icania is growing itrong in Brazil

Page 31

Page 32

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

LLIONS of cups of coffee will be consumed during the tive season, and it is a fair assumption that many of the und beans reach this country in one form or another from ail. This largest of the Latin-American countries is regarded me massive coffee plantation; nothing could be further n the truth.

The place buzzes with in;trial activity, not the least of ich is its massive 12.5mkW iro-electric power station ich will be the world's bigtt when it opens in 1983. The lOOkm Transamazonica highy is another project which has : only brought work to thouids of people but it designed attract settlers in parts of 35i1'S unexplored territory ich accounts for two thirds of 81/2 million square kilometres n square miles).

It was five years ago when / first visited Brasil and since the transport industry has an developing fast to keep up th industrial development. radoxically, the Brasilian onomy has been slipping dly in the same period with lation running at between 25

d 35 per cent and the curicy being devalued against dollar almost every 30 days. is year alone, the pundits adict an adverse balance of yments of E1/2 billion. That akes any comparison with rope almost impossible. It .Ist make OH happy too.

Indeed one of the bright proects in financial terms on a sil's industrial front is the :ania plant at Sao Paulo. It es from strength to strength undoubtedly because of the .ong European influence.

This year Scania's 3,500 Nkforce will produce 3,900 mmercial vehicles of over 20 ns carrying capacity and 600 ises. The cv figure represents ) per cent of the heavy vehicle ipulation which is 10 per cent the total vehicle population. There are nine models in ;ania's Brasil range; the latest nich was developed in Brasil is e LK series. There are, hower, only three engines — the turally aspirated DL operating 203bhp, the BS 211 ierating at 296bhp and the 314 at 375bhp. Vehicles with these options are sold throughout Latin America and exported to Mozambique and Angola.

The Brasil plant is also developing the artic bus. Already there are three prototypes with four units in service. Another 2,000 are on order — Brasil is a bus hungry country. There are 100,000 in service. Most employees are carried to and from industrial complexes free and in buses.

Whether it is a bus or a cv chassis the content of vehicles produced at Sao Paulo is 90 per cent Brasilian; the other 10 per cent is bought in, much of it from South American manufacturers. Of the 8,900 components used only 1,000 are produced by Scania, and for this reason every single item is subjected to quality control checks.

Such a detailed procedure occupies 121/2 per cent of the staff at SSB and accounts for 10 per cent of the cost of the vehicle. They are proud of their record and their aim is -to maintain Swedish standards.

On the operating side of Brasilian transport 80 per cent travels by road, 18 per cent by rail, the remainder by air and water. And this despite heavy railway investment — it seems they can't get it right, either.

Where the Brasilians show us the way is in vehicle weights. Now operating at 40 tonnes gvw and 10 tonnes per axle they will shortly go up to 45 tonnes with a 10 per cent uplift on axle weights.

Vehicle dimensions will remain the same at 12 metres for a single axle, 161/2 metres on a double and 25 on a tri-axle trailer. Drawbar outfits are not favoured. There is a power to weights ratio of 6bhp per tonne. Heavy transport in Brasil accounts for 60,000 vehicles exceeding 30 tonnes carrying capacity; in the 20-30 tonne group there are 75,000, bet ween 10 and 20 there are 500,000 and up to 10 tonnes the figure is 100,000.

The licensing system, which is a bit slack, is about to be modified. There are only 10,000 registered hauliers in Brasil and they carry only 17 per cent of the country's goods. To be registered an operator he must have a carrying capacity of at least 70 tonnes; that can be accomplished by as few as three vehicles.

Of the remaining 83 per cent of traffic, 80 per cent is hauled by unregistered hauliers, mainly owner-drivers, and the rest goes by own-account operation.

The advantage of being registered is that fleet financing is made easy and there are tax benefits. The disadvantages are that the fleet, records and traf fics are open to official scrutiny. With typical Latin American logic we were told that it pays to _ _ be registered becauSe no one will trust their cargoes to unregistered operators. Yet they move 83 per cent of the traffic. There are 10,000 clearing houses, which do not enjoy the best reputation — shades of Hull.

Next year the law will be changed to ensure that all operators register; the Government should then know how many operators there are in this class. Estimates put the figure between 400,000 and 700,000.

There is also a plan to encourage the owner-drivers to form co-operatives on the lines of the British Association of Owner Drivers! They are also to be encouraged to engage in contract work only to ensure that they remain solvent.

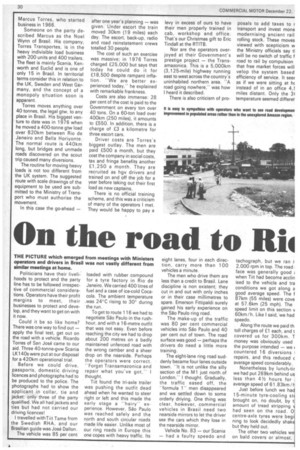

There is, however, scope for those operators who select a segment of the market either by traffics or area. Among those I met Paul Mincarance, specialist in meat haulage; halo Gallo, who is in the bulk haulage segment and still uses a Leyland Comet on c and d work; and Carlos Armouris, who is a general haulier in the north of this vast country. But the real specialist was undoubtedly Marcus Torres, who started business in 1966.

Someone on the party described Marcus as the Noel Wynn of Brasil. His company, Torres Transportes, is in the heavy indivisible load business with 200 units and 400 trailers.

The fleet is mainly Scania, Kenworth and Euclid and is one of only 15 in Brasil. In territorial

terms consider this in relation to the UK, Sweden and West Ger

many, and the concept of a monopoly situation soon is apparent.

Torres moves anything over 40 tonnes, the legal gtw, to any place in Brasil. His biggest ven ture to date was in 1976 when he moved a 400-tonne gtw load over 820km between Rio de Janeiro and Bella Horiyonte. The normal route is 440km long, but bridges and unmade roads discovered on the scout trip caused many diversions.

The routine for moving heavy loads is not too different from the UK system. The suggested route with scale drawings of the equipment to be used are sub mitted to the Ministry of Transport who must authorise the movement.

In this case the go-ahead — after one year's planning — was given. Under escort the train moved 30km (19 miles) each day. The escort, back-up, radio and road reinstatement crews totalled 30 people.

The cost of such an exercise was massive; in 1976 Torres charged £25,000 but says that today he could do it for £18,500 despite rampant infla

tion. -We are better experienced today," he explained with remarkable frankness.

Costs are also immense: 28 per cent of the cost is paid to the Government on every ton over 40 tons. On a 60-ton load over 400km (250 miles), it amounts to £550. In addition, there is a charge of £3 a kilometre for three escort cars.

Driver costs are Torres's biggest outlay. The men are paid £500 a month, but they cost the company in social costs, tax and fringe benefits another £1,250 a month. They are recruited as hgv drivers and trained on and off the job for a year before taking out their first load as new captains.

There is no official training scheme, and this was a criticism of many of the operators I met. They would be happy to pay a levy in excess of ours to have their men properly trained in cab, workshop and office. That's our Christmas gift to Eric Tindall at the RTITB.

Nor are the operators overjoyed at their Government's prestige project — the Transamazonica. This is a 5,000km (3,125-mile) highway running east to west across the country's uninhabited northern area. "A road going nowhere," was how I heard it described.

There is also criticism of pro posals to add taxes to r transport and invest mane modernising ancient rail rolling stock. These moves viewed with scepticism yv the Ministry officials say tl will be no switch of traffic f road to rail by compulsion that free market forces will velop the system based efficiency of service. It seer as if we were sitting at IN instead of in an office 4,! miles distant. Only the 31 temperature seemed differer