HISTORY AT WORK

Page 44

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

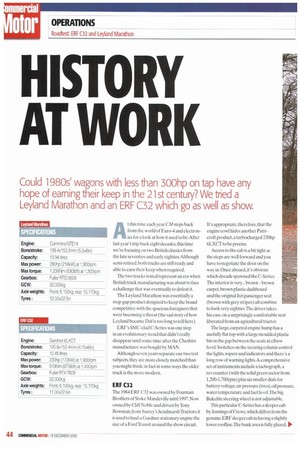

Could 1980s' wagons with less than 300hp on tap have any hope of earning their keep in the 21st century? We tried a Leyland Marathon and an ERF C32 which go as well as show.

At this time each year CM steps back from the world of Euro-4 and electronics for a look at how it used to be. After last year's trip back eight decades, this time we're focusing on two British classics from the late seventies and early eighties.Although semi-retired,both trucks are still ready and able to earn their keep when required.

The two trucks tested represent an era when British truck manufacturing was about to face a challenge that was eventually to defeat it.

The Leyland Marathon was essentially a stop-gap product designed to keep the brand competitive with the spacious foreigners that were becoming a threat (the sad story of how Leyland became Dal is too long to tell here).

ERF's SMC-clad C-Series was one step in an evolutionary trend that didn't really disappear until some time after the Cheshire manufacturer was bought by MAN.

Although seven years separate our two test subjects, they are more closely matched than you might think: in fact in some ways the older truck is the more modern.

ERF C32

The 1984 ERF C32 was owned by Fountain Brothers of Stoke Mandeville until 1997. Now owned by Cliff Noble and driven by Tony Bowman, from Surrey's SendmarshThactors, it is used to haul a Gardner stationary engine the size of a FordTransit around the show circuit. It's appropriate, therefore, that the engine cowl hides another Patri croft product,a turbocharged 230hp 6LXCT to be precise.

Access to the cab is a bit tight as the steps are well forward and you have to negotiate the door on the way in. Once aboard, it's obvious which decade spawned the C-Series.

The interior is very... brown — brown carpet, brown plastic dashboard and the original lsri passenger seat (brown with grey stripes) all combine to look very eighties.The driver takes his ease on a surprisingly comfortable seat liberated from an agricultural tractor.

The large,carpeted engine hump has a usefully flat top with a large moulded plastic bin in the gap between the seats at elbow level. Switches on the steering column control the lights, wipers and indicators and there's a long row of warning lights.A comprehensive set of instruments include a tachograph, a rev counter (with the solid green sector from 1200-1,700rpm) plus six smaller dials for battery voltage, air pressure (two), oil pressure, water temperature and fuel level.The big Bakelite steering wheel is not adjustable.

This particular C-Series has a sleeper cab by Jennings of Crewe, which differs from the genuine ERF sleeper cab in having a slightly lower roofline.The bunk area is fully glazed,

with all-round curtains.., and yes of course they're brown. There's a capacious storage box under the passenger end of the bunk and a large glovebox.

Starting involves releasing the large manual stop control and turning the key. The Gardner engine starts easily and settles into a tickover around 450rpm, at which speed it suffers considerably from the shakes. Apart from enlisting long disused muscles to help with the steering, the biggest challenge for drivers de-skilled by modern trucks is the gearchartge.

The Fuller box (four over four plus a crawler) has a widely spaced but reasonably positive gate with a sliding range-change switch on top of the lever. Selecting the first gear from a standstill involves taking the box by surprise, pushing the lever in as soon as the clutch is depressed. Smooth progress is initially hindered by the floor-hinged throttle pedal, which has a firm resistance for the first half of its travel, before going overcentre and lightening up.

It takes some getting used to.but eventually you manage to work round it.The actual changing was fairly easy to learn; the biggest handicap was being too cautious. The quicker the lever was moved, with a fast declutch in neutral, the easier it was.

Performance comparisons between the two trucks would be invalid as the ERF's Tasker low-loader was loaded to within about five tonnes of its 32 tonne gross while the Leyland was hauling an empty trailer. Nevertheless. the ERF's performance on the flat proved surprisingly lively, although the overdrive top ratio was fairly ineffectual on anything resembling a slope. On the really tough short, sharp, slope on the infamous Snake at the Chobham proving ground we well and truly screwed up the first attempt —leaving the last downshift too late, we simply ground tea halt.

Fortunately, the crawler allowed a painless restart and on the next attempt, when we changed down a bit sooner, the Gardner dug in and took the climb in its stride.

Back on the flat, reaching a top speed somewhat in excess of the current motorway limit was achieved with relative ease.Thankfully the brakes are strong and progressive and, having recently been fully overhauled, the steering was impressively tight and accurate: well up to modem, new truck standards—just heavier.

Leyland Marathon

Also a regular on the historic vehicle scene, the Leyland Marathon is used through the year to carry owner John Coakes' collection of restored commercials to shows and rallies, often meeting the Sendmarsh team at various events.The Mark One Marathon was used from new on general haulage by JBC Coakes Transport. However, John Coakes now has reduced the size of his operational fleet to just a single Volvo four-wheeler and concentrates on his collection of historic wagons. leaving the Marathon mostly to work weekends.

The Marathon started life with a naturally aspirated Cummins 250 under the lid, but it was later treated to a 290 from a scrapped Marathon, the extra 40 horses coming from a turbocharger.

The Marathon has essentially the same Motor Panels cab that is found on lesser Leyland products;it's just mounted higher.Thanks to the steps located on the rear end of the front bumper, climbing aboard needs even more care than the ERF. It's obvious that the cab was designed by engineers and not stylists — everything is functional.

The dash comprises a number of individual GRP mouldings attached to a base unit with large,conspicuous machine screws. Instrumentation is similar to the ERF in content, although the rev counter was not working which made it rather difficult to judge gear change points. it has an uncharacteristically small and thin-rimmed steering wheel which was apparently disliked by contemporary drivers for being over-responsive.

There were various sleeper cab options on the Marathon; this example boasts the longest cab which was designed for Continental work. It has glazed rear windows but solid side panels.There's something like a foot more interior length which, together with the lower engine hump, makes a big difference to the claustrophobia levels in the cab.

The sleeping area has brackets to fit a second bunk, although anyone sleeping downstairs might feel a bit hemmed in.The seats are the originals, which have been recovered in the original type of material, and are extremely comfortable.

Once on the move the Leyland has a much smoother throttle action than the ERE but this was more than negated by the much looser gear change and steering.We got off to a shaky start after being told that the Marathon's Fuller gear change was the same as the ERF's.After a few false starts, when we found a huge hole between second and third, we finally discovered that third on the Marathon was towards the driver and back, then forward for fourth, unlike the more conventional layout on the ERF. With this sorted we were able to proceed successfully.

Although the Marathon and its unladen York step-frame tandem trailer only weighed in at around 12 tonnes, the performance from the blown Cummins was obviously a class above the Gardner-powered ERE We'd go so far as to say that very few modern artics feel as lively, despite their higher outputs. And it would not be correct to mention that the unlimited Marathon can keep on going.

One genuinely authentic feature of the Marathon was the selection of draughts through the floor and door aperture, which on a longer journey would give that true period feel of one hot leg and one cold one... those were the days!