Purple head

Page 24

Page 25

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

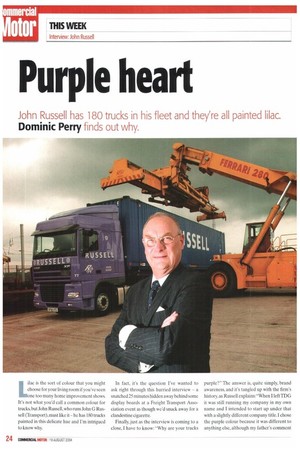

John Russell has 180 trucks in his fleet and they're all painted lilac.

Dominic Perry finds out why.

Lilac is the sort of colour that you might choose for your living room if you've seen ne too many home improvement shows. It's not what you'd call a common colour for trucks, but John Russell, who runs John 0 Russell (Transport), must like it —he has 180 trucks painted in this delicate hue and I'm intrigued to know why In fact, it's the question I've wanted to ask right through this hurried interview — a snatched 25 minutes hidden away behind some display boards at a Freight Transport Association event as though we'd snuck away for a clandestine cigarette.

Finally, just as the interview is coming to a close, I have to know: "Why are your trucks purple?" The answer is, quite simply, brand awareness, and it's tangled up with the firm's history, as Russell explains:"When I left TDG it was still running my company in my own name and I intended to start up under that with a slightly different company title. I chose the purple colour because it was different to anything else, although my father's comment when he saw the first vehicle wasn't printable."

To put all this into context you need to delve deeper into Russell's history. He began his career in haulage back in 1958 when his 21st birthday present was a pair of trucks. He ran them part time. while helping his father run his firm.

Eventually, the then fledgling TDG bought both his and his father's companies and packed him off down south to work font.

After a four-year stint as an industrial relations troubleshooter, hopping from firm to firm within TDG, Russell was despatched back up to Scotland. Prior to its consolidation, TDG owned some 16 companies north of the border; when it began revamping them as regional holding companies Russell was put in charge of the Scottish set-up.

But in the late-1960s,he recalls: It rather annoyed me three months after signing a five-year contract and I effectively gave it a four-year notice period."

This was negotiated down to a more sensible time-frame and Russell struck out on his own... it was lilac truck time.

He admits he was worried about the enterprise to start with: worried about making that leap from comfortable corporate entity to seatof-the-pants haulier. Seeing the trend towards containerisation he jumped on that particular bandwagon and containers have remained a mainstay of the business.

Inevitably, out of container haulage came a dalliance with rail freight. "I'd always been interested in rail transport, although I developed it far earlier than I should have done and it cost us a fair bit of money," he says.

Russell was the Scottish partner in the illfated Charter Rail piggyback system: "I felt quite secure with that because British Rail was a part shareholder. But nonethelessit went into liquidation and we lost £360,000. It was a fair mouthful at the time —it wasn't a debt we could afford.Thankfully, I'd been with the same bank for virtually my whole working life so there was an element of trust and assistance from it which helped us out."

Northern focus

You might think an intermodal service, 180 trucks and extensive warehousing would be more than enough to keep one person busy, but Russell also owns bulk liquid haulier Carntyne Transport. This was originally a family firm, mainly running tippers on road contracts; when Russell bought it he changed its direction to specialise in transport for the distilling industry.

Despite the size of the company, Russell has no desire to shift its focus south of Carlisle:"We are very much focused on Scotland because we know the market. We have extensive rail facilities,but we have no desire to develop these south of the border.That's not in any nationalistic sense, we'd just rather co-operate with others than develop our own activities there." Although clearly interested in rail transport Russell doesn't hold back when discussing its occasionally shambolic standards: -Rail has got to further improve its performance. It's not reliable enough yet.A lot of the goods we move on rail are FMCGs [Fast Moving Consumer Goodstand I think truck operators understand that if we're due to deliver at a set time then it's got to be there. I'm not sure that the rail industry fully recognises that yet.

Many commentators point to deep-seated cultural problems within the railway industry, and Russell's arguments follow a similar wouldn't say it always gives passengers priority, but put it this way, if everything's running on schedule then it's all very efficient. However, if there's a hiccup it is not conscious of the repercussions it can have for other users.

"If we have a problem in road transport we pull out all the stops to remedy the situation. Network Rail has a problem achieving that."

There's an argument that says rail, particularly for somewhere as geographically remote as Scotland, is the answer to innumerable freight transport problems.That doesn't convince Russell:" Rail within Scotland is much more difficult. To be successful you need a freight corridor with balanced flows and in Scotland it's very hard to do that. Even goods for the north of Scotland are brought up by rail then transferred onto road from the central belt.

"Rail is a point-to-point service," he concludes."It doesn't have that flexibility that road transport does. Even if we bring goods up by rail, we still have to get them to their final destination by road.0