This Formula Approa ection

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

Page 69

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IN F. MOON, A.M.I.R.T.E. IN the same way that there are some operators who are not happy with a vehicle unless it is grossly over-loaded, so there are hauliers who still believe that the greatest operating economy stems from the use of the smallest available engine. We have all followed the inevitable combination of these two dogmas—usually shrouded in smoke at about 2 m.p.h. up a meagre but narrowMainroad hill.

It is always a pleasure, therefore, to be able to test a vehicle which is never likely to get out of breath, the more so if it can cope with an overload of nearly, 40 per cent. without appreciable detriment to the road performance. . When this is accompanied by above-average fuel economy, it is obviou's that the vehicle being tested could be the answer to a lot of operators' problems. When the vehicle is a iledford TK—one of the best commercial vehicles from the driver's angle that has ever been produced—the formula

approaches perfection. , It was rnY pleasure to handle such a combination recently.

the vehicle in question being a Bedford TK 7-tonner fitted with a Perkins 6.354 diesel-engine conversion by Murkett Bros., Ltd., Barkers Lane, Bedford, initial details of this conversion having been given in our issue of July 14, 1961.

Running at the same gross weight as a TK 7-tonner with Bedford 300 diesel tested last year (The Commercial Motor, October 28, 1960) the Perkins-engined TK revealed a gain in fuel economy of just over 14 per cent., whilst with an overload of 2 tons 84 cwt., which brought the test load up to exactly 9 tons, the converted vehicle was under 2 per cent, heavier on fuel than the standard vehicle carrying 6 tons 111 cwt. Similarly, because of the improved power-to-weight ratio, acceleration was about 20 per cent, better in the case of the Perkins-engined Bedford, the comparative figures from a standstill up to 30 m.p.h. being 25.25 seconds and 31.4 seconds. Needless to say, hillclimbing performance showed a proportional improvement.

So much for the performance gains to be expected, but what about the additional initial outlay? Unfortunately the Perkins engine can be installed in the TK only as a conversion, and the price of the 6.354 with compressor and complete with all conversion parts, including a 13-in. clutch assembly, is £440, whilst Murkett's fitting ch £35. Admittedly the allowance on the original B engine might well be up to £200, depending on its tion, but this still leaves an excess of £275 on top basic Vauxhall price of £1,330 for the KFLD extr; wheelbase 7-ton chassis with standard cab and drop-sided body.

Assuming the saving effected by the conversio reduce fuel costs by 0.37d. per mile, a converted would have to cover some 170,000 miles to mem, cost of the conversion in terms of fuel costs alone. is not as black as it sounds, however, for add economies could well stern from the reduced journey times made possible by the more powerful engine, whilst engine life itself should be greater in the case of the Perkins unit as it is fair to say that it is a more solidly built engine than the standard Bedford product, partial evidenceof which is given by its greater weight (94 lb.). Put another way, based on a five-yeardepreciation period and taking into account appropriate income-tax allowances, the cost of the conversion shcitild be recovered in about 24,000 miles per year;

Of course, the additional price of the conversion would he much more rapidly regained in the case of a petrolengined chassis, assuming that the Perkins-engined job could be expected to return a 100 per cent, improvement in fuel economy, whilst in any case the TK 7-tonner plus Perkins-engine conversion (£1,330 ± £275) still costs less than the standard Bedford KGLD 71-ton diesel lorry, the retail price of which is £1673. So all in all the conversion picture is not as bad as it looks, though the position would be considerably better if Vauxhall Motors. Ltd, were to adopt the Perkins 6.354 as one of their factory-fitted optional units.

In contrast to many engine conversions, the installation of the Perkins 6.354 in the Bedford. TK chassis is a surprisingly straight-forward business, helped to a great extent by the simple layout of the Bedford frame and the ample space of the engine compartment beneath the cab seats.

So far as the engine itself is concerned the 12-in, clutch of the Bedford 300 engine is replaced by a 13-in, unit as used with the Leyland 0.350 engine, whilst special frontmounting feet which align with the holes in the existing front engine cross-member (drilled for the Leyland engine installation) are provided.

The standard Bedford bell housing is retained, a 61-in.thick adaptor plate being used to mate with the Perkins clutch housing. This adaptor plate serves a second purpose, incidentally, in that its thickness is such as to align the front-mounting feet longitudinally with the existing frame drillings.

The standard Bedford fan cowl, as used with the Leyland 0.350 installation, has to be added to ensure adequate cooling without having to make use of a larger radiator whilst, because of the greater torque output of the 6.354 compared with the Bedford 300 diesel, the open-ratio gearbox which is standard in 300-engined 7-ton chassis is converted to the same specification as the Bedford close-ratio -box merely by changing two pairs of gear wheels.

The resulting changes in ratio, in addition to raising n7

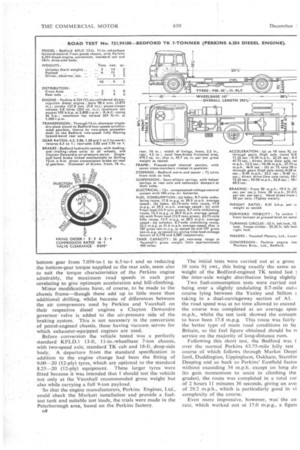

bottom gear from 7.059-to-1 to 6.5-to-1 and so reducing the bottom-gear torque supplied to the rear axle, seem also to suit the torque characteristics of the Perkins engine admirably, the maximum road speeds in each gear corelating to give optimum acceleration and hill-climbing.

Minor modifications have, of course, to be made to the chassis frame-though these add up to little more than additional drilling, whilst because of differences between the air compressors used by Perkins and Vauxhall on their respective diesel engines a Clayton Dewandre governor valve is added to the air-pressure side of the braking system. This is not necessary in the conversion of petrol-engined chassis, these having vacuum servos for which exhauster-equipped engines are used.

Before conversion the vehicle tested was a perfectly standard KFLD.1 13-ft. 11-in.-wheelbase 7-ton chassis, with two-speed axle, standard TK cab and 18-ft. drop-side body. A departure from the standard specification in addition to the engine change had been the fitting of 9.00-20 (12-ply) tyres, which are optional to the standard 8.25-20 (12-ply) equipment. These larger tyres were fitted because it was intended that I should test the vehicle not only at the Vauxhall recommended gross weight but also while carrying a full 9-ton payload.

So that the engine manufacturers, Perkins Engines, Ltd., could check the Murkett installation and provide a fueltest tank and suitable test loads, the trials were made in the Peterborough area, based on the Perkins factory.

D8 The initial tests were carried out at a gross 10 tons 91 cwt., this being exactly the same as weight of the Bedford-erigined TK tested last the inter-axle weight distribution being slightly Two fuel-consumption tests were carried out being over a slightly undulating 8.7-mile out-2 course lying between the Yaxley and Stilton taking in a dual-carriageway section of Al. the road speed was at no time allowed to exceed the course was completed at an average spec m.p.h.. whilst the test tank showed the consum to have been 17.8 m.p.g. This route was fairly the better type of main road conditions to be Britain, so the fuel figure obtained should be rc service on the majority of long-distance runs.

Following this short test, the Bedford was t. over the normal Perkins 63.75-mile hilly test course of which follows through Market Deepi ford, Duddington, Uppingham, Oakham, Stamfor Deeping and so back to Perkins' Eastfield factor without exceeding 34 m.p.h. except on long do (to gain momentum to assist in climbing the grades), the route was completed in a total rur of 2 hours 11 minutes 36 seconds, giving an avei of 29.2 m.p.h., which is particularly good in vi complexity of the course.

Even more impressive, however, was the col rate, which worked out at 17.0 m.p.g., a figurf eptional for the test conditions. (The standard 1 in 1960 gave 15.6 m.p.g. at 28.6 m.p.h. average :r a course less severe than Perkins' 63.75-mile run, tly more hilly than the shorter Yaxley-Stilton running at this same gross weight acceleration, tnd bill-performance tests were conducted. For ard-start acceleration runs, which were timed up %IL, the two-speed axle was left in high ratio and atios of the gearbox were used. The direct-drive de between 10 and 40 m.p.h., were carried out [ow ratio of the axle engaged.. In both cases firstqeration characteristics were revealed, and during t-drive tests the smoothness of both engine and ion when pulling from as low as 8 m.p.h. was ted.

Brakes not Prepared gh the vehicle had in no way been prepared for ests in that the linings had not been deliberately i and the brakes had not been set-up immediately my test, I took braking figures with this vehicle vhen I had tested the other TK 7-tonner last year were wet, whereas on this occasion there was a ) get some idea of the efficiency of the braking a dry roads. The results I obtained merely bore I had suspected since the TK range was introSeptember, 1960: mainly that these brakes are ye average for a mass-production 7-ton chassis. Leasured stopping distances from 20 m.p.h. and were 19.5 ft. and 51 ft. respectively, the maximum )ns indicated by the Tapley meter averaging 82.5

The braking was entirely smooth and unaccomy wheel locking, and good as the figures are, I idea that even shorter stopping distances would en obtained had the _ brakes been checked .ely before my test, as normally happens with ial-vehicle road tests, ind-brake performance from 20 m.p.h. could be to be quite exceptional in view of the use of a ion drum brake mounted on the rear of the gearen I was surprised, however, by the meter figure r cent, which resulted when the hand brake was rom 20 m.p.h. The brake, although very powerful, means fierce and no rear-wheel locking occurred.

s fairly safe to assume that even excessive use of e should not instigate any transmission failures.

ie gradient-performance tests the Bedford was the Dunstable area so that Bison Hill could be ; being the slope normally employed on Bedford is mile long, with an average gradient of 1 in In /ear the standard TK 7-tonner had taken 4 minutes Is to make the climb.

erkins-engined vehicle chopped nearly a minute me, completing the ascent in 3 minutes 37 seconds. lore, the lowest ratio combination needed was ligh, and this was engaged for only 30 seconds, ! standard model had required the use of this same 1 minute 11 seconds.

:unately it was not possible to take cooling-system ures as the TK has a remote header tank, the ure of the water in which bears no relationship mperature in the main cooling circuit. However, ument-panel thermometer needle hardly rose at g the climb, so there was obviously no fear of art test was carried out on the steepest section of 11, the gradient of which is 1 in 61. The handbrake strained the vehicle from rolling back down the several smooth part-throttle restarts were made in bottom-high. No exhaust smoking was observed during these gradient tests.

Having completed the tests at the vehicle-manufacturers' recommended weight limit, the test load was then increased to exactly 9 tons, which brought the gross running weight to 12 ton 18 cwt. with myself, works driver and test gear aboard. The same two fuel-consumption courses were employed and repeat acceleration tests also were carried out.

The additional .2 tons 81 cwt. made nothing like the amount of difference to the performance that might be expected, the consumption over the short route differing by only 2.5 m.p.g. at the same average speed, whilst over the long route the difference was 3.1 m.p.g., the average speed being 1 m.p.h. less, Both these fuel figures are quite remarkable for a vehicle carrying a genuine 9-ton payload, and in view of the severity of the long course the 13.9 m.p.g. figure proves once again the commendable highpower fuel economy of the Perkins 6.354.

As a final fuel test the unladen Bedford was taken round the 8.7-mile run at an average speed of 31.6 m.p.h., and the consumption rate was 22.5 m.p.g. Study of the five sets of fuel figures obtained suggests that operators working between congested urban areas with 7-ton payloads can expect to average 17 m.p.g., whilst working over similar territory with 9-ton loads at least 14 m.p.g. could be expected. This is assuming the vehicle will be laden in each direction: unladen return running will improve these figures to approximately 19.5 m.p.g. and 18 m.p.g. respectively.

Acceleration performance while carrying the 9-ton load was again highly satisfactory, and, as before, there was neither engine nor transmission roughness discernable when making the direct-drive runs. While running at this weight gear speeds were checked using a fifth wheel and these were: first-low, 7 m.p.h.; first-high, 10 m.p.h.; second-low, 15.5 m.p.h.; second-high, 21 m.p.h.; third-low, 27 mph.; thirdhigh, 36 m.p.h.; top-low, 40 m.p.h.; and top-high, 52 m.p.h. With reduced load the maximum speed is about 55 m.p.h.

Power and Quietness

From the driver's angle the two most marked impressions of the Perkins-engined TK were the exceptional pulling power and the low-engine noise. Even when carrying a 9-ton load it was possible to start off on the level in secondlow, whilst the second-high could be used with ease at 10 tons 91 cwt. gross. The top-gear performance was particularly good also, and really a two-speed axle is superfluous, even at nearly 13 tons gross, although intelligent use of the two-speed axle when it is fitted can speed-up hill-climbing, and facilitate overtaking when it might not be wise with a single-speed unit.

So far as noise is concerned, when cruising along a reasonably level stretch of road at about 40 m.p.h. the noise level in the cab is about the same as that likely to be experienced in the upper saloon of a forward-engined double-deck bus, and even when pulling hard the noise is no greater than that inside a single-deck underfloorengined bus. At all times the pitch of the noise is low and so is in no way irritating.

In other respects also the vehicle is a driver's delight. Even with a 9-ton load the steering is light and positive, whilst at both gross weights the suspension was noted to be virtually vice-free. The brakes are entirely adequate without being fierce or needing excessive pedal pressures. In fact the only two valid criticisms that I have are that the changing of the air-operated two-speed axle mechanism Still tenth to be sluggish (I complained about this last year), whilst the action of the gear lever is a bit woolly, particularly where reverse is concerned. Otherwise 1 cannot speak too highly of this Perkins-engined TK. If only Vauxhall's would install the 6.354 themselves. . . .