BIGGER, BETTER and Cheaper to Run

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

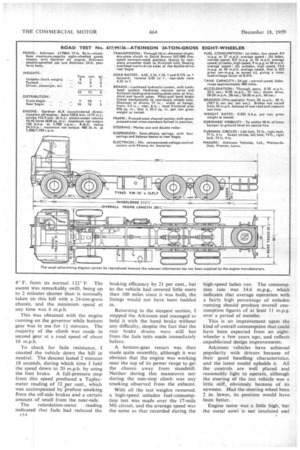

/1' is 10 years since an Atkinson eight-wheeler was tested by The Commercial Motor, and during this time worthwhile, although in most respects minor, alterations have been made to the basic design, as might be expected. A further change has been that the legal gross weight rating has been increased from 22 to 24 tons, whilst a greater range of high-powered engines is now available than in 1949.

Atkinson have for long pinned their faith to Gardner engines, and with the introduction last year of the 6LX 150 b.h.p. unit the amount of power they could offer in standard chassis was immediately increased by 20 per cent.

Good use has been made of this, and a new eight-wheeled 'chassis I tested showed a commendable allround improvement in performance although carrying some 2 tons more than the 1949 model. The most noteworthy advantage shown by the new vehicle was its fuel economy, at high speeds, a run of 17 miles over the Preston by-pass (M6) at full throttle producing a consumption rate of 9 m.p.g. at an average speed of 38 m.p.h.

These figures give a time-loadmileage factor .r.,f 8,474, which is one of the highest ever recorded in this country with a vehicle on test, and underlines the success of the latest Gardner design. .

The 1949 formula of David Brown gearbox and Kirkstall front and rear c12 axles is retained by Atkinson, with the addition of the availability of Z.F. gearboxes with some of the engines offered in eight-wheeled chassis. That the basic vehicle has not been changed unduly for 10 years reflects the success of the original design rather than an absence of progress. The Atkinson eight-wheeler has always had a reputation for being in the forefront of its class, and my test showed this still to hold.

There has been a recent change in appearance although, fortunately, the bold Atkinson radiator grille has not disappeared under the demands of modern styling. The cab shape haS been cleaned up, however, and now offers better driving visibility because of its deep, full-width curved wind screen and greater space for driver and passenger. The use of plastics panels on a timber frame has been found to simplify construction, reduce weight and ease repair problems.

The standard Atkinson eightwheeler is a rarity among British vehicles of this type in having a vacuum-hydraulic, braking system on its home-market versions. This system is not, however, of the 1949 variety, which incorporated , an uprightvacuum servo. On the current chassis, a Lockheed tandem Hydrovac servo is fitted. This gives powerful braking with a negligible amount of time-lag.

It has an advantage over the majority of air-pressure systems in that a reassuring degree of pedal sensitivity is retained—particularly important when running unladen.

Unfortunately, I was not able to test the effectiveness of this system to the full, partly because of continuous rain during the two days which I devoted to testing and partly because I had doubts about the security of the one 1-ton iron and six 21-ton concrete weights which formed the test load and only just fitted on the platform body.

A cautious stop on a wet road from 20 m.p.h. resulted in a stopping distance of 40 ft., however, which is only 2 ft. longer than was obtained in 1949 on a dry road at a gross weight of just over 221 tons. Thus, it is reasonably safe to say that under identical conditions the latest braking system would prove to be a marked advance over the original version, whilst there is the added advantage of the option_ of brakes on the second axle, giving eight-wheel braking..

The 6LX-enginedchassis offered to , me for test had the David Brown 557/480 five-speed overdrive-top gearbox and 6.25-to-1 axles, which gave the chassis a maximum speed of just over 40 m.p.h. when running at the engine governed speed of 1,700 r.p.m. The gearbox used has a bottom-gear • ratio of 6.05 to I, which gives a gradient ability of approximately 1 in 6.

When the David Brown direct-top unit is employed, the maximum speed is reduced to a little over 30 m.p.h., whilst the gradient ability is increased to I in 4. It is unlikely, however, that a fully laden eight-wheeler would be called upon to attempt such a gradient. Therefore, for normal purposes, the overdrive gearbox is better as it gives a useful top speed which can, furthermore, be employed economically.

Complete with Atkinson.built timber platform body, the length of which was 24 ft., the test vehicle had a kerb weight of 8 tons 31 cwt., which is a reasonable figure for a fully equipped eight-wheeler. I had asked for a 16-ton test load to be provided, but it turned out that some of the concrete weights were heavier than had been assumed.

The result was that the imposed load was 16 tons 8 cwt. (of which about 5 tons was behind the rear-bogie centre line), and the gross weight with myself and Atkinson's Ron Joyce aboard was ton over the legal limit. This sort of thing is not unknown in normal service, so it was decided to test irrespective of the overload.

A Comprehensive series of laden fuel-consumption tests was carried out on M6, a complete circuit of this motorway totalling 17 miles, allowing for the roundabouts at each end and starting and finishing off the motorway proper. As the motorway Was being resurfaced at the time, two-way traffic was in operation over much of its length and conditions were -typical 6f

normal British main-road trunk working.

The first fuel test was made in fairly heavy slow-moving traffic, although at times it was possible to take the speed up to about 33 m.p.h. The distance was covered at an average speed of 27 m.p.h. and the test tank showed a consumption rate of 8.9 m.p.g. a laudable figure.

Under clearer traffic conditions, a second run was made at about the same maximum speed and this gave the same

consumption rate, although the average speed was raised to 32 m.p.h. Maximum speed was employed wherever possible during the third laden run on M6, and this resulted in an average speed of 38 m.p.h.

Surprisingly enough, the consumption rate was slightly improved—the figure being 9 m.p.g.--and this was obviously because the vehicle climbed all the gradients on the route in higher gear, as it was possible to take a run at them.

For the brake tests I took the eightwheeler to Euxton Lane, which is a suitable three-lane stretch of level road. For reasons stated, I did not attempt " crash " stops from 30 m.p.h. The test from 20 m.p.h. was carried out safely, and all the wheels locked in a straight line. A maximum Tapley-meter reading of 53 per cent. was obtained.

A consumption test was made from Euxton Lane over a narrow and hilly 10-mile route to the Langton by-pass. This was not an easy run for a fullsized eight-wheeler, and I was pleased that, despite numerous stops, an average speed of 23.2 m.p.h. was maintained. The consumption rate worked out at exactly 8 m.p.g. I cannot see a lower figure than this being obtained in the course of normal service when running solo, and certainly not at such a comparatively high average speed.

From the by-pass I drove the Atkinson to the Southport Road at Tarteton, where acceleration tests were carried out. Ron Joyce started off in second gear when making the standing-start tests, and was able to reach 30 m.p.h. in fourth gear, the average time of 57 seconds recorded being good for a vehicle of this weight with a conventional engine.

As is usual when making directdrive acceleration tests with Gardnerengined vehicles, good times were obtained between 10-30 m.p.h., and because of the good low-speed torque of the 6LX and its subsequently fairly flat torque curve, almost consistent acceleration rates were recorded between 10-20 m.p.h., and 20-30 mph.

A devious route was then taken from Tarleton to the bottom of Parbold Hill. This -&-mile gradient is the one normally employed on tests in the Preston area and has an average severity of I in 12, whilst the steepest section is nearly 1 in 6.

The ambient temperature during the climb was 52° F., and 6 minutes 49_ seconds of climbing caused the engine coolant temperature to rise by only

8' F. from its normal 132' F. The ascent was remarkably swift, being up to 2 minutes shorter than is normally taken on this hill with a 24-ton-gross chassis, and the minimum speed at any time was 6 m.p.h.

This was obtained with the engine running on the governor while bottom gear was in use for 11 minutes. The majority of the climb was made in second gear at a road speed of about 10 m.p.h.

To check for fade resistance,. coasted the vehicle down the hill in neutral. The descent lasted 2 minutes 18 seconds, during which time I held the speed down to 20 m.p.h. by using the foot brake. A full-pressure stop from this speed produced a Tapleymeter reading of 32 ,per cent., which was accompanied by profuse smoking from the off-side brakes and a certain amount of smell from the near-side.

The retardation-meter reading indicated that fade had reduced the braking efficiency by 21 per cent., but as the vehicle had covered little more than 100 miles since it was built, the linings would not have been bedded in.

Returning to the steepest section, I stopped the Atkinson and managed to hold it with the hand brake without any difficulty, despite the fact that the rear brake drums were still hot from the fade teSts made immediately before.

A bottom-gear restart was then made quite smoothly, although it was obvious that the engine was working near the top of its power range to get the chassis away from standstill. Neither during this manceuvre nor during the non-stop climb was any smoking observed from the exhaust.

With all the test weights removed, a high-speed unladen fuel-consumption test was made over the 17-mile M6 circuit, and the average speed was the same as that recorded during the high-speed laden run. The consumption rate was 14.6 m.p.g., which indicates that average operation with a fairly high percentage of unladen running should produce overall consumption figures of at least 11 m.p.g. over a period of months.

This is an improvement upon the kind of overall consumption that could have been expected from an eightwheeler a few years ago, and reflects unpublicized design improvements.

Atkinson vehicles have achieved popularity with drivers because of their good handling characteristics, and the latest model upholds it. All the controls are well placed and reasonably light to operate, although the steering of the test vehicle was a little stiff, obviously because of its newness. Had the steering wheel been 2 in. lower, its position would have been better.

Engine noise was a little high, but the metal cowl is not insulated and was not covered by a quilt, the addition of which would have done much to quieten the cab Interior.

A wide range of forward vision is given by the new windscreen design, but larger driving mirrors would have been an advantage, particularly when reversing in confined spaces. Cab

heating and demisting equipment was fitted to the test vehicle and I noted

that the four demister nozzles were well placed and cleared the screen effectively. Because the Gardner engine never gets really hot, however, the cab heating left something to be desired.

The cab has a particularly good finish, both inside and out, and the quality of the plastics panels is high. A change is shortly to be made in the rear framing to allow the driving seat to be adjusted farther back than it will go at present. This will be advantageous. Stowage space is restricted to a shelf above the windscreen.