BMC Mastiff 16-ton-gross truck

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

Page 54

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

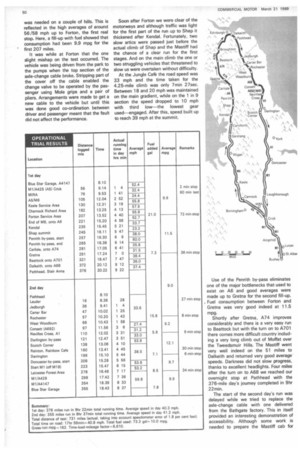

by A. J. P. Wilding, MIMechE, MIRTE PROOF that a high power-to-weight ratio does not necessarily result in poor fuel consumption has been given by many CM road tests in the recent past. But never more convincingly than in our test of the new BMC 16-ton-gross four-wheeler: 731 miles from Hemel Hempstead to Dalkeith and back in 18hr at an average running speed of almost 41 mph and a fuel consumption of exactly 10 mpg—this was the impressive record put up by the new model on a full CM operational trial.

The Mastiff showed itself a first-class vehicle in other respects, too. Very good braking figures and acceleration times were produced and it was most pleasant to drive. Seating was comfortable and there was a relatively low level of noise in the cab, while the general handling characteristics were as good as on any truck I have previously driven.

With the Perkins V8 engine giving 179 bhp there was, if anything, a surfeit of power by present-day standards. A higher axle ratio or an overdrive gearbox would have been a proposition—and probably have given an even better fuel return—and this was illustrated when the test vehicle completed the whole 132-mile southern stretch of M1 without a downward change in the gearbox!

As well as the operational trial a full normal road test was carried out, and on neither was there the slightest sign of trouble from the vehicle except for a small problem with the control cable for the ratio change of the two-speed axle.

Full details of the Mastiff were given in last week's issue, from which it will have been seen that the chassis has a straightforward specification with virtually no variations available from the standard design—in the case of the rigids the only options are in respect of axle type and ratios and the type of gearbox used with the particular axle fitted. The 179 bhp output of the Perkins V8.510 relates to the BS AU 141 gross standard and is produced at 2,800 rpm. Maximum gross torque to the same standard is 398 lb.ft at 1,600 rpm.

The drive from the engine to the Eaton Yale and Towne synchromesh gearbox is through a 12in. twin-plate clutch with a new design of Clayton Dewandre air/hydraulic servo called the HM. The master cylinder is pedal-operated, and the HM servo operates directly on to the clutch lever. The force supplied to the clutch mechanism is always related to that exerted at the pedal, the air pressure being determined by the hydraulic pressure from the master cylinder. If the air supply fails, hydraulic pressure alone operates the clutch.

This new system worked very well on the test and was markedly better than the former air-assisted clutch used by BMC on the FJ. The clutch was light to operate, needing about 45Ib pressure and there was no delay in transmission of the movement of the pedal to the clutch. Similarly there was no sluggishness on the return stroke, so that the whole "feel" was that of a direct mechanical linkage.

As the test vehicle had the optional two-speed axle—with the higher ratios of 5.57 /7.6 to 1 —the SME version of the Eaton Yale and Towne five-speed gearbox was fitted. The spacing of the ratios in this unit is closer than in the box used with the single-speed axle to give better progression in conjunction with the two-speed axle. With this set-up there are 10 distinct forward ratios, as the maximum speeds in the gears (quoted in the table) show. But it will be seen that for progression, the change sequence is "low" and then "high" ratio in the axle up to third gear and then fourth low, fifth low followed by fourth high and fifth high.

This change pattern is not novel and has advantages in that two of the three changes using top and fourth are mechanical. I find that the change characteristics of two-speed axles vary so much from one vehicle to another that until absolutely used to a particular chassis

there is often a gamble on whether the axle will change perfectly.

The axle change on the test Mastiff was not very good and rather inconsistent. The ratio change was reasonable in lower gears but sluggish when in top and fourth. It was particularly slow when made in conjunction with a downward change (from fourth/high to fifth/low)—so much so that on the steeper gradients, by the time fifth/low was engaged, a further change to fourth/low was called for almost immediately. It was therefore better to omit fifth/low in the downward sequence As is usual with synchromesh gearboxes in heavy vehicles, the gear-change action was on the heavy side but the lever on the Mastiff is well placed and there was no awkwardness; the very good design of clutch operating system helped to keep effort down.

The braking characteristics of the Mastiff in general driving were also praiseworthy. There was good response to

vernent of the treadle, while balance ween front and rear was excellent. 3 latter point was confirmed on the ke tests. Those on normal roads were a slightly damp surface and, as a ck, repeat tests were made at the tor Industry Research Association cir: at Nuneaton during the operational I. In spite of the damp surface, excel: figures were obtained on the early :s and there was very little wheel eing—a maximum of about 6ft from offside rear on one stop. The MIRA :s on a dry surface showed stopping ances that were almost identical. In : the Mastiff results were better than

previously recorded by CM on a ton-gross four-wheeler. The same aps to the acceleration times, particular'or the direct-drive runs, confirming higher axle ratios would be practici.

et-route consumption checks were le on A6 and M1 south of Luton and le the figure obtained on the motor

, run-9.7 mpg—was confirmed on operational trial, the 10.2 mpg for the test was rather lower than we ieved on other similar sections of A6 Al. But the vehicle had covered only 10 miles at the time of the initial s, while there was over 5,000 miles the clock at the start of our long run. peat test on A6 at Luton would, I am !, have returned a consumption close 1.5 mpg.

or all the tests the Mastiff grossed 3.75cwt over the legal 16-ton limit, this excess being accounted for by an extra man in the cab and various items of equipment carried for the tests. The chassis carried a fairly heavy timber platform body. Chassis/cab kerb weight (including the full fuel tank, spare wheel, etc.) was 4 tons 16.5cwt so it is safe to assume that with a light alloy body a payload of around 10 tons 12cwt would be possible instead of the 10 tons 9cwt actually carried.

It was clear right from the start of the operational trial that the Mastiff was going to romp over the route. The only downward gear-changes needed on the first section of motorway—to Crick --were the result of baulking by other traffic and a speed of between 60 and the maximum of 65 mph was maintained for most of the way. Traffic on the first part of A5 up to MIRA was light, allowing most of this stretch to be made at the legal maximum of 40 mph but after MIRA (and the hour of testing) traffic was heavy and there was a considerable blockage due to roadworks in Wilnecote. A quarter of an hour spent in creeping for more than a mile brought the average for the section to A6 down by 6 mph. The towns on this second part of A5 usually result in a reduced average but the difference would not in normal circumstances be more than 2 mph.

Once on M6 it was again only the traffic that really slowed the vehicle and, at the most, a single downward change was needed on a couple of hills. This is reflected in the high averages of around 56/58 mph up to Forton, the first real stop. Here, a fill-up with fuel showed that consumption had been 9.9 mpg for the first 207 miles.

It was while at Forton that the one slight mishap on the test occurred. The vehicle was being driven from the park to the pumps when the top section of the axle-change cable broke. Stripping part of the cover off the cable enabled the change valve to be operated by the passenger using Mole grips and a pair of pliers. Arrangements were made to get a new cable to the vehicle but until this was done good co-ordination between driver and passenger meant that the fault did not affect the performance. Soon after Forton we were clear of the motorways and although traffic was light for the first part of the run up to Shap it thickened after Kendal. Fortunately, two slow artics were passed just before the actual climb of Shap and the Mastiff had the chance of a clear run for the first stages. And on the main climb the one or two struggling vehicles that threatened to slow us were overtaken without difficulty.

At the Jungle Café the road speed was 33 mph and the time taken for the 4.25-mile climb was only 7min 27sec. Between 18 and 20 mph was maintained on the main gradient, while on the 1 in 9 section the speed dropped to 10 mph with third low-the lowest gear used-engaged. After this, speed built up to reach 39 mph at the summit. Use of the Penrith by-pass eliminates one of the major bottlenecks that used to exist on A6 and good averages were made up to Gretna for the second fill-up. , Fuel consumption between Forton and Gretna was very good indeed at 11.5 mpg.

Shortly after Gretna, A74 improves considerably and there is a very easy run to Beattock but with the turn on to A701 there comes more difficult country including a very long climb out of Moffat over the Tweedsmuir Hills. The Mastiff went very well indeed on the 51 miles to Dalkeith and returned very good average speeds. Darkness did not slow progress, thanks to excellent headlights. Four miles after the turn on to A68 we reached our overnight stop at Pathhead with the 376-mile day's journey completed in 9hr 22min.

The start of the second day's run was delayed while we tried to replace the axle-change cable with one delivered from the Bathgate factory. This in itself provided an interesting demonstration of accessibility. Although some work is needed to prepare the Mastiff cab for g, it turned out to be no trouble at all only half an hour elapsed between ing the job and setting off on the road n. And this time included taking the le cover out to see if we could reach aide-change valve without going igh the tilting procedure. We could and then spent more time trying to sten the Allen screw holding the ating wire with various tools except right size of key which we did not II A further stop was made at Lauder omplete the repair with a borrowed key, and everything was all right n.

afore the next planned stop at Ro;ter, we went over Carter Bar which climbed in fine style. With the speed over 40 mph at the bottom, only 58sec was needed for the 1.85-long climb. For most of the gradient ch has a slope of 1 in 13/14) the id was between 22 and 25 mph with th/low and third /high engaged. On steepest, 1 in 10, part near the top speed dropped to 20 mph in third!

and then quickly built up to reach nph at the summit.

he fuel used between Gretna and hester showed that exactly 9 mpg been achieved—not bad considering terrain and the good average speeds.

better was the 9.2 mpg for the very part of A68 and the short stretch Consett to Al. A check made for worst 26 miles of A68 showed 8 and this suggests that speed had more effect on the consumption of the Mastiff than hard work.

Among the hardest work the Mastiff had to tackle on the test was the climb of Riding Mill on A68 which, although not very long-0.6 miles—is very steep with a 1 in 5 gradient at the worst part. But it proved no trouble for the Mastiff, which completed the climb in 2min 21sec with second /low needed for the steepest part, where minimum speed was 10 mph. The severe gradients of A68 were not expected to bring any problems because the vehicle had been tested on the set slopes at MIRA. It climbed the 1 in 3 in first/low, and restarts in this gear and reverse /low were completed on the 1 in 4 gradient. On the 1 in 6, which is the most severe hill normally used for truck testing by CM, restarts were possible in second /low. The most notable thing about the run on Al was the amount of goods traffic passing us while we ambled along with the speedometer needle hovering on the 40 mph mark. At this rate of travel the noise level in the Mastiff cab was very low and fuel consumption at 12.1 mpg was excellent.

With 206 miles covered we started what always seems the final run home, for although there are 149 miles of motorway from the start of the Doncaster by-pass to the end of the test most of the effort is over. The Mastiff made light work of the long "drag" of M18 and although the part of MI north of Crick has some pretty severe gradients the whole run was made in top gear. The gradients kept the average speed down but after Leicester Forest the average to the A4147 turn-off was only a fraction below 60 mph.

• At the Blue Star Garage just off the motorway the fuel tank was filled with the vehicle in exactly the same spot as when the tank was topped up at the start of the test. The 7.8gal added brought the total used over the 731 miles to 73.3gal, and it would be hard to get nearer 10 mpg than that! Average speed on the second day was 41.2 mph and with a total time on the road just lmin short of 18hr, overall average speed was 40.8 mph.

My main impression of the Mastiff after all the testing is of a robust vehicle, safe and easy to handle and well up to present-day standards both mechanically and in respect of cab furniture and furnishings. The 731-mile journey was not unduly tiring, a factor largely due to the low noise level in the cab and also to comfortable seats. At 40 mph, normal conversation was possible and although there was more noise at over 60 mph it was never bothersome.

I have already referred to the clutch and brake controls and the accelerator was also light for most of its travel; there was an increase in effort needed for the last quarter inch or so which made holding full throttle for long periods fairly tiring.

The driving position was very good, helping forward visibility, while the wipers cleared as much of the screen as was necessary. On the initial tests, both outside mirrors had flat glasses which did not in my opinion give an adequate view to the rear and at my request the offside one was changed for a convex type for the long run. This was very good indeed but the nearside unit which was not changed was quite inadequate and of limited use. No rain fell during the test so it was not possible to say if the positioning of the mirrors would result in them getting dirty but this is not likely as they are set back from the cab front. This positioning led to the disadvantage that a 75deg turn of the head was needed to look into them and it would be better if the brackets could be angled forward so that the mirrors could be viewed through the quarter-lights. I thought the detachable steady-brackets a very good idea.

Plenty of room is provided for papers, with cubby holes in the dash and a pocket in the nearside door.

Suspension was excellent and well damped and the steering design was also very good. This was especially so on motorways, although on twisting roads one had a tendency to over-correct. Nevertheless, the degree of assistance was just right and for the whole of the travel the "feel" had the right relation to the weight of the vehicle.

Taken all round, a very successful test result.

Basic price of the test vehicle is £2,700 in chassis/cab form.