Battleship did: Destroyer Performance

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

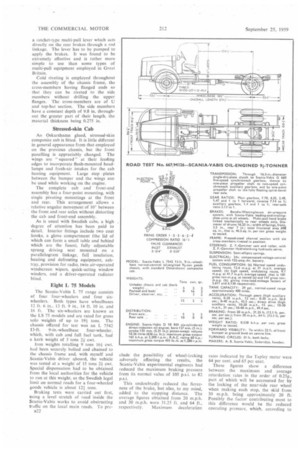

Latest Scania-Vabis Heavy-duty Fourwheeler, Has 165 b.h.p. Oil Engine, Giving High Performance and Commendable Fuel Economy By John F. Moon, A.M.I.R.T.E. APOLICY of steady design progress led to the announcement, last year, of the Scania-Vabis L75 maximum-capacity four-wheeled goods chassis to succeed the L 71 model introduced some four years earlier. The latest type offers better all-round performance than its predecessor, even with some 2 tons greater gross weight than the L 71 tested five years ago (The Commercial Motor, November 19, 1954).

Perhaps the most marked difference between the current chassis and the model it replaces is the new power unit, which, although only slightly larger, offers greatly improved power characteristics. Other less-obvious changes include a new chassis frame with heavier side members, a new rear axle and the discontinuance of a transmission hand brake.

Fuel economy is viewed with almost as much importance in Sweden as it is in Great Britain and in this respect the L 75 should prove a popular choice, as the new engine offers greater economy in terms of payload tonm.p.g. than did the D 642 150 b.h.p. unit formerly manufactured by ScaniaVabis.

A fuel-consumption test made over a difficult, undulating route at an average speed of 31 m.p.h. resulted in a consumption rate of 12.6 m.p.g., which is only 0.8 m.p.g. heavier than was obtained in 1954 with an L71 under similar conditions, but with 2 tons less load.

Despite the additional weight being carried, overall liveliness has suffered surprisingly little, the acceleration up to 30 m.p.h. from a standstill. being only 1.1 sec. slower than was obtained in 1954. Indeed, it is only in respect of braking performance that the higher gross weight seemed to have a detrimental effect, the average stopping distance recorded from 30 m.p.h. being some 11 ft. greater. General handling has been improved, although even on the old vehicle it reached a high standard, and this is particularly so with regard to the suspension.

The power unit is the Scania-Vabis D 10 ROI 10.26-litre six-cyfindered direct-injection unit, the gross output of which is 165 b.h.p. at the governed speed of 2,200 r.p.m. It is basically

similar to the engine of the CF 75 bus (The Commercial Motor, August 28). Its output is 15 b.h.p. greater than that of the 9.35-litre unit which it supersedes, whilst the torque rating of 455

lb.-ft. is 35 lb.-ft. higher. Although the new and old engines are similar in basic conception, the new unit has nothing in common with its predecessor, the bore being slightly greater and the stroke less.

An important new feature concerns the lubrication system, which, as described in the road-test report of the CF 75, incorporates a cyclonic by-pass section which feeds dirty oil into a er centrifugal filter. A further le change is that, whereas the r unit had three two-bore cylinder , the latest engine has two bore heads. Wet centrifugally :ylinder liners are retained and. fore, the light-alloy pistons have dal combustion cavities in them. a valve stems are chromium1, with Stellited heads. The crankthe journals of which are finished Ind polishing, carries a fluid-type tion damper at its forward end. a fuel-injection equipment is by

and twin paper-element fuel are mounted in front of the forcylinder head for easy access. simple oil-bath air cleaner is ted directly on the inlet-manifold ri housing.

exhaust brake (not fitted to the e tested) can be linked mechanico a control lever on the steering in, movement of the lever cutting e fuel supply also. The linkage Tconnected with the clutch pedal, it if the pedal is depressed with Khaust brake applied, the brake is automatically opened and the a does not stall. A live-speed synchromesh gearbox is unit-mounted with the engine, and the case incorporates a pocket in the left side in which any metallic, particles in the oil are trapped on a. magnetic plug. An auxiliary gearbox is available and was fitted to the test vehicle. This has ratios of 1.4 and 1 to 1 and has synchromesh engagement.

The normal rear axle is a spiral-bevel unit of robust proportions, which is fitted with an air-operated differential lock as standard. Ratios of 5.71 or 5.13 to I are offered. When this axle is specified the manufacturers' gross weight limit is 15 tons. For dumper and other heavy-duty applications a double-reduction axle is recommended. This has spiral-bevel primary gearing and helical-spur secondary gears, the overall reduction being 5.91 to I. This axle also has a differential lock as standard equipment, engagement being by means of compressed air, with spring-pressure disengagement.

Conventional semi-elliptic springs are used at both axles, the rear springs being the same length as thOse of the L 71 series. The front springs are longer-53 in. compared with 44+ in.—giving better riding and steering characteristics. Another suspension improvement concerns the use of threaded spring bolts. These increase the lubricated area, and act as seals to retain lubricant and exclude dirt.

The foot brake system of L 75 models is identical to that employed on the L 71, consisting of Scania-Vabis cam-actuated leading-and-trailing-shoe units with Bendix-Westinghouse air pressure operation through diaphragm chambers and worm-type adjusters.

The current hand brake consists of

a ratchet-type multi-pull lever which acts directly on the rear brakes through a rod linkage. The lever has to be pumped to apply the brakes. It was found to be extremely effective and is rather more simple to use than some types of multi-pull equipment employed in Great Britain.

Cold riveting is employed throughout The assembly of the chassis frame, the cross-members having flanged ends so that they can be riveted to the side members without drilling the upper flanges. The cross-members are of U and top-hat section. The side members have a constant depth of 9.8 in. throughout the greater part of their length, the material thickness being 0.275 in.

Stressed-skin Cab

An Oskarshamn glued, stressed-skin composite cab is fitted. It is little different in general appearance from that employed on the previous chassis, but the front panelling is appreciably changed. The wings are " squared" at their leading edges to incorporate flush-mounted headlamps and fresh-air intakes for the cab heating equipment. Large step plates between the bumper and the wings can be used while working on the engine.

The complete cab and front-end assembly has a four-point mounting, with single pivoting mountings at the front and rear. This arrangement allows a relative angular movement of 10° between the front and rear axles without distorting the cab and front-end assembly.

As is usual with Swedish cabs, a high degree of attention has been paid to detail. Interior fittings include two coat hooks, a glove compartment (the lid of which can form a small table and behind which are the fuses), fully adjustable sprung driving seat mounted on a parallelogram linkage, full insulation, heating and defrosting equipment, ashtray, provision for radio, twin air-operated windscreen wipers, quick-acting window winders, and a driver-operated radiator blind.

Eight L 75 Models The Scania-Vabis L 75 range consists of four four-wheelers and four sixwheelers, Both types have wheelbases 12 ft. 6 in., 13 ft. 9 in., 14 ft. 10 in. and 16 ft. The six-wheelers are known as the LS 75 models and are rated for gross solo weights of up to 191 tons. The chassis offered for test was an L 7542 13-ft. 9-in.-wheelbase four-wheeler. which, with cab and full fuel tank, had a kerb weight of 5 tons 24 cwt.

Iron weights totalling 9 tons 161 cwt. had been securely bolted and chained to the chassis frame and, with myself and Scania-Vabis driver aboard, the vehicle was tested at a weight of 15 tons 21 cwt. Special dispensation had to be obtained from the local authorities for the vehicle to run at this weight, as the Swedish legal limit on normal roads for a four-wheeled goods vehicle is about 121 tons.

Braking tests were carried out first, using a level stretch of road inside the Scania-Vabis works to avoid obstructing traffic on the local main roads. To pre 1522

elude the possibility of wheel-locking adversely affecting the results, the Scania-Vabis experimental engineers had reduced the maximum braking pressure from its normal value of 105 p.s.i. to 82 p.s.i.

This undoubtedly reduced the fierceness of the brake, but also, to my mind, added to the stopping distance. The average figures obtained from 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. were 31.25 ft. and 64 ft., respectively. Maximum deceleration

rates indicated by the Tapley meter were 64 per cent. and 65 per cent.

These figures show a difference between the maximum and average retardation rates in the order of 0.25g., part of which will be accounted for by the locking of the near-side rear wheel when making each stop, the skid from 30 m.p.h. being approximately 20 ft. Possibly the factor contributing most to this difference would be the reduced operating pressure, which, according to )scillograph traces made during these accounted for 0.35 sec. between application of the brake pedal and neneement of braking.

30 m.p.h. this would be equivalent distance of about 15 ft. If this 15 ft. I have been eliminated, the average maximum figures would have been St identical.

might be expected in view of the le output, particularly good accelerafigures were achieved and for this the auxiliary gearbox was left in its ratio. When making the runs een a standstill and 40 m.p.h., id, third. fourth and top gears were oyed and little time was lost when ng changes, as the synchromesh ianism, although almost proof ist clashing the gears, does not .eably slow up the ging action.

hen making the direct. tests between 10 m.p.h. 40 m.p.h. the vehicle d away reasonably combly float an indicated .ph. in this ratio, the trace of roughness rring between 12 m.p.h. 5 m.p.h. This indicates rkable engine flexibility emphasizes the excellent ;peed torque output of tew engine.

vo sets of fuel-con>tion figures were taken, ; a narrow undulating :h of road between rtalje and Rosenhill, the d triplotalling 16.6 miles. The first vas made without exceeding 34 m.p.h., g conditions comparable to those in t Britain. This produced a consumprate of 12.6 m.p.g. at 31 m.p.h. ige speed.

the second run a maximum speed D m.p.h. was maintained wherever itions would allow, with an average of 41.7 m.p.h.. but the consumprate did not drop as severely as d-9.7 m.p.g.

Remarkable Results

th these results gave excellent timemileage factors of 5,611 and 6,130 ctively. These figures are appiey higher than are normally returned amparable British heavy-duty fourled chassis of this type under similar itions. It would be safe to assume had the chassis been running with iwbar trailer at. say. 24 tons gross weight at normal British speeds, a figure better than 9 m.p.g.—possibly .p.g.—would have been returned. etabacken Hill, close to the Scanias factory, was used for the hill-climb arake-fade tests. This slope is half e long and has an average gradient ,aching 1 in 9. The climb, made in nbient temperature of 53° F.. occu1 min. 42 sec., of which 32 sec. were in second gear. high auxiliary, so there were still three ratios in hand. ascent produced a coolant-temperarise of only 4° F.

check for fade resistance, the L 75 was coasted down the hill in neutral, keeping the foot brake lightly applied to restrict the maximum speed to 20 m.p.h. This test lasted 13 min. and at the bottom of the hill, full-pressure application of the brakes produced a Tapley meter reading of 35 per cent., indicating a reduction in efficiency of some 30 per cent.

This is more than I would have expected, but can partly be explained by increased wheel-locking on the somewhat loose surface of the slope. Had the road surface been strictly comparable with that on which the original brake tests were made, I am sure that a higher figure would have resulted, as there is adequate facing and drum area to combat fade problems under normal service conditions.

From Tvetabacken Hill 1 drove to Sankt Ragnhildsgatan. a hill in the centre of Sodertalje, with a maximum gradient of 1 in 5.8. On this slope the vehicle was stopped and the hand brake held it without any physical effort being necessary. Several smooth restarts were made in second gear, high auxiliary, but an attempt to get away in the next highest ratio—third-low -resulted in excessive clutch slip and negligible forward motion.

I in 2f Surmountable

At this gross weight, with a 5.13 to 1 axle (the highest ratio available) a gradient of at least 1 in 21 should be manageable. using the lowest ratio in both gearboxes. The option of an even higher axle ratio might be advisable for those operators who would not be likely to haul a trailer in hilly country.

The use of a higher ratio would, additionally, give even better fuel economy and a higher maximum speed. that of the test vehicle being in the region of 55 m.p.h. Alternatively, the gearing of the vehicle as tested would enable a start to be made on a 1 in 4 gradient when running at a gross train weight of about 27 tons—a typical figure for Swedish conditions.

The vehicle was particularly easy and comfortable to drive and. although the ride did tend to become a little harsh over had road surfaces at times, it left little to be desired on the normal highway. The driving position is good. as is usual with Scania-Vabis designs, the large steering wheel being nicely raked to give a sports car-like driving position without appreciably reducing forward visibility.

Steering was generally satisfactory. there being no suspicion of " shake" on any surface, partly because the provision of disc-type dampers on the king-pins reduces any tendency for shimmy to occur. The Z.F. hydraulic servo was of great assistance in view of the front-axle loading of more than 5 tons and for the most part it worked smoothly, although at times I did notice a slight lag before it took effect, particularly at low speeds.

Because of all the cab insulation and the forward position of the engine, little engine noise penetrated the cab, and no transmission noise was observed at any ti fle.

The gearbox gives a good change despite the long lever travel. Although the use of the auxiliary box proved unnecessary during the course of normal testing, I was able, because of its synchromesh action, to make easy changes between the high and low ratios while on the move.

The rather long bonnet did not materially affect forward vision, although it increased the blind spot immediately ahead of the front bumper on the ground. The length of the bonnet. however, carries with it the usual advantages of a normal-control design in respect of engine accessibility.

Good Accessibility There was no time to conduct maintenance tests, but visual inspection of the power unit showed that none of its accessories should be difficult to t.each.

The L 75 is an excellent example of the best of Swedish engineering. It offers good fuel economy, the ability to maintain fast long-distance schedules, nearideal driving conditions and a high standard of workmanship. This is particularly so with regard to the engine, which, because of its highly effective lubricating-oil filtration system. should have an even longer life than its predecessor. The earlier engine. I might add, regularly returns mileages of well over 250,000 between maintenance periods. Although not cheap, the chassis will undoubtedly find favour with discerning operators.

Another important aspect with regard to this vehicle is the highly efficient world-wide Scania-Vabis service organization. The service department at Sodertalje is frequently able to airfreight service parts to an operator in another part of the world so that he receives them within 24 hours.

The efficiency of the service department is helped by the relatively small number of different types of goods chassis produced.