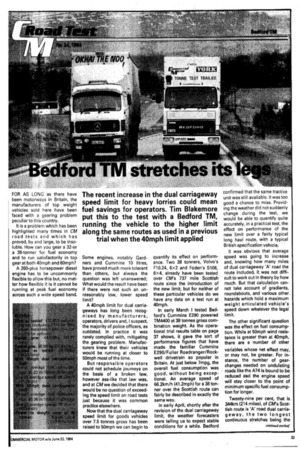

The recent increase in the dual carriageway speed limit for

Page 18

Page 19

Page 22

Page 25

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

heavy lorries could mean fuel savings for operators. Tim Blakemore put this to the test with a Bedford TM, running the vehicle to the higher limit along the same routes as used in a previous trial when the 40mph limit applied

FOR AS LONG as there have been motorways in Britain, the manufacturers of top weight vehicles sold here have been faced with a gearing problem peculiar to this country.

It is a problem which has been highlighted many times in CM road tests and which has proved, by and large, to be insoluble. How can you gear a 32-or a 38-tonner for fuel economy and to run satisfactorily in top gear at both 40mph and 60mph?

A 200-plus horsepower diesel engine has to be uncommonly flexible to allow this but, no matter how flexible it is it cannot be running at peak fuel economy across such a wide speed band. Some engines, notably Gardners and Cummins 10 litres, have proved much more tolerant than others, but always the question was left unanswered; What would the result have been if there were not such an unreasonably low, lower speed limit?

A 40mph limit for dual carriageways has long been recognised by manufacturers, operators, drivers and, I suspect, the majority of police officers, as outdated. In practice it was rarely complied with, mitigating the gearing problem. Manufacturers knew that their vehicles• would be running at closer to 50mph most of the time.

But responsible operators could not schedule journeys on the basis of a broken law, however ass-like that law was, and at CM we decided that there would be no question of exceeding the speed limit on road tests just because it was common practice elsewhere.

Now that the dual carriageway speed limit for goods vehicles over 7.5 tonnes gross has been raised to 50mph we can begin to

quantify its effect on performance. Two 38 tonners, Volvo's F10.24, 6x2 and Foden's S106, 6x4, already have been tested over CM's 737 mile Scottish route since the introduction of the new limit, but for neither of these particular vehicles do we have any data on a test run at 40mph.

In early March I tested Bedford's Cummins E290 powered TM4400 at 38 tonnes gross combination weight. As the operational trial results table on page 37 shows, it gave the sort of performance figures that have made the familiar Cummins E290/Fuller Roadranger/Rockwell drivetrain so popular in Britain. At just below 7mpg, the overall fuel consumption was good, without being exceptional. An average speed of 66.2km/h (41.2mph) for a 38 tonner over the Scottish route can fairly be described in exactly the same way.

In early April, shortly after the revision of the dual carriageway limit, the weather forecasters were telling us to expect stable conditions for a while. Bedford confirmed that the same tractive unit was still available. It was too good a chance to miss. Providing the weather did not suddenly change during the test, we would be able to quantify quite accurately, in a practical test, the effect on performance of the new limit over a fairly typical long haul route, with a typical British specification vehicle.

It was obvious that average speed was going to increase and, knowing how many miles of dual carriageway 'A' road the route included, it was not difficult to work out in theory by how much. But that calculation cannot take account of gradients, roundabouts, and various other. hazards which hold a maximum weight articulated vehicle's speed down whatever the legal limit.

The other significant question was the effect on fuel consumption. While at 50mph wind resis tance is greater' than at 40mph, there are a number of other variables whose net effect may, or may not, be greater. For instance, the number of gearchanges needed on undulating roads like the A74 is bound to be reduced aiad the engine speed will stay closer to the point of minimum specific fuel consumption for longer.

Twenty-nine per cent, that is 344km (214 miles), of CM's Scottish route is 'A' road dual carriageway, the two longest continuous stretches being the

sleeper cab and short wheelbase day cab models fitted respectively with a Detroit Diesel 6V 92 — TTA 226 hp engine and a Cummins LT 10 at 250 hp.

The 14-litre E290 is a relatively heavy engine and this is reflected in this TM's quite hefty kerb weight, with no spare wheel or carrier, of 6,681kg. As -the histogram shows, that -means the Bedford cannot quite manage the payload of a lightweight 4x2 such as the Gardnerengined 401, but nonetheless it does match up well to Volvo's lastest F10, the day-cabbed 4x2 with charge-cooled 9.6 litre TD 101F engine.

It is in the area of instant driver appeal where I suspect most drivers would say that the Bedford does not compare with the Scanias and Volvos of this world. I would be bound to agree that in the company of some of the latest cabs on offer in this competitive market sector, the TM is beginning to show its age.

That is not to say it is by any means a hardship to spend three days at the TM's controls. Interior noise levels are low (we measured a maximum of only 75dB (A) at the drivers ear at a steady 60mph) and Bedford has attended to the various rattles which used to plague the vehicle.

Towards the end of our second test period, a buzzing noise from the general area of the gearbox began to become apparent. Bedford's engineers say they traced this to nothing more serious than a loose exhaust mounting bracket.

Certainly the sleeper cab TM is roomy and the latest dark trim a lot more practical than the lightcoloured check material which came before it. However some sources of driver irritation persist. Mirrors foul up quickly at the first sign of wet roads (this TM was fitted with wheel nut embellishers on the front axle, but still the mirrors soon became dirty) and clutch pedal action is heavy. The latter spoils the otherwise impeccably crisp TM gearshift and makes town driving something of a chore.

This particular TM also suffered from a roof hatch which lifted in crosswinds — something which would not have been evident had a roofmounted air deflector been fitted, as it was before we tested it.

There is evidence that the customer could also benefit from lower cab heights. Air resistance. would be reduced — a factor which gained in• importance since the recent road speed limit increase was implemented, as the drag caused by frontal area increases with speed.

A reduction in height, then, offers the user some form of tangible return while, at the same time, lessening the aggressive visual impact of highcab vehicles.

Although trailers are often higher than the vehicles that pull them, they appear to represent less of an aggressive image to the onlooker, perhaps because they are seen as the passive component of the combination. They have no motive power of their own that might threaten the more intimate environment of the motor car.

The term 'aggressive' was deliberately used in this context. This quality appears to be an intentional element in many designs. Manufacturers want to ensure that their products are seen to 'look the part' to potential clients.

It is not size alone that suggests aggression. Other factors include the sharply-defined square-jawed lines of the cab panels.

Again, some effort has been

made to soften the aggressive image. Mercedes-Benz has softened the slab front approach of most manufacturers by introducing cabs that have slightly convex front panels. With a slightly protruding lower bumper, the apex of the curved front does not detract from the cab length available. Indeed, with the recent adjustment to overall dimensions some addition has been made in this direction.

Extending this theory, another major factor in portraying a fearsome image is the huge gaping and monstrous mouths formed by highly contrasting radiator grilles. This feature is accentuated by those manufacturers who insist on utilising a black grille.

The size of the grille used is often proportional to the strength of the image displayed, the larger and more highly contrasting it is, the more aggressive the visual image. Some manufacturers have reacted to the situation, as designers now appear to make a conscious effort to reduce the size of the grille.

The theory has been taken a long way by the Leyland Roadtrain, which at first sight appears to have dispensed with a grille altogether. By deliberately softening the cab corners with subtle radii as well, the designer has produced a friendlylooking vehicle which is less likely to strike fear in the hearts of the public.

In a less radical approach, Seddon Atkinson has disguised the grille assembly of its 301 by simply colour matching it to the surrounding panels, thus removing the visual contrast altogether. Another example is the new Scania with its colourmatched horizontal bars used to disguise the grille and effectively masking the element of contrast.

Other areas that could be greatly improved are front bumper and headlamps. Heavy bumpers make a heavy handed impression. They apper to sweep all before them, come what may. And some headlamps have all the appearance of piercing eyes. Where both are disguised successfully by blending them into the cab panelling, their aggressive posture is greatly reduced.

Returning to colour, while manufacturers have a definite responsibility for their product image, they are not alone in carrying this burden. Operators, also, have a significant role to play in retaining the benefits afforded them by the vehicle supplier.

On all too many occasions, the worthwhile efforts of the manufacturer are immediately destroyed by thoughtless design of livery. Many observed vehicles have been painted with commendable livery designs, some of which included re-colouring of the grille. With certain makes of vehicle, this has meant that the deliberately disguised grille has been given a new and unwanted prominence.

By subtly blending the cab outline into a thoughtful livery scheme, the outward appearance of the vehicle can be successfully softened. This can be carried over into the choice of paint colour. Perhaps the day may soon dawn when softer pastel shades will replace the harsh aggression suggested by vivid reds, oranges and yellows.

This area of sales psychology is well recognised and understood.

One day, the heavy goods vehicle may even become an accepted feature of Britain's roads. chin, which was bought last year and is now part of Andrew Hogg.

United Transport itself is owned by BET, one of the stock market's star performers in recent years.

The tanker division's success in the past two years was not because it avoided recession, but because it spotted the downturn in traffic early and met it head on. "Towards the end of 1979 we saw the signs of recession and we responded by stopping all new investment, except for specific contracts," said Mr Allen.

This meant cutting the investment budget from £4 million a year to virtually nil. Staffing levels were cut back across the board and the fleet reduced by 28 per cent. The year 1981 was a trough, but savings on interest costs and slimmed down operations brought record profits in 1982. Last year was even better, with trading performance particularly improved.

The tanker haulage market is still low, according to Mr Allen, and if anything is slightly in decline. Signs of an up-turn in 1983 are proving to be something of a false dawn.

Spot hire is beginning to gain ground against contract hire, because it is becoming cheaper due to overcapacity Mr Allen said, with small operators doing outward and return loads at backload rates.

United is looking for growth, by internal expansion, acquiring another haulier or taking over an own-account operation. Internal growth is the cheapest, but most difficult growth to achieve during the present recession. A company can do a lot of quoting, but getting traffic at a profitable rate is much more difficult.

Buying another haulier could be a particularly attractive proposition, although the ground rules for assessing a good acquisition have changed, according to Mr Allen. In the past, a buyer simply looked at the profits of the previous three to five years made by the company it wanted to acquire.

"These days the owner of the business is looking for at least the value of the assets, Mr Allen continued: "Acquisitions are now more difficult. A large proportion of the price is the goodwill factor — the value of the past to the on-going business."

Four years of recession have provided fertile ground for takeovers. Hauliers who have been starved of profits to plough back into the business and are having to replace expensive equipment may have difficulty raising the necessary capital. Even if they can do so, they may be unwilling to carry on the full burden of the investment risk. The main consideration for United, provided the business is sound, is whether or not it will fit in with the existing group activities. The acquisition can be either run independently or merged.

The structure and approach of United is well suited to hauliers which want to continue managing their operation, but want large-group backing. When buying companies United has in the past kept the original family management where possible, and aims to continue this policy. The subsidiaries retain their separate identity and a large degree of autonomy.

Managing directors of each of the subsidiary companies meet at least every two months to maintain contact within the group. Apart from that, each company has a two-pronged attack with the Chepstow headquarters to gain new business, depending on the nature of the opportunity.

Each subsidiary tends to be regarded as a specialist in particular traffics — Bulwark with beer, Ancliffe (BLT) with powders and ro-ro, for example — but United regards them all as gen eral tanker operators.

In looking for new work it wi not, however, draw the line a tanker work if other vehicles an needed for related work. So i uses curtain-siders as well a tankers in the Copenhagel Transport fleet to carry pack aged as well as bulk beer.

Arguably, the most like!, method of developing growt1 lies in gaining hire or rewan work from the own-account sec tor. Convincing own-accouri operators either to sell off o scrap their fleets is a slov process, but it has been given boost by the spring Budget an noun cement that tax allowance. are to be phased out.

"In the past, the availability 0