'cdf - Thvi Bedford/

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

ROAD TEST

Williams

6/71

by

TaInNil:IrnaRTE Dean sgate

12-seater psv

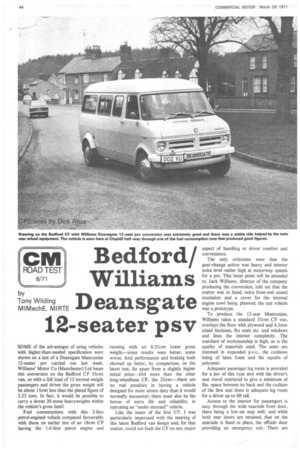

SOME of the advantages of using vehicles with higher-than-needed specification were shown on a test of a Deansgate Mancunian 12-seater psv carried out last week. Williams' Motor Co (Manchester) Ltd bases this conversion on the Bedford CF 35cwt van, so with a full load of 12 normal-weight passengers and driver the gross weight will be about 15ewt less than the plated figure of 3.23 tons. In fact, it would be possible to .carry a dozen 20-stone heavyweights within the vehicle's gross limit!

Fuel consumptions with this 2-litre petrol-engined vehicle compared favourably with those on earlier test of an 18cwt CF having the 1.6-litre petrol engine and running with an 8.25 cwt lower gross weight—some results were better, some worse. And performance and braking both showed up better, by comparison, on the latest test. So apart from a slightly higher initial price—£64 more than the other long-wheelbase CF, the 25cwt—there are no real penalties in having a vehicle designed for more severe duty than it would normally encounter; there must also be the bonus of extra life and reliability in operating an "under-stressed" vehicle.

Like the tester of the first CF, I was particularly impressed with the steering of this latest Bedford van design and, for that matter, could not fault the CF on any major aspect of handling or driver comfort and convenience.

The only criticisms were that the gear-change action was heavy and interior noise level rather high at motorway speeds for a psv. This latter point will be attended to. Jack Williams, director of the company producing the conversion, told me that the matter was in hand, extra front-end sound insulation and a cover for the internal engine cowl being planned; the test vehicle was a prototype.

To produce the 12-seat Mancunian, Williams takes a standard 35cwt CF van, overlays the floor with plywood and 4.5mm inlaid linoleum, fits seats etc. and windows and lines the interior completely. The standard of workmanship is high, as is the quality of materials used. The seats are trimmed in expanded p.v.c., the cushions being of latex foam and the squabs of polyester.

Adequate passenger leg room is provided for a psv of this type and with the driver's seat travel restricted to give a minimum of 8in. space between its back and the cushion of the first seat there is adequate leg room for a driver up to 6ft tall.

Access to the interior for passengers is easy through the wide nearside front door, there being a low-set step well; and while both rear doors are retained, that on the nearside is fixed in place, the offside door providing an emergency exit. There are three large windows on each side of the vehicle, the centre ones having half-width sliding portions; air-extractor louvres are fitted above the rear door. A KL 5Kw saloon heater supplements the normal equipment of the CF and this is located under the rearmost double seat on the offide. Interior lighting is by two transistorized fluorescent units fitted in the roof, and a CTC fire extinguisher and first aid kit are provided; a 31b BCF controllable-discharge extinguisher can be supplied at extra cost.

The Bedford van used by Williams for the conversion is perfectly standard with 120.5 cu in (2-litre) petrol engine giving 72.4 bhp net at 5400 rpm and four-speed synchromesh gearbox. The vehicle tested had the lower, 5.22 to 1, rear axle which should be quite adequate for all requirements, combining good gradientclimbing ability with a maximum speed in excess of 80 mph; the alternative (4.45 to 1) axle would be slightly worse on hills but would provide the ratio for a 95 mph maximum speed!

Before starting actual testing the Mancunian was driven on the motorway and on a narrow, twisting country road to reach the area where performance figures were to be obtained. This gave an early opportunity to assess the qualities of the model's steering, handling and suspension characteristics. All were first class. On M1 the CF could be driven at the maximum permitted 70 mph with only the minimum of attention paid to steering. It followed the chosen line without the slightest tendency to wander and there was no sign of proneness to over-correction.

On the winding country road, irregularities in the surface did not affect the steering, which was very light, and there were no oversteer or imdersteer tendencies. The suspension gave a very smooth ride for driver and passengers—there was no bouncing—and the brake and clutch pedals were light to operate.

All controls were found to be well placed, visibility was good and the area covered by the wipers satisfactory. The vehicle had the small round exterior mirrors which are now replaced on production with larger rectangular types. The small mirrors gave an inadequate rear view, whereas the current fitting will be quite satisfactory.

Fuel consumption was first assessed. The series of seven runs was made on the usual six-mile out-and-return journey on A6 between a point north of Barton in the Clay and Clophill, Beds. The fully laden figures obtained on these tests ranging from 23.5 mpg when non-stop at 40 mph to 14 mpg when stopping four times in each mile suggest that an operator will get reasonably low fuel bills with this vehicle.

Considering the figures for the part-laden and unladen runs I would estimate that on normal types of work between 22 and 24 mpg should be obtainable. The high-speed fuel consumption check was made on the 15.8-mile section of M1 from the junction of the motorway spur with A6 and down to the A4147 turn-off and back. The 15.8 mpg obtained here shows that the CF 35cwt is rather more thirsty when driven hard and fast and if such running plays a part in vehicle's operation there will be a lower overall figure than I have suggested.

Brake tests were carried out just off A6. As would be expected from a vehicle subjected to maximum-pressure braking at a considerably lower weight than the designed figure, all wheels locked on every stop. The actual figures obtained were nevertheless very good-and better than those obtained on the 18cwt CF. Because of the locking, the front of the vehicle veered towards the nearside edge of the road, but even from 30 mph the movement was never excessive. The handbrake stopped the vehicle quickly too-with both wheels locked-and 42 per cent was recorded on the Tapley meter as against 37 per cent with the 18ewt.

Acceleration tests were carried out on the same stretch of road and the test vehicle produced times normally achieved on much

lighter vehicles. On the direct-drive tests 10 mph was rather low for top gear to be engaged but initial roughness in the transmission disappeared at about 13 mph and from then on there was a smooth, steady acceleration the whole way.

The high level of performance illustrated on the acceleration tests was confirmed in maximum-power hill climbing at Bison Hill, nr Dunstable. Controllability also showed up well here when the bend 200yd from the start was reached at 33 mph. There was relatively little roll as the vehicle was driven through the turn in a completely stable manner. And the climbing time of lmin 51.2sec is comparable with that normally obtained with light vans.

Although the lowest gear needed on the climb was second, a restart on the 1 in 6.5 section was not possible in this gear even with induced clutch slip. But an easy restart was made in first and a similar result was obtained in reverse when facing down this steepest part of the slope.

During the morning brake tests there had been signs that efficiency was improving progressively. The Deansgate had only covered 1400 miles of so at the start of my tests so possibly the brake linings were not fully bedded in initially. The work they had been called upon to do during the day had clearly helped in this direction as the "fade" test down Bison showed an improvement in efficiency—to 93 per cent as compared with the peak of 86 per cent on the cold-chum tests.

The light handling characteristics, excellent steering and other factors already commented upon made the CF tested a far-from-tiring vehicle to drive. Except for the heavy gear-change, the effort was not far removed from that needed to drive a car and with the excellent driving seat provided the CF was as comfortable as most.

The price of the vehicle as tested is £1857. This is made up as follows: the conversion costs £647, the basic van price £1120, plus painting at £49, spare wheel etc. £22, under-body protection £12.50 and certificate of fitness £6.50.