boxfut of noutrat

Page 20

Page 21

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

PreWorlclWar 1 engineering left the driver with problei

IF ONE compares a heavy lorry of the pre-First World War period and its modernday counterpart it could be argued that as far as the basic design concept is concerned they haven't changed very much. They are still powered by an internal combustion engine (steam devotees can turn over at this point), they still have a live rear axle, a propellor shaft, leaf springs, ladder chassis — the list goes on.

Of course, this is not being very fair as the improvements made around the same basic layout since, say, 1918 have been tremendous. But in this festive season when breakdowns do not exist, when 24hour VOR systems have improved to three days, when Alan Law sends a Christmas card to Lucas Kienzle, let us look at some of the design features of the commercial vehicle of over 60 years ago.

Most of them were petrol powered and with an in-line four configuration. Petrol engines, of course, imply electrical ignition systems, and as these have still not been perfected today it is perhaps unrealistic to expect 100 per cent reliability in 1918.

Until the advent of the high-tension magnetos, elec trical troubles probably accounted for a good half of the roadside breakdowns in those days — as well as a rapid increase in the amount of roadside profanity I shouldn't wonder.

But as I said it's the festive season so I'll draw a veil over this. Apart from that the delicate souls who carry the titles fleet engineer, service engineer et al probably wouldn't know half the words anyway. Before the magneto, the fragile accumulator often failed in its task of providing its vital spark, and this, in conjunction with the somewhat basic carburettors in use then, was enough to drive any fleet engineer hairless. The early carburettor was very much a suck-it-and-see component consisting of a float chamber, jet, choke and throttle which in essence is the make up of the present day component.

However, in contrast to the results of modern-day techno logy, the proportions of the various bits — and in particular of the jets — were arrived at by a combination of accident and whatever size drill the mechanic had to hand at the particular moment.

What price stoichiometric mixture in 1918?

Petrol economy, even idling and good acceleration were not then considered at all or were deemed refinements to be earnestly hoped for in the dim and distant future or to be discussed long and hard at the local meeting of the I Mech E.

To be fair to the carburettor — which must be considered as the example to end all examples of the engineer's ability to compromise — many of its defects were aggravated by deficiencies in the rest of the vehicle. Excessive vibration for example, owing to a combination of badly balanced moving parts and dubious springing gave rise to fractured pipes and stuck floats and many other annoyances.

At this point in time — to use a familiar phrase — modern heavy lorries have a reasonably rigid chassis and very flexible springs. In the years before WW1 the converse was true in that most of the flexibility was provided by the chassis. The springs were there merely as a con venient way of attaching ti axles to the frame. Damper Who mentioned dampers?

Thus it can be seen that 01 of the major problems fach both the designer and the fie engineer was vibration. Apa from upsetting the delica constitution of the carbure tor, it was often responsible fi the rapid loss of cooling wat (Magirus Deutz owners nh leave at this point) whic sometimes led the uninitiat( to ponder whether the passir vehicle was steam or petr powered — a steady stream boiling water down the midd of the road was apt to be co] fusing.

A glance at a veteran of ti road with its yards of fragi tubing makes one wonder the concept could possibl hold water (sorry) for mo] than a mile or so, but there a] still several such machines St mobile today to prove th practice can sometimes equ theory.

Clutch maintenance ar durability are two are which, although impravE considerably over the year still cause the fleet engineer lot of aggravation. Consid Droblem of the designer in early days of ic engine ered lorries.

though he was not reqd to deal with a multity of lb ft (what's a Newmetre?), what torque was lable had to be transmitthrough leather and metal ie most satisfactory clutch erials available at the time. le clutches of the day were he cone type — in some ,s a misnomer as the ing surface was only part projected cone (see the )mpanying diagram). One of the clutch was formed he actual rim of the flywwhile the other consisted • casting to which was_fas K1 a lining of leather.

ecause of the coefficient of :ion (around 0.3) and the lparatively small lining very heavy springs were essary to prevent clutch which meant that the • ers ended up with a left leg -1 the proportions of a cart se. This heavy pressure lpressed the leather con Tably, and it was never a sfactory remedy for clutch Indeed, taking up the re with such a clutch left air filled with an aroma of rol and well-done rump tk.

>rivers of F10 Volvos with ir multiplicity of gearbox os would not have enjoyed mselves 60 years ago. Most the early designs boasted three gears and the accuy of their cutting (or rather lack of it) made them ex-nly noisy in operation.

'he boxes themselves ded to be on the large side isidering the comparatively all number of cogs inside.

s was due to the selection chanism which employed y one set of sliding gears, ich moved from one end of box to the other in passing m one end of the box to the ter.

n turn this necessitated exmely long shafts and no 11-defined neutral position.

practice, however, the s-skilled driver could often d himself on a steep hill with >oxful of neutrals and no as.

dany gearbox failures could laid at the door of faulty irication. Lubrication sys'is in 1918 tended to be of ,"pour enough oil in and it'll alright" type, but designers re not yet appreciative of need to provide the trbox with an air-vent. Thus the heat generated during running caused excessive pressure which forced the air out past the seals and bearings.

Owing to the prevalence of chain drive, most early gearboxes also incorporated the differential gears with the combined assembly being housed in the same casing and the drive shafts being extended on either side to carry the chain sprockets outside the frame.

Again this was a reasonably sound idea in principle, but less so in practice. The outer ends of these drive shafts were carried in separate housings bolted to the side members which was fine, provided the chassis didn't flex. But it quite often did, causing tremendous problems to the operator with broken shafts and binding bearings. Housing the drive shafts in a casing which was fixed rigidly to the gearbox solved this problem.

Extending the design of a bicycle to provide the transmission for a heavy lorry was not a good idea. The torque transmitted by four lusty cylinders firing once every lamp-post was somewhat higher that that provided by a pair of legs. Thus the chains often took the path of least resistance twisting themselves into graceful spirals in their praiseworthy efforts to get the lorry up the hill.

The preceeding commetns have all assumed that propulsion was solely by mechanical means.

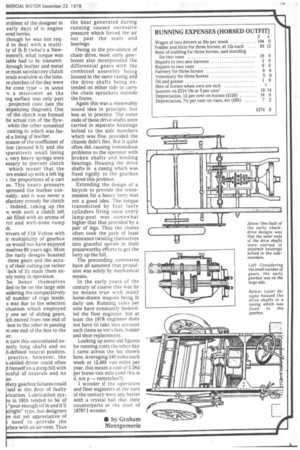

In the early years of the century of course this was by no means true with many horse-drawn wagons being in daily use. Running costs per mile have constantly bedevilled the fleet engineer, but at least the 1978 engineer does not have to take into account such items as vet's fees, fodder and shoe replacement.

Looking up some old figures for running costs the other day I came across the list shown here. Averaging 240 miles each week or 12,480 van miles per year, this meant a cost of 5.28d per horse-van mile (and this is d, not p — remember?).

I wonder if the operators and fleet engineers at the turn of the century were any better with a crystal bail that their counterparts at the start of 1979? I wonder.

0 by Graham Montgomerie