Productivity in the bus industry

Page 80

Page 81

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

In Great Britain politicians, trade unions and a number of economists have, for some time, been advancing the idea that, if only managements and employees would sit down together and negotiate productivity agreements covering every industry, all the economic ills of Great Britain would be solved and we could all live in a state of Utopia. The fact that it is the politicians who are specially vociferous in persuading industry to negotiate such agreements fills me with deep suspicion that once again we are using wrong methods to tackle our problems. Their advocacy would be more convincing if their record of solving political problems and guiding the country's destiny had been more successful.

ULSTERBUS

There is no doubt that when productivity agreements are concluded for the first time they can have excellent results, and Ulsterbus is no exception. Our first productivity agreement was signed in February 1967. It took about four months to negotiate. Since then we have revised it and we are now at the stage where the negotiators have concluded with the company an agreement covering three years until early 1972. Without the original agreement it would have been much more difficult to form Ulsterbus out of the former Ulster Transport Authority and to enable the company to make the progress it had to make in order to reach a sound financial position.

The circumstances facing us were quite unusual. In 1966 the buses operated by the Ulster Transport Authority were running with a deficit of approximately £140,000 and depreciation was rather inadequate. The original union agreement enabled us to do something dramatic on the day Ulsterbus was formed—April 17, 1967. The day before, 1,600 duties were required to operate the services. Next day the same services, with only very minor adjustments in frequency and timing, required only 1,200 duties. Overnight there was, therefore, an improvement in manpower utilization of 25 per cent. The financial benefits were considerably greater.

After one year Ulsterbus achieved a profit of £278,000 with a grass surplus of £610,000. After our second year profits increased to £400,000 and the gross surplus to £740,000. This was achieved without a fare increase. Fares were kept unchanged from September 1963 to June this year. Not only has Ulsterbus been put in a sound financial position, but it has also managed to absorb over £400,000 in two years of additional operating costs. We also have on deposit with Belfast Corporation £800,000 in cash to pay for next year's 'buses. These results have now encouraged us to commit £2-1million to buying 300 new buses and rebuilding our dilapidated bus stations and depots.

In practical terms. we have now reached the position where all our 650 single-deck buses are one-man operated, where drivers will clean buses, where we can employ women as conductresses and cleaners, part time as well as full time, doubledeckers can be operated one-man and staff will be obliged to carry passengers up to the maximum number authorized by the p.s.v. authorities.

It must not be assumed that all this was achieved because we reached a productivity agreement. The agreement laid the foundations and created the conditions for our achievement. However, the final result was due to a lot of hard work by a considerable number of people.

Benefits to the employees

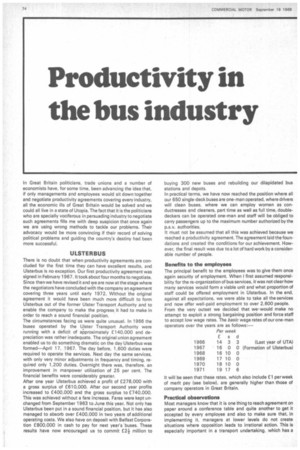

The principal benefit to the employees was to give them once again security of employment. When I first assumed responsibility for the re-organization of bus services, it was not clear how many services would form a viable unit and what proportion of staff could be offered employment in Ulsterbus. In the end, against all expectations. we were able to take all the services and now offer well-paid employment to over 2,600 people. From the very outset we decided that we•would make no attempt to exploit a strong bargaining position and force staff to accept low wage rates. The basic wage rates of our one-man operators over the years are as follows: It will be seen that these rates, which also include £1 per week of merit pay (see below), are generally higher than those of company operators in Great Britain.

Practical observations

Most managers know that it is one thing to reach agreement on paper around a conference table and quite another to get it accepted by every employee and also to make sure that, in implementing it. managers at lower levels do not create situations where opposition leads to irrational action. This is especially important in a transport undertaking, which has a dispersed labour force and where problems of communication are considerable.

In order to assist the company in overcoming difficulties which were found to arise because of the many changes which a large-scale re-organization makes inevitable, I decided right from the start on a special provision which is not generally found in trade union agreements. In the case of one-man operators, £1 per week is set aside and paid out twice a year, at the beginning of June and at the beginning of December. This money is called merit pay. Any employee who takes part in unofficial action against the company (overtime ban, work to rule, refusal to take out a bus) loses this money for the six-month period. This means that a one-man operator who goes on unofficial strike, apart from losing his wages while he is on strike, loses another £26 on top of it.

In 2-;years, merit pay was lost on three occasions. The first was the day Ulsterbus started, when one depot refused to work the duties. This lasted two days. The second was before Christmas 1 967 when two depots went on unofficial strike. The last one was a year ago when members of one of the two unions negotiating for platform staff refused to work new duties. For the past year there has been no unofficial action against the company. The merit pay has not only helped the company, it has also made life easier for trade union officials. This penal provision is highly unpopular with a proportion of the employees and several attempts were made to get it removed from the agreement. However, it is still there.

The agreement also contains the following statement:—

"The payment of these wages by Ulsterbus Limited shall be conditional upon the removal of all restrictive practices." This clause has never been invoked, There are still restrictive practices. However, these are not of any vital significance. This clause would only be used if a serious clash arose between the company and the employees.

Future of productivity agreements

In view of the undoubted benefits which our trade union agreements have given to the employees, to the company and to some extent to the travelling public, it will be difficult for me to explain why I think they will prove to be a serious embarrassment and even a possible danger to the economy in a few years' time.

At present far too many productivity agreements are nothing more nor less than means of buying out restrictive practices or opposition to change. Capital-intensive industries have, had little choice in using these means of ensuring the growth and continued financial stability of their organizations. The earnings negotiated for oil tanker drivers are a case in point. No doubt the companies concerned have reaped the benefits. However, how is another company to behave (take any large bus or transport undertaking where labour costs already form a very large proportion of the total) if it is confronted by union negotiators with such agreements? A bus driver's job is every bit as responsible as that of a tanker driver and yet our system of negotiations forces him to accept a lower wage rate.

The present Prices and Incomes legislation means that in industries which are already efficient, large increases, which can certainly be justified by union negotiators, have to be denied merely because the industries have in the past made themselves efficient and there is limited scope for productivity wage increases. Ulsterbus is already reaching a stage where the benefits from the latest agreement may possibly accrue in two or three years, but where it will be difficult to get the agreement approved by the Department for Employment and Productivity because a wage increase of £200,000 per annum can only be recovered by improvements in efficiency to the extent of £40,000 per annum.

If productivity agreements are to become a useful tool, management and unions must stop horse trading with each other and put in its place a much more responsible approach. Before this can happen, everybody ought to be clear in their minds about the real object behind productivity negotiations. In most industries management is not trying to make individual workers work harder, The real motive is to make the effort at present made by an employee more effective. This is a point which employees and their negotiators overlook or even refuse to accept. There will also have to be a more realistic approach to redundancy. In post-war years the port of Hamburg was cut off from its hinterland. It struggled along for quite a few years, but, when Rotterdam and other ports succeeded in attracting tonnage on a large scale, the blow had to come and the labour force was reduced. The last thing that either unions or employers attempted was to fight the inevitable. I wish it were possible to conduct our industrial relations in this country on a similar basis.

So far there have been relatively few productivity agreements, but let us consider what the situation would be if every firm had one. In the bus industry alone there might well be over 50 different agreements all trying to achieve the same thing. Inevitably, the good features from the trade union point of view in one agreement would be taken as an example of what should be secured in another. The best agreement from the unions' point of view would be that negotiated by the weakest and least determined management and, for some time to come, this would determine trade union claims.

There are a number of other difficulties which arise when agreements are negotiated at the level of smalland medium-sized companies. In most companies negotiations are conducted by full-time officials and shop stewards. It is very rare to find that shop stewards possess the necessary experience or ability to understand the financial implications of productivity negotiations. This means that when negotiations reach a difficult stage these shop stewards flounder through lack of experience. This prolongs negotiations and causes unrest among the employees who fail to understand the real reasons why it takes so long to reach a settlement. If the unions were able to appoint experienced negotiators much delay would be avoided and productivity negotiations would really be successful for everybody. However, we are very far from this situation.

Even when agreement has been reached around the conference table, the union officials are then faced with the problem of getting it accepted. Our latest negotiations are a case in point. After months of negotiations, agreement was reached with the negotiators. The settlement was a very good one to employees and one trade union ratified it, the vote of half-a-dozen men caused it to be rejected by the other. It is perhaps not surprising that this country is not making the progress it should if we conduct industrial relations in such a haphazard and unreliable manner,