COMER 13-TON-GROSS FOUR-WHEELER

Page 40

Page 42

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IN COMMON with other British manufacturers of mediumweight goods chassis the Rootes Group has made alterations in gross weight ratings of its current models in anticipation of the start of plating next January. Increases in weight limits have been small in general and they have been more than justifiable in most cases because this class of vehicle commonly has been overloaded —often to the legal limit—and with plating, the maximum figure put on chassis will have to be adhered to if the chance of new higher penalties being incurred are to be avoided.

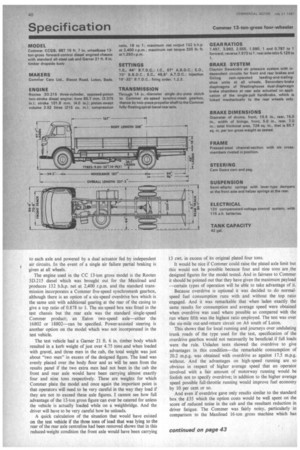

A typical chassis in this context has been the Commer 8--tonner which carried a maximum rating of 12.5 tons and has now been re-rated for 13 tons gross. It is not to be expected that a weight increase of 10 cwt. would have any serious affect on performance, braking and so on and a full road test confirmed that at 13 tons gross the Commer CC model has brakes well able to cope with the weight, comfortably exceeding the minimum requirements of the latest Construction and Use Regulations. General performance was at a high standard and one of the most important features of the test results was fuel consumption, excellent figures being obtained.

The Commer CC range is the successor to the CA and CB 8-tonners which were built from 1962 to 1965. These three chassis types have the Rootes three-cylinder opposed-piston two-stroke diesel and current counterparts are the VA and VB chassis which have Perkins 6.354 diesels. The Standard List to be issued by the Ministry of Transport detailing the weights at which existing goods vehicles will be plated will almost certainly give the figure of 13 tons g.v.w. to all the chassis mentioned in this paragraph but there will be a proviso that the 1962/1965 CA and CB will have to have a handbrake booster conversion to attain the high weights.

The reason for this is that in 1965 when the CC, VA and VB were introduced the brake system was changed from a straightforward air-assisted hydraulic layout to a split system which complies with the mainand secondary-brakes in the latest regulations. From October 1965 a full air-pressure system was introduced as an alternative and this was employed on the test vehicle. A similar layout to that on the Maxiload 16-ton-gross model is used with the brakes to the front and rear axle on separate circuits and assistance given to handbrake application through the secondary sides of double-diaphragm chambers at the rear.

The standard brake system is an air-hydraulic design with a tandem master cylinder feeding independent hydraulic circuits to each axle and powered by a dual actuator fed by independent air circuits. In the event of a single air failure partial braking is given at all wheels.

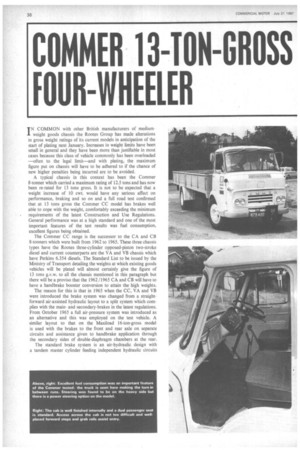

The engine used in the CC 13-ton gross model is the Rootes 3D.215 diesel which was brought out for the Maxiload and produces 132 b.h.p. net at 2,400 r.p.m. and the standard transmission incorporates a Commer five-speed synchromesh gearbox, although there is an option of a six-speed overdrive box which is the same unit with additional gearing at the rear of the casing to give a top ratio of 0.878 to 1. The six-speed box was fitted in the test chassis but the rear axle was the standard single-speed Commer product; an Eaton two-speed axle—either the 16802 or 18802—can be specified. Power-assisted steering is another option on the model which was not incorporated in the test vehicle.

The test vehicle had a Garner 21 ft. 6 in. timber body which resulted in a kerb weight of just over 4.75 tons .and when loaded with gravel, and three men in the cab, the total weight was just about "two men" in excess of the designed figure. The load was evenly placed over the body floor and as will be seen from the results panel if the two extra men had not been in the cab the front and rear axle would have been carrying almost exactly four and nine tons respectively. These are weights for which Commer plate the model and once again the important point is that operators will need to be very careful in the way they load if they are not to exceed these axle figures. I cannot see how full advantage of the 13-ton gross figure can ever be catered for unless the vehicle is actually loaded while on a weighbridge. And the driver will have to be very careful how he unloads.

A quick calculation of the situation that would have existed on the test vehicle if the three tons of load that was lying to the rear of the rear axle centreline had been removed shows that in this reduced-weight condition the front axle would have been carrying 13 cwt. in excess of its original plated four tons.

It would be nice if Corn mer could raise the plated axle limit but this would not be possible because four and nine tons are the designed figures for the model tested. And in fairness to Commer it should be pointed out that they have given the maximum payload —certain types of operation will be able to take advantage of it.

Because overdrive is optional it was decided to do normalspeed fuel consumption runs with and without the top ratio engaged. And it was remarkable that when laden exactly the same results for consumption and average speed were obtained when overdrive was used where possible as compared with the run where fifth was the highest ratio employed. The test was over the six-mile out-and-return circuit on A6 south of Luton.

This shows that for local running and journeys over undulating trunk roads of the type used for the test, specification of the overdrive gearbox would not necessarily be beneficial if full loads were the rule. Unladen tests showed the overdrive to give advantages in this condition—the remarkable consumption of 20.2 m.p.g. was obtained with overdrive as against 17.5 m.p.g. without. And the advantages on high-speed running are so obvious in respect of higher average speed that an operator involved with a fair amount of motorway running would be foolish not to specify overdrive; in addition to the higher average speed possible full-throttle running would improve fuel economy by 10 per cent or so.

And even if overdrive gave only results similar to the standard box the £35 which the option costs would be well spent on the score of reduced noise in the cab and the resultant reduction in driver fatigue. The Commer was fairly noisy, particularly in comparison to the Maxiload 16-ton gross machine which has more lagging in its "super-luxury" version of the same basic cab used on the model tested. It was noticeably quieter on the runs employing overdrive than on those without it.

Acceleration-test results were well up to the standards expected of this type of chassis and better than most chassis previously tested carrying payloads of around eight tons. The direct-drive figures were not so good but at 10 m.p.h. in directdrive (rear axle ratio was 5.125 to 1) the engine was running at less than idling speed and the pull-away was rather difficult until about 13 m.p.h. when the runs started to get a bit smoother. The through-the-gears runs were helped by well-spaced ratios. Maximum speeds in the gears were 9, 15, 22, 35, 54 and 68 m.p.h. and it is worthy of note that the speedometer was accurate at all speeds.

Braking tests produced excellent figures as will be seen from the table. The stopping distances for maximum-pressure stops can be resolved to overall efficiencies of 52.5 and 55 per cent respectively from 20 and 30 m.p.h. and these compare with Tapley meter readings, for maximum deceleration on the stops, of 67 per cent from 20 m.p.h. and 66 per cent from 30 m.p.h., showing that there was minimum delay between first hitting the pedal and the application of the brake shoes to the drums.

There was no marking of the road by any of the tyres on these maximum pressure stops and application of the handbrake alone did not result in driving-axle wheel locking. The handbrake test also gave a check of one circuit of the brake system-the rear-and to check the efficiency given by the circuit to the front wheels, the rear-brake reservoir was exhausted and the front brakes on their own gave a Tapley-meter reading of 31 per cent. Tyre marks were left on the road in this last test-by the nearside front wheel-but they were only light, showing that the wheel had not locked. As on the other stops the Commer was perfectly stable.

The Commer put up a good performance on the tests on Bison Hill, detailed results of which can be seen in the accompanying table. Downward gear changes gave no trouble but on an initial run up the hill, a change from first to second just after the steepest section was muffed due, in my opinion, to an imprecise second-gear position in the "gate" and this made a second run necessary. A relatively wide gap between first and second was

noticeable-peak revs in first equalled an engine speed in second well below that giving useful torque-so on the second run first was kept in engagement for a much longer period and until a less severe gradient was reached, even though the engine was running at maximum revs for most of the time-in first.

The brake fade test showed that the Commer should not be troublesome on this score and handbrake-holding and stop-andrestart tests were satisfactory, although difficulty in knowing when the handbrake was released caused a little trouble when starting off up the hill.

Driving the Commer was quite a pleasant experience. I have already mentioned that the noise inside the cab was at a higher level than was the case with the Commer Maxiload (with the same engine and transmission) that I had tested, but the driving position was good and controls well-placed. The steering felt rather heavy and I can see the time when power steering will be standard even on this class of goods vehicle because the increased effort required, even with a four-ton axle load, is so much greater than with current power steering layouts on maximum-gross jobs. As well as giving very good stopping distances, the brake system was good from the application-character angle, there being a light pedal yet with adequate feel when unladen.

At high speeds extra care had to be taken to keep the vehicle on course and there was some "bouncing" of the front end when running between 47 and 50 m.p.h. on the bumpier sections of MI-a surprising phenomenon as the suspension was perfectly smooth above and below these speeds.

The basic price of the chassis as tested is £1,945 and the cost of options as fitted are:-overdrive gearbox £35; full-air brakes £75; heater, £18; 42 gal. fuel tank in place of the standard 30 gal., £4 5s. Other options available on the model are power steering which costs £55, 24 V electrics, £50 10s. and the two Eaton two-speed axle options cost £120 for the 16802 and /215 for the 18802.