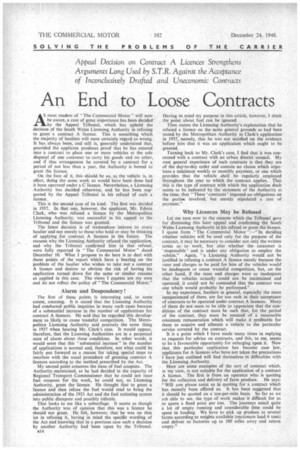

An End to Loose Contracts

Page 48

Page 51

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Appeal Decision on Contract A Licences Strengthens Arguments Long Used by S.T.R. Against the Acceptance of Inconclusively Drafted and Uneconomic Contracts Asmost readers of "The Commercial Motor" will now be aware, a case of great importance has been decided by the Appeal Tribunal, which has upheld the decision of the South Wales Licensing Authority in refusing to grant a contract A licence. This is something which the majority of hauliers will most certainly regard as wrong. it has always been, and still is, generally understood that, provided the applicant produces proof that he has entered into a contract to place one or more vehicles at the sole disposal of one customer to carry his goods and no other, and if that arrangement be covered by a contract for a period of not less than a year, the Authority is bound to

grant the licence.

On the face of it, this should be so, as the vehicle is, in effect, doing the same work as would have been done had it been operated under a C licence. Nevertheless, a Licensing Authority has decided otherwise, and he has been supported by the Appeal Tribunal in his refusal of such a licence.

This is the second case of its kind. The first was decided in 1937. In that one, however, the applicant, Mr. Edwin Clark, who was refused a licence by the Metropolitan Licensing Authority, was successful in his appeal to the Tribunal and the licence was granted.

The latest decision is of tremendous interest to every haulier and not merely to those who hold or may be thinking of applying for contract A licences in the future. The reasons why the Licensing Authority refused the application, and why the Tribunal confirmed him in that refusal, were fully reported in "The Commercial Motor" dated December 10. What I propose to do here is to deal with those points of the report which have a bearing on the problem of the haulier who wishes to take out a contract A licence and desires to obviate the risk of having his application turned down for the same or similar reasons as applied in this case. The views I express are my own and do not reflect the policy of "The Commercial Motor."

Alarm and Despondency!

The first of these points is interesting and, to some extent, amusing. It is stated that the Licensing Authority had conducted public inquiries in many such cases because of a substantial increase in the number of applications for contract A licences. He said that he regarded this development as likely to cause wasteful competition. 'The Metropolitan Licensing Authority said precisely the same thing in 1937 when hearing Mr. Clark's case. It would appear, therefore, that the Licensing Authorities are in a perpetual state of alarm about these conditions. In other words, itwould seem that this "substantial increase" in the number of applications is normal and, therefore, not what could be fairly put forward as a reason for taking special steps to interfere with the usual procedure of granting contract A licences according to the method prescribed by the Act.

My second point concerns the issue of fuel coupons. The Authority maintained, as he had decided in the capacity of Regional Transport Commissioner that he could not issue fuel coupons for the work, he could not, as Licensing Authority, grant the licence. He thought that to grant a licence and then refuse the fuel would tend to bring the administration of the 1933 Act and the fuel rationing system into public disrepute and possibly ridicule.

That looks to me like a subterfuge. It seems as though the Authority was of opinion that this was a licence he should not grant. He felt, however, that he was on thin ice in refusing it, having in mind the specific wording of the Act and knowing that in a previous ease such a decision by another Authority had been upset by the Tribunal. Having in mind my purpose in this article, however, I think the point about fuel can be ignored.

Then comes the Licensing Authority's explanation that he refused a licence on the same general grounds as had been stated. by the Metropolitan Authority in Clark's application in 1937, namely, that he was not satisfied on the evidence before him that it was an application which ought to be granted.

Turning back to Mr. Clark's case, I find that it was concerned with a contract with an urban district council. My own general experience of such contracts is that they are of the day-to-day order and contain no clause which stipulates a minimum weekly or monthly payment, or one which provides that the vehicle shall be regularly employed throughout the year to which the contract applies. That • this is the type of contract with which the application dealt seems to be indicated by the statement of the Authority at the time; that "These contracts' imposed no obligations on the parties involved, but merely stipulated a rate of payment."

Why Licences May be Refused Let me turn now to the reasons which the Tribunal gave for dismissing this later appeal and confirming the South Wales Licensing Authority in his refusal to grant the licence. I quote from "The Commercial Motor ":—"In deciding whether vehicles will be used only for the purpose of the contract, it may be necessary to consider not only the written terms as to work, but also whether the customer is 'responsible' and is under any obligation to employ the vehicle." Again, "a Licensing Authority would not be justified in refusing a contract A licence merely because the rates and charges to be paid for hire of the vehicles would be inadequate or cause wasteful competition, but, on the other hand, if the rates and charges were so inadequate that the vehicles actually could not be maintained and operated, it could not be contended that the contract was one which would probably be performed." In my experience, hauliers in general, especially' the more inexperienced of them, are far too rash in their acceptance of contracts to be operated under contract A licences. Many of them do not seem to be able to appreciate that the conditions of the contract must he such that, for the period of the contract, they must be ensured of a reasonable minimum remuneration which will make it profitable for them to acquire and allocate a vehicle to the particular service covered by the contract.

It is a point which I have made many times in replying to requests for advice on contracts, and this, to me, seems to be a favourable opportunity for enlarging upon it. Now that this particular application has become case law, applicants for A licences who have not taken the precautions I have just outlined will find themselves in difficulties with the Licensing Authority.

Here are some examples of the sort of contract which, in my view, is not suitable for the application of a contract A licence. The first is from an operator who is quoting for the collection and delivery of farm produce. He says: Will you please assist us in quoting for a contract which has recently been offered us. It has been suggested that it should be quoted on a ton-per-mile basis. So far as we are able to see, the type of work makes it difficult for us to quote a fixed price per ton. The journeys entail quite a lot of empty running and considerable time could be spent in loading. We have to pick up produce at several farms according to weights available (maximum load 6 tons) and deliver to factories up to 100 miles away and return empty."

Here is an operator who is being asked to quote on a ton-per-mile basis for work executed under a contract A licence and he is offered no sort of guarantee as to the volume of work available. I should imagine this would he a particularly dangerous contract to enter into, because it deals with farm produce. From an examination of the type of produce which this operator is to carry, it seems to me that there would be regular work for the vehicle for only some three or four months in the year. For the rest of the time his vehicle would be idle and he would be getting no payment, as there is no suggestion of a guaranteed minimum mileage or ton-mileage.

In another case, the operator was invited to put in a tender for a vehicle to be contracted for over a period of 12 months, and he was asked to quote on a tonnage basis for distances up to 10 miles, from 10 to 20 miles, from 20 to 30 miles, and so on. He was requested to quote for full loads and any extra charge for split deliveries. Here, again, there is no guarantee of work throughout the year. It is quite likely that for a large proportion of the year the operator would be without work for the vehicle and would have to stand a loss.

In both those cases I pointed out to my correspondents that these were not contracts to which a *contract A licence vehicle could suitably be applied. In both cases I indicated the conditions for which they should ask. In my opinion, municipal, highway authority and county council contracts are not suitable subjects for contract A licences. A typical paragraph from all such agreements is this: " No payment will be made for men or vehicles standing idle by reason of quarry plant break-down, nondelivery by railway or dock company, strikes, inclement weather, or any other cause whatever.", As a point of fact it is not common for operators to try to obtain contract A licences for this class of work. If they have had experience they will be aware that it is unlikely that work will be found for their vehicles throughout the year. If. therefore, they take out contract A licences and are honest in their attitude towards those licences—that is, if they steadfastly refrain from using those vehicles concerned for any work outside' the contract— they must know it is extremely likely that the number of idle days or weeks in the year will entirely offset any profit which they would otherwise make from the contract itself. This criticism applies particularly to municipal and county council contracts, because the payments usually show only a small margin of profit.

I can well appreciate the reason for the Metropolitan Licensing Authority's refusing the contract A licence of Mr. Clark in 1937. I should have done the same myself.

Here (is another extract from a form of contract for an A licence into which a correspondent of mini was proposing to enter. It reads: "The merchants shall pay the contractor at the rate of 14s. per load of 3 tons." That was the only reference to payment. There was no guarantee of any minimum fee or of any maximum tonnage. In an appropriate form of agreement for a contract A licence the following paragraph invariably appears: "The hirer shall

pay the contractor a minimum sum of £ , for a minimum mileage of miles per week of 44 hours per week.

Any excess mileage to be charged at the rate of per mile."

An operator entering into an agreement containing a clause such as that, and having also the good sense to see that the minimum amount which he is to receive per week for a given maximum mileage is sufficient to cover his costs, provide for contingencies, and pay him a profit, need have nothing to fear either in the execution of the work, or, to my mind, in the way of a potential refusal of a licence from the Licensing Authority. That clause, as I see it, is an essential safeguard for all parties concerned.

To turn again to the more general aspects of the matter, I feel sure that this decision of the Tribunal will be welcomed by the majority of bona tide hauliers. As is well known, there has been for a long time the feeling among genuine operators that contract A licences have been abused. Operators have obtained them by the simple means of producing a signed contract for a period of years with a customer. Having obtained the licence they have within a short time been using the vehicle generally for hire or reward.

A point made by the Licensing Authority and the Tribunal is that a good deal of this kind of thing has'been brought about by the fact that the contracts themselves were unsatisfactory. They were unsatisfactory for precisely the reasons I have quoted; that they were not so drawn up as to ensure to the operator an adequate revenue throughout the whole of the year. The operator, quickly finding that under the terms of the contract he was paid only for what he did. and that the work offered was inadequate to enable him to meet his expenses, has been forced to look elsewhere for work, thus breaking the law and competing with his

fellow hauliers who were legitimately engaged in that class of work.

There is, I feel, a sinister significance in the statement by counsel representing the Road Transport Executive that the B.T.C. wished to assume with confidence, after "the appointed day " when contract A licensees applied for permits to carry beyond 25 miles, that a licence had been granted to meet only the legitimate needs of industry. There will be many operators not due to be acquired under the Transport Act who will, as soon as the need arises, apply for permits to travel beyond the 25-mile radius. Not all of them will be lucky, if that be the right word to use. If those amongst them who are operating under contract A licences wish to continue to operate under those licences and run beyond the statutory limit of 25 miles radius, it will be just as well to see that the vehicles they are operating under contract A licences can be justified if that operation is tested in accordance with the principles just laid down.

These principles, in plain terms, are that the contract must be such that the rates which the operator receives can be shown to be economic, providing for all essential operating and administrative expenses plus a profit throughout the whole term of the contract.

Now as to a point which is not perhaps relative to this particular problem, but which indicates a possible way out for the genuine operator who wishes to enter into a bona fide contract with an ancillary user, arrangements can often be made to register the vehicles in the name of the trader and operate them under C licences. The user will thus become responsible for the licensing and insurance and for the employment of the drivers, but all other expenditure can be borne by the haulage contractor undertaking the contract. Under those conditions the question of applying for a contract A licence does not arise. S.T R.