Claiming for Loss of Earnings

Page 54

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IHAVE had some correspondence recently about insurance claims for loss of earnings, and they culminated in a visit of an accountant who wanted some advice on the same subject. He showed himself to be so lacking in understanding of the problem that it seemed to me that a further reference to the subject in these articles was due.

Loss of earnings is the claim which an operator makes when, as the result of an accident, his vehicle has been out of commission for a period and he claims, through his insurance company, not only for the expense of repairing the vehicle, but for consequential loss because he has lost the use of the vehicle for a period. The subject is often misunderstood because instead of referring to it as loss of earnings it is described as loss of profits. That is a serious mistake, for a claim for loss of earnings can be, and usually is, much greater than a claim for loss of profits only, would be.

The best way to deal with the matter is to set it down as a formula and to explain it. The claim should be for the probable total earnings of the vehicle during the period, less savings accrning to the operator because the vehicle is not in service and therefore not consuming fuel, oil and tyres, nor costing anything for maintenance or for depreciation as calculated on a mileage basis.

The items to be considered are: (1) total anticipated earnings for the period; (2) establishment costs for that period; (3) standing charges exclusive of wages; (4) wages: (5) running costs. It should be realized that all the expenditure covered by items (2) and (3) still continue to be incurred and should be included in the claim,

Standing Off Driver As regards (4), wages, whether that should be included depends upon whether the driver of the vehicle can be otherwise employed so that his wage is not a loss to the operator, or whether he must be paid a wage while stood off. All the expenditure for (5), running costs, is presumed to be saved so that the operator cannot claim for that. The claim therefore comprises the total probable earnings for the period less running costs and possibly wages.

Take the case of an 8-ton vehicle covering approximately 400 miles a week and earning £35 gross. It is out of work for five weeks so that the operator loses a total revenue of £175. The running costs comprising expenditure of fuel, lubricants, tyres, maintenance (c) and probably the proportion of depreciation can he shown to amount to 7.3d. per mile. That is equivalent to £12 3s. per week, which the operator saves because the vehicle is not on tble road. The total saving for five weeks is £60 16s. 8d., an on that basis the claim should be £114 3s. 4d.

That would be a fair claim if the circumstances were such that the driver could not he otherwise employed, but had to be paid his wage. If, however, he can be put on to another vehicle or given employment of some sort, it is not fair to debit the amount of his wage against the claim. Taking his wage as £6 per week, that is a further £30 to be

A36 deducted from the £114 3s. 4d., leaving £84 3s. 4d. as the claim.

To show the sort of misunderstanding that arises, I should explain that this accountant who called upon me was arranging to deduct the establishment costs and I had difficulty in persuading him that that was an error. I pointed out to him that the establishment costs could not he avoided just because one vehicle of a fleet was off the road, nor could they be in any way diminished. All the various items, management, clerical wages, office rent and rates, telephones, would still be running on. There would only be a proportion of the total of establishment costs involved, because there would be other vehicles of the fleet still running. Nevertheless, that proportion normally debited against the damaged vehicle should be covered in the claim. Similarly, the standing charges, licence, insurance, garage rent and interest of capital outlay all continue to be paid.

Seeing the Light To illArate what might apply in his own case, I asked him to assume that there had been a fire at his office which made it impracticable for him to continue to work in the normal way. I said: "You would still have to pay your clerks, your office boy, your rent and so on, and you would want the insurance company to reimburse you on those accounts." That, I think, made him see the light, for he eventually came round to my way of thinking.

Now to change the subject. I have been accused of encouraging rate-cutting, which is surprising after all these years. My critic bases his accusation on the article which appeared in last week's issue wherein I assumed an average speed of 30 mph. for vehicles engaged in the haulage of stone blocks. I calculated my rates on that basis and he points out that in so doing I am penalizing the haulier who adheres strictly to the legal speed limit and can certainly not average 30 m.p.h. Still worse, he pointed out, is the case of the 8-tonner which must of necessity be a 20-m.p.h. vehicle.

He offers the further criticism that in the calculation of speeds I gave 6 m.p.h., 15 m.p.h. and 20 m.p.h.. for the first three 4-miles of the journey, but made no similar provision for the slackening of speed in the last 15 miles, As a matter of fact, I touched upon this matter of exceeding the speed limit in the article and admitted my fault but pointed out that I was dealing with things as they are and not as they should be. However, it seems only fair that I should answer the criticism in some way, and I propose to do so by getting out a fresh set of figures based on the assumption that the driver of the vehicle works to rule in this matter of speed.

I should begin by saying that although I apparently made provision for lower speeds for 11 miles of the journey, I really meant that to be interpreted as t-mile at each end. I gave it as 15 miles in order to simplify the calculations. I make that more clear in this present exposition, with a couple of diagrams.

In Fig. 1, I show the distances and speeds as they would

apply in the case of a 30-m.p.h. vehicle, which I have assumed to average 25 m.p.h, during the major part of the journey. Reference to the diagram will show that for he first quarter of an hour I assume an average speed of 6 m.p.h. so that a quarter of a mile takes 21 mins, During the next quarter of a mile, the average speed is assumed to be 12 m.p.h., taking 1,1 mins., and for the third quarter of a mile, 18 m.p.h., or the time of approximately I min. At ihe other end of the journey the last 1-mile ,s given the same times, but, of course, in reverse.

This shows how absurd the whole business of calculating speeds can be. The majority of drivers of vehicles engaged on this class of work, so soon as the vehicle is loaded starts off with foot hard down on the accelerator pedal, changing up to top gear as quickly as possible. If there be no patrol cars about, the foot is kept down hard on the accelerator irrespective of the speed limit until the end of the journey is in sight, which is certainly not anything like 1-mile away. The brake is then applied hard. Theoretically, however, the diagram indicates what may happen in the case of the driver who does not follow the principle of "driving on his brakes," but treats his vehicle properly and never exceeds the legal limit.

The next thing to do is to transfer these speeds and times into totals for the journeys and calculate a new set of rates on that basis. In the case of the 6-tonner, it will be recalled that the figures for time and mileage were 8s. per hour plus 10d. per mile It was also agreed that terminal delays would account for 21 hrs. I am dealing with a preliminary lead of 5 miles increasing by 5-mile steps to a maximum of 50 miles. The first thing to do is to deal with the initial 5-mile lead. For the first 1-mile I have 21 mins. plus II mins. plus 1-min., which is 4{f mins. and for the last 1-mile a similar time, so the total for 11 miles of the journey is 9? mins.

The remaining 31 miles are run at an average speed of 25 m.p.h., which is equivalent to 2.4 mins. per mile. The Lime needed to travel 31 miles is therefore 8.4 mins., and the total for 5 miles is 8.4 mins. plus 9f mins., which is, as near as matters, 172 mins. The time for the total journey, out and home, is, therefore, 351 mins. and the total time for the journey, including 21-hr. terminals, is 2 hrs. 501 mins.

I have taken that as 2 hrs. 50 mins., which at 8s. per hour amounts to El 2s. 8d. To that I add for 10 miles at 10d. per mile, 8s. 44„ and I get El lls. For that sum, 6 tons of stone block have been carried, so that the rate per ton should be 5s. 21c1., as compared with 5s. Id., which was the rate I gave last week.

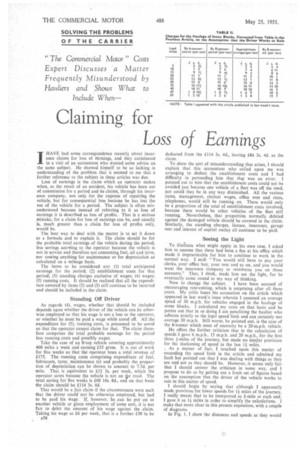

Each additional 5-mile lead involves 10 times 2.4 mins.. for during the additional mileage the vehicle is assumed to be travelling at an average speed of 25 m.p.h. At Ss. per hour, 24 mins. costs 3s. 21d. Add 8s. 4d. for the mileage charge for the 10 miles, and I get its. 61d., which is equivalent to is. 111d, per ton as' compared with ls.-10d. in the previous article. What this means for each zone is set out in the second column of Table II.

The 8-tonner, being a 20-m.p.h. vehicle, requires a different diagram and schedule for the speeds and times. The diagram I have set out in Fig. 2 and it is comparable with that in Fig. 1. I need not enlarge upon the figures, taking it for granted that the reader will understand them from what has already been stated about the Fig; I. He will appreciate that times and speeds for the three initial and three final f-mile stretches will be longer and slower in this case because we have only to reach the 20-m.p.h. maximum instead of 30 m.p.h. It can be seen from the diagram that •5 mins. are required for the initial and final 1-mile. The intervening stretch of road is covered at an average speed of 18 m.p.h., which is 31 mins. per mile.

The travelling time is therefore 5 mins. plus the time needed for 31 miles at 31 mins. per mile, which is 111 miles approximately. The total time fot the two-way journey is thus 43 mins.

For each time charge we have, therefore, the terminals of 3 hrs., plus 43 mins., say 31 hrs., and at 9s. 6d. per hour that is £1 15s. The mileage rate is Is, per mile and the rate to charge for 10 miles is 10s. The total is 45s., and at tons per load that is 5s. 71d. per ton, compared with 5s. 4d. when the legal speed limit is exceeded.

For the next 5 miles the total time would be 10 times 31 mins., which is 331 mins, and will be charged at the rate of 9s. 6d., per hour, 5s. Id. Adding 10s. for the mileage charge, the total is 15s. Id., so that Is. 101d, per ton must be added to the rate for each additional 5-mile lead.

These figures are set out in Table II, which is comparable with Table I in the previous article. As might be expected. the new figures arc less favourable to the 8-tonner than the old ones for the reason that the 8-tonner is compelled to travel at the slower speed, I have worked out the figures for the oil-engined 8-tonner on a similar basis and set out the figures for the charges for that in the final column of Table IL The extra expense of travelling at the legal limit of speed is 3d. more per ton for the 5-mile lead, rising to 2s. 6d. per ton for the 50-mile lead. This difference may reasonably be cited as an argument in support of the prevalent claim that the 30-m.p.h. limit should be applied to all sizes of vehicle. If this economy of anything up to 2s. 6d, per ton could be saved in one instance, it could be saved in hundreds and thousands of instances, and if that figure be multiplied by millions of tons of all kinds of materials which are moved each year. the benefit to the country's economy of amending the speed limit, as is so strongly urged, should be obvious.

I have now amended my figures according to the recommendations of my critic. It will be seen that the alleged rate-cutting does not amount to much in this particular case. In any event, no one will deny that although the figures in this article are correct on the basis of "working to rule," those in the previous article more accurately reflect the real position of affairs.-S.T.R.