TESCO GOES EST

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 73

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

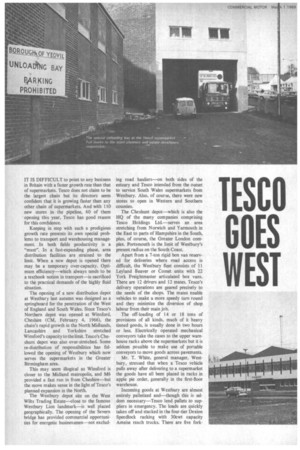

IT IS DIFFICULT to point to any business in Britain with a faster growth rate than that of supermarkets. Tesco does not claim to be the largest chain but its directors seem confident that it is growing faster than any other chain of supermarkets. And with 110 new stores in the pipeline, 60 of them opening this year, Tesco has good reason for this confidence.

Keeping in step with such a prodigious growth rate presents its own special problems to transport and warehousing management. In both fields productivity is a "must". In a fast-expanding phase, area distribution facilities are strained to the limit. When a new depot is opened there may be a temporary over-capacity. Optimum efficiency—which always tends to be a textbook notion in transport—is sacrificed to the practical demands of the highly fluid situation.

The opening of a new distribution depot at Westbury last autumn was designed as a springboard for the penetration of the West of England and South Wales. Since Tesco's Northern depot was opened at Winsford, Cheshire (CM, February 4, 1966), the chain's rapid growth in the North Midlands, Lancashire and Yorkshire stretched Winsford's capacity to the limit. Tesco's Cheshunt depot was also over-stretched. Some re-distribution of responsibilities has followed the opening of Westbury which now serves the supermarkets in the Greater Birmingham area.

This may seem illogical as Winsford is closer to the Midland metropolis, and M6 provided a fast run in from Cheshire—but the move makes sense in the light of Tesco's planned expansion in the North.

The Westbury depot site on the West Wilts Trading Estate—close to the famous Westbury Lion landmark—is well placed geographically. The opening of the Severn bridge has provided commercial opportunities for energetic businessmen—not exclud

ing road hauliers—on both sides of the estuary and Tesco intended from the outset to service South Wales supermarkets from Westbury. Also, of course, there were new stores to open in Western and Southern counties.

The Che shunt depot—which is also the HQ of the many companies comprising Tesco Holdings Ltd.—serves an area stretching from Norwich and Yarmouth in the East to parts of Hampshire in the South, plus, of course, the Greater London complex. Portsmouth is the limit of Westbury's present radius on the South Coast.

Apart from a 7-ton rigid box van reserved for deliveries where road access is difficult, the Westbury fleet consists of 11 Leyland Beaver or Comet units with 22 York Freightmaster articulated box vans. There are 12 drivers and 12 mates. Tesco's delivery operations are geared precisely to the needs of the shops. The mates enable vehicles to make a more speedy turn round and they minimize the diversion of shop labour from their main job.

The off-loading of 14 or 18 tons of provisions of all kinds, much of it heavy tinned goods, is usually done in two hours or less. Electrically operated mechanical conveyors take the cases to the upper warehouse racks above the supermarkets but it is seldom possible to make use of portable conveyors to move goods across pavements.

Mr. T. White, general manager, Westbury, stressed that when a Tesco vehicle pulls away after delivering to a supermarket the goods have all been placed in racks in apple pie order, generally in the first-floor warehouse.

Incoming goods at Westbury are almost entirely palletized and—though this is seldom necessary—Tesco lend pallets to suppliers in emergency. The loads are quickly taken off and stacked in the four-tier Dexion Speedlock racking with 30cwt capacity Ameise reach trucks. There are five fork truck operators, all trained in recent months.

I asked Mr. White whether Tesco had considered delivering goods to shops on pallets or wheeled containers. He replied, forthrightly, that it would be a wasteful exercise. "With a delivery radius of around 100 miles at maximum it is vital that we make the best possible use of vehicle-carrying capacity. We get about 17+ tons on the larger Freightmaster bodies which are packed tightly to the roof. Any system of palletization or wheeled cages would lose us appreciable volume and would increase our transport costs prohibitively."

The ordering and make-up of supplies at Westbury is a transport manager's dream. Although supermarket managers order goods by value the Westbury ICT punched card equipment provides for both prices and weights to appear on the invoice. If a shop order totals up to, say, 19 tons, the order is reduced to the 14or 18-ton maximum in the office and the balance is delivered subse quently. It is not necessary to put an excess load on the vehicle and then take off the overload.

I understand that a similar system will be introduced at Cheshunt shortly. When Cheshunt was opened in 1959—"the most modern warehouse in Europe"—weight recording equipment was not available. The £500,000 Westbury depot occupies 100,000 sq.ft. and is a highly effective example of a distribution depot of the '60s but today "the most modern . ." label is much more rapidly overtaken by events.

Even so, Westbury will not be outmoded for many years. Its 10-acre site allows for expansion and the additional office accommodation provided (but not yet occupied) is clearly designed for a much larger throughput than is yet called for. The 50 supermarkets now served will increase to 80 or 90 in the next two years. Hence the wisdom of providing room for growth.

Many old stagers in road transport have regretted the virtual demise of mates—apart from special applications. Tesco's policy is to transfer mates to warehouse duties at the age of 21. If a mate wishes urgently to drive he is likely to leave Soon after but if he stays with Tesco he can be considered for a driving job at the age of 25. The firm believes that at this age a more responsible type of driver is obtainable and no younger drivers are employed at Westbury. Mr. White stressed the value of mates in helping drivers to manoeuvre in busy High Street traffic—yet another practical economic consideration reflecting productivity in its widest sense.

Vehicle maintenance with a new fleet has not been a problem at Westbury so far. There is a well equipped maintenance bay and a skilled fitter is employed. Drivers help with routine lubrication but as the work builds up additional maintenance staff will be set on. Major repair jobs are likely to be done at the Leyland depot at Bristol.

The warehouse equipment at Westbury and the ultimate responsibility for vehicle maintenance there rests with Tesco's transport engineer, Mr. D. R. Baker. I was interested to hear his views on current problems in the industry. Like Mr. White, he is very conscious of the need for maxi mizing productivity in the transport and warehouse functions of Tesco, always with the proviso that these functions are subordinate to the main business activity—supermarkets.

Mr. Baker is also responsible for equipment purchasing for the Tesco supermarkets —and this brings him into contact with a huge number of equipment suppliers.

An incidental effect of the Westbury opening, I learned, was that small depots at Sidcup and Eltham had been closed. These two depots had served a Tesco subsidiary in the London area; the work had now been absorbed by the C heshunt warehouse and transport organization.

The size of supermarkets has a great bearing on the cost of the transport opera tion to supply them. Tesco's shops are generally 7,000 to 8,000 sq.ft.—large enough to absorb the contents of one or more Freightmaster box bodies. (The com pany does not contemplate using largerbodied vehicles.) Tesco has always shown the utmost realism in its reaction to traffic congestion problems and it is participating in the current out-of-hours-delivery experi ment in the Greater London area. Naturally it welcomes any local authority initiative in providing exclusive access roads for lorries.

Mr. Baker felt that the firm had no option but to comply with whatever police or local authority restrictions were applied to super market deliveries in congested High Streets. This was a hazard of the business, to be faced squarely. But he stressed that Tesco's own warehouse deliveries were only part of the problem since about 60 per cent of supermarket supplies were delivered direct by the manufacturers or their carriers. In general, the heaviest and most bulky items were warehoused and delivered by Tesco.

Included in the Tesco warehousing and transport operations is the rapidly increas ing tonnage of HomeN'Ware or non-food items. This part of the merchandising operation has its own warehouse and 16-vehicle fleet at Cuffley, Herts, and is shortly moving to larger premises at Harlow. Ford D800 units with drop frame trailers are used.

The 160,000 sq.ft. Cheshunt warehouse serving about 240 supermarkets operates 27 tractive units in the 20-28 ton g.v.w. category, with 54 Freightmaster semi-trailers. Three rigid vans cope with stores with a difficult access. In a busy week up to 2,000 tons of supplies are delivered.

Good fitters are not readily obtainable at Cheshunt but, so far as the staff situation permits, an increasing proportion of major repairs are undertaken. Mr. Baker firmly believes that equipment is cheaper than men and the well equipped workshops prove his point. Every operator, he suggests, should endeavour to increase his maintenance facilities. He points out that maintenance costs when outside repairers are used are increasing steadily though quality of workmanship is often unsatisfactory. Tesco is progressively carrying out brake conversions to meet the higher standards but it has not always been able to get sets of parts promptly.

Mr. Baker is not a doctrinaire believer in an elaborate maintenance costing system. He accepts that transport managers need to watch costs carefully to see if transport is costing more than it should but he insists —as do most own-account operators— that the profitability of the whole business is the first consideration.

It seems a fair conclusion that transport productivity for many C-licensed operators must be judged in the context of overall productivity. Some firms' operations lend themselves to more intensive vehicle operations than others. Within the context of supermarket warehousing and delivery operations, Tesco, I suggest, is highly productive in the economist's sense----for a given input of resources there is a large output in terms of stock turnover and customer satisfaction. The routine manner in which new stores are opened with clockwork regularity proves the point.