ScammeIVORSL Crusader 32-ton-gross attic

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Trevor Longcroft

pictures by Harry Roberts

IN a sense every commercial vehicle is built :o meet customers' requirements, or what nanufacturers believe their requirements to 3e, but seldom does an individual operator 13ave the chance to specify a vehicle virtually from the drawing board up. This Oyes a special interest to our recent :txclusive test of the new 4 X 2 version of the Scammell Crusader built for British Road Services Ltd because in this case the nitiative for this particular model came rom BRSL, who were seeking a tough, .eliable "premium" vehicle for high-intensity runking.

So this Crusader is very much an 'operator's vehicle" and although it is mpossible in a relatively short trial to valuate the reliability and longevity of a truck, the Crusader certainly gave the impression of being a tireless long-distance runner—especially on motorways, where it will presumably spend much of its life. But off the motorways, especially on the hillier main roads of the North, it needed the very low crawler gear fairly frequently, while backache at the end of several hours at the wheel suggested that more support in the small of the back would make this a more suitable trunk vehicle from the driver's point of view.

The vehicle that we tested was a BRSL prototype, but a 4 x 2 Crusader is to be produced for general sale later this year and will differ in some respects, though the chassis will follow the same general lines as this long-wheelbase BRSL tractive unit. For the test the unit was coupled to a 33ft ScatruneII tandem-axle semi-trailer and the outfit was run at maximum gross weight; in fact it proved to weigh 32 tons 7cwt with driver, observer and test equipment aboard.

CM has had two opportunities to assess this prototype, the first occasion with a load of paper reels on a Taskers trailer as part of an exercise for our Fleet Management Conference, when it grossed only about 25 tons, and on the second occasion with the Scanunell trailer, running at maximum gross, as above.

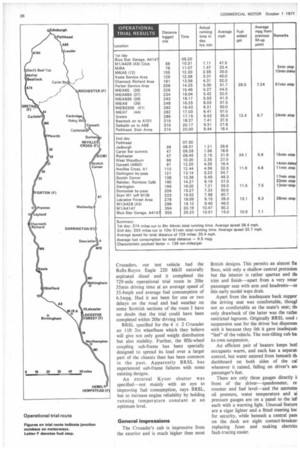

Like most of the first batch of BRSL Crusaders. our test vehicle had the Rolls-Royce Eagle 220 Nan naturally aspirated diesel and it completed the 729-mile operational trial route in 20hr 35min driving time at an average speed of 35.4mph and average fuel consumption of 6.5mpg. Had it not been for one or two delays on the road and bad weather on some Scottish sections of the route I have no doubt that the trial could have been completed within 20hr driving time.

BRSL specified for the 4 X 2 Crusader an lift 3in wheelbase which they believe will give not only good weight distribution but also stability. Further, the fifth-wheel coupling sub-frame has been specially designed to spread its load over a larger part of the chassis than has been common in the past. Apparently BRSL has experienced sub-frame failures with some existing designs.

An external Kysor shutter was specified-not mainly with an eye to improving fuel consumption, says BRSL, but to increase engine reliability by holding running temperature constant at an optimum level.

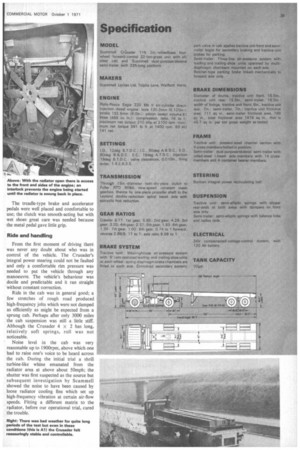

General impressions The Crusader's cab is impressive from the exterior and is much higher than most British designs. This permits an almost fla floor, with only a shallow central protusion

but the interior is rather spartan and thi trim and finish-apart from a very smar passenger seat with arm and headrests-or this early model were drab.

Apart from the inadequate back suppor the driving seat was comfortable, thougl not so comfortable as the mate's seat; thi

only drawback of the latter was the rathe restricted legroom. Originally BRSL used g

suspension seat for the driver but dispense( with it because they felt it gave inadequat "feel" of the vehicle. The non-tilting cab ha its own suspension.

An efficient pair of heaters keeps botl occupants warm, and each has a separat control, but water entered from beneath th dashboard on both sides of the cal whenever it rained, falling on driver's aril passenger's feet.

There are only three gauges directly front of the driver-speedometer, re counter and fuel level-and the ammeter oil pressure, water temperature and ai pressure gauges are on a panel to the lefl each with a warning light. Unusual feature are a cigar lighter and a fitted steering loc for security, while beneath a central path on the dash are eight contact-breaken replacing fuses and making electricl fault-tracing easier. The treadle-type brake and accelerator pedals were well placed and comfortable to use; the clutch was smooth-acting but with wet shoes great care was needed because the metal pedal gave little grip.

Ride and handling

From the first moment of driving there was never any doubt about who was in control of the vehicle. The Crusader's integral power steering could not be faulted and only a comfortable rim pressure was needed to put the vehicle through any manoeuvre. The vehicle's behaviour was docile and predictable and it ran straight without constant correction.

Ride in the cab was in general good; a few stretches of rough road produced high-frequency jolts which were not damped as efficiently as might be expected from a sprung cab. Perhaps after only 3000 miles the cab suspension was still •a little stiff. Although the Crusader 4 x 2 has long, relatively soft springs, roll was not noticeable.

Noise level in the cab was very reasonable up to 1900rpm, above which one had to raise one's voice to be heard across the cab. During the initial trial a shrill turbine-like whine emanated from the radiator area at above about 50mph; the shutter was first suspected as the source but subsequent investigation by Scammell showed the noise to have been caused by loose radiator cooling fins which set up high-frequency vibration at certain air-flow speeds. Fitting a different matrix to the radiator, before our operational trial, cured the trouble. In an effort to direct spray and dirt away from the cab glasses and mirrors, deflectors are fitted on the windscreen pillars. On the first exercise the cab remained clean, and the mirrors reasonably so, but rain was deposited on the inside of the screen when the quarter-lights were open. On the later trial we did not encounter this problem.

Braking and acceleration

The Fuller RTO 909A nine-speed range-change gearbox has been specified by BRSL for the Crusader 4 x 2 and has a torque capacity sufficient to cope with the 265bhp turbocharged Eagle when this is Fitted. The overdrive version of the Fuller box has well-spaced ratios and all nine gears were put to good use on the operational trial. Gearchanging was completed with little fuss, and the works driver and I rarely missed a gear.

The air-operated range change between fourth and fifth gears was smooth and positive, but might even have been improved with a neater operating switch.

Brakes on the Crusader proved adequate, but by no means outstanding. Full-pressure stops at MIRA, for example, produced stopping distances of 71.75ft from 30mph and 32.4ft from 20mph—figures which I feel could be improved upon. On the full-pressure stops there was no consistency in the way the wheels locked—on one occasion the front offside wheel and, the driving axle wheels left black marks. On the road, however, we were never conscious of any brake inadequacy at maximum gross weight.

The secondary brake, operating on the tractive unit front axle and trailer bogie, returned a 40 per cent efficiency reading on the Tapley meter from 20 mph. The handbrake was able to hold the laden vehicle in both directions on a 1 in 5 gradient.

Hill performance and fuel consumption

On motorways 7th gear (direct) and 8th (overdrive) were required for the most part; steepest sections of motorway never needed lower than 5th. But on the severe, hilly sections of A68, for example, hard working of the gearbox was needed to maintain progress and we were down to crawler on many occasions.

Ascending a wet, greasy gradient of about 1 in 7 at Ridsdale first gear had been engaged and the revs were falling, but before a change to crawler could be made we came to a standstill with wheelspin. A restart proved impossible on the slippery slope so we had to reverse to the foot and then made a successful climb in crawler gear. Our most severe climb—Riding Mill—was therefore tackled in crawler from the bottom.

(Wheelspin also hindered a restart on the 1 in 6 test hill at MIRA, but the Crusader eventually managed it after failing several times. In reverse, however, wheelspin defeated us on the 1 in 6,) The A68 gradients called for quick downward changes and on the more severe hills, with revs dropping quickly, it might have been better to drop two gears at a time. On the occasions when crawler was needed, the movement across this part of the gate took a little longer than the other gearchanges.

Fuel consumption for the complete trial was 6.5mpg, this figure being among the best obtained by us for 32-ton-gross outfits on this test route. Motorway consumption was respectable, considering the good average speeds maintained; in many instances the Crusader was running near the 60mph limit for sustained periods. The 4.6 mpg figure obtained for the Rochester to Nevilles Cross section indicates the amount of low gear work necessary here.

But, as remarked before, this new model is intended mainly for motorway trunking and, as such, appears to offer a good blend of economy and performance. Our test vehicle was a very early example, and no doubt further development work will refine the product and eliminate some of the points we found to criticize.