hauliers should be prosecuted had more to do with the politics of heavy lorries than the reality of overloading and has had little effect on the people actually enforcing the law.

The Traffic Area's new computer for checking tachograph charts greatly improves the chance of picking up illegal operations, although clever forgeries can get through the system, Mr Hutchings said.

The whole area of enforcement brought me to ask Mr Hutchings about the Road Haulage Association, about which he seemed to have an am bivalent attitude. The RHA does useful work when objecting to some operator licence applications, but Mr Hutchings is less impressed by the RHA's stance on shady operators undermining the industry and the need for more enforcement.

He does not think small operators are more likely to break the law generally — on drivers' hours, for example. "The hauliers who say that to you are well-established hauliers who are always beefing about new operators cutting rates. With due respect, that's how most of them started off," Mr Hutchings told me.

"The RHA would dearly love to go back to a form of quantity licensing — despite the fact that they helped to get rid of it."

There is a cowboy fringe, undoubtedly, and they are clever operators, Mr Hutchings said. But there is no evidence that they are undermining the health of the industry.

The RHA had complained about tipper operators in the High Peak area running illegally. "Traffic examiners spent a considerable amount of time and could find no evidence to substantiate the allegations.

"The other thing they are always complaining about is the farmers." But checks at Chelford market in Cheshire, sometimes aimed at specific operators, again failed to come up with evidence of illegal operation, he said.

Mr Hutchings agreed that word gets around pretty quickly when there is an enforcement check in the area. That is one of the difficulties.

"If the RHA can make a proven case to Ministers who are responsible for the deployment of resources that there is insufficient enforcement, I have no doubt they would make more resources available," he argued.

Mr Hutchings praised the RHA for its conduct generally at public inquiries into licence applications. Its objections are skillfully deployed and often make the facts more readily available, facilitating his job. Mr Hutchings agreed that, like other LAS, he has not enough resources for financial investigation of applicants. The RHA sometimes highlights aspects of an applicant's operation which needs questionfling.

Any decision Mr Hutchings makes about granting or refusing a licence may be taken on appeal to the Transport Tribunal. And it is not just new legislation, such as the Transport Act 1982, which is liable to go to appeal. Existing situations change, as was shown by the objection to licence application by Wilkinson Freight (UK) (CM, March 17).

In common with previous objections, the RHA argued that the licence should not be granted on financial grounds. Until recently, this approach was unsuccessful. The LA took into account only the financial position of the firm applying for the licence. But in the Wilkinson case, Mr Hutchings refused the licence because of the track record of the person applying for the licence. The decision is being appealed to the Transport Tribunal.

Last year Mr Hutchings revoked 15 operator licences, which is more than most LAs. But many people within the industry and outside say this is far too low a figure. It is a criticism Mr Hutchings strongly rejects.

"Revocation is the ultimate penalty, and is not exercised lightly." If he discovers "an absolute rogue," then the licence is revoked. Otherwise, he prefers less severe action. But he warned: "If an operator goes away thinking 'I've got away with it,' he's a bloody fool."

"That's what I told Brass Tacks, but it didn't match up with the general knocking attitude of the programme." Mr Hutchings was clearly as unimpressed as hauliers by the recent documentary. "The producers spent five or six days filming the work of the North Western Traffic Area and showed just 21/2 minutes in the one hour programme."

But the programme was not entirely unreasonable, he said. There's both good and bad sides to the industry, and a lot of the aspects shown by the programme are valid, he feels.

Roy Hutchings has been North Western LA for nine years and has another five to go. "They should just about have sorted out the new transport laws by then," I suggested.

There is bound to be a new flood of regulations by then, Mr Hutchings retorted.