What._aload

Page 53

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

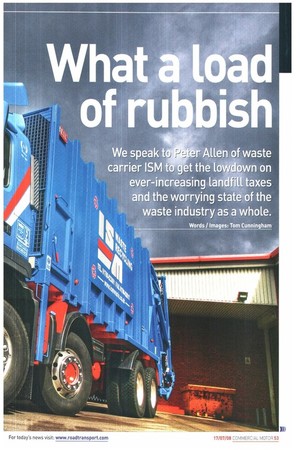

We speak t Allen of waste carrier ISM ts set the lowdown on ever-increasing landfill taxes and the worrying state of the waste industry as a whole.

Words / Images: Tom Cunningham

Introduced 12 years ago, taxation on landfill-dumped waste was meant to signal a change in direction for UK plc and the waste it generates. Even Joe Public agreed that dumping waste en masse was not the way forward. The price of waste was originally set at f7/tonne. Today, we're at 02/tonne. Next year it increases to £40/tonne, before rising further in two .E8 increments until it reaches a staggering £56/tonne. And this is all before the landfill owners themselves pass on any increases in site fees.

"We've been used to [tax] increases in the region of £3 year on year, but the Di lump was seen as an aggressive move by the entire industry," says Peter Allen, managing director of Lancashire-based waste carrier ISM. He adds that the gate price (the overall price paid to landfill) is already nearing the £60/tonne mark. if you were blinkered enough to think large waste carriers were the only voice worth listening to, it would be easy to draw the conclusion that the industry had spent the past 12 years putting two fingers up at the government's reduction targets. But that's simply not true."

The whole situation continues to become a major irritant for ISM: "For years and years, we've known landfilling waste is not a sustainable option for disposal. We've also known that the landfill tax would increase on an escalator basis. Which bit caught everyone out?" asks Allen, whose contempt for large waste operators grows stronger by the day.

Together with sales director Andy O'Neill, brother John and the rest of the hard-working family, he runs an 18-truck commercial waste disposal operation within a 30-40-mile radius of Ramsbottom. The business was established in 1964 by John Allen Sr and has been actively recycling since 1978. "We're in a situation where the Government thinks the industry only comprises of the likes of SITA, Shanks, Biffa, Cleanaway, Veolia etc. It also believes it atone will bring the step changes required, ignoring the fact that many of us have done so already."

You might think a savvy waste operator would be all in favour of dumping everything their vehicles collect into the nearest hole in the ground. After all, it's currently the most profitable thing to do. But clearly, it's not that simple.

Sorting the loads

Since October 2007, all waste has to be pre-treated — by law. The way in which each EC country interprets the word 'pre-treat' (that's recycling, to you and me) is a hot topic in itself, despite Environment Agency (EA) guidelines. Pre-treatment can be physical, thermal, biological or chemical. Here in the UK, waste operators currently have two main methods of disposal: they can either send the vehicle's contents through a materials recycling facility (MRF), where it begins a pre-treatment process, or get the waste producer to pre-treat before collection. But it's a paper exercise with next to no tangible policing.

ISM Waste favours the MRF route, which means the co-mingled load is completely tipped and then sorted into wood, cardboard, glass etc. Reusable items are sent for recycling; the remainder is collected together with other unusable waste and sent to landfill. The producer only has one skip to contend with, rather than three or four.

Waste generated via the producer pre-treatment route, however, can, surprisingly, be less sophisticated: "If you had a 20-tonne load, which contained a handful of pretreated ink cartridges, then the whole consignment is considered to he pre-treated — and only because someone's signed a piece of paper to say so. It's a bizarre set of circumstances, and is wide open to abuse," Allen reports. "In essence, we rely upon landfill, but in a much lesser way than the people who simply dump everything they collect. In the present climate, we're being penalised because they [the big operators] failed to read the future correctly — despite being told over and over again."

He may have a point. Back in May 2006, at the London launch of the Sustainable Transport of Resource and Waste report, a multinational company's director of external affairs claimed that -nobody but an idiot" would choose to build treatment facilities unless they could guarantee feedstock through long-term local authority contracts. He went on to conclude that investment in the likes of MR.Fs wouldn't he required until 2010-2011, when the predicted £50/tonne landfill tax arrived.

That particular external affairs director has, we gather, since backtracked on what he said. "With comments like that, you can hardly blame the Government for taking a strong Line against landfill," says Allen. "I never thought I'd hear myself saying it, but thank God for the landfill tax? At the end of the day, it's all about money. Lip service has been paid to environmental impact by the big firms who now control huge parts of the nation's waste collection."

So why do the big operators continue to lobby for continued landfill use when the tide is obviously turning against them? Allen is rather cynical. He says: "It's a bit of a no-brainer. If you owned a collection of landfill sites and benefited hugely from the income they generated, what message would you be broadcasting? Would you want your collection division promoting recycling practices at the detriment of your landfill division? The big players have available landfill space, thousands of trucks collecting waste, and next-to-no recycling facilities. Their entire operations are landfill-dependent. They've been well and truly caught with their pants down."

Allen fears that some small to medium-sized companies, reliant solely upon landfill for disposal, will go to the wall, whereas the larger players are likely to either build MRF infrastructures or access large-scale recycling methods thorough acquisition. "We've already seen some companies specialise in niche parts of the business, such as wood, glass and tyres, as a means of survival."

Targets and quotas

He adds: "Let me give you a theoretical example: you've got a multi-pickup round using a frontor rear-end loader. Client one has only removed cardboard to pre-treat, client two has only removed glass, client three has only removed bricks.., but then client four hasn't removed anything. He wants you to do the pre-treating. Under the current way of working, the load is now contaminated and can't go straight to landfill. [But] given all of the recent financial strains the industry has to bear, you'd have to be naive to think the load doesn't go straight off to landfill."

The answer, according to ISM, could be incentives or legislation rather than just raising taxes. "The Government argues taxation on pollution and waste generation filters down to the root cause, but in our opinion that seldom happens— and if it does, it's not the full cost," says Allen.

Taking legislation as a possible solution, the puzzling hit for the likes of Allen is Defra's Landfill Allowance Trading Scheme (LATS). Introduced to make sweeping changes in English municipal waste policy, the scheme is intended to help meet targets for the reduction of landfilldeposited biodegradable waste under Article 5(2) of the EC Landfill Directive. Under the directive, councils have specific landfill reduction targets to meet. Councils will be fined £150 (on top of the current landfill tax and gate price) for every tonne of their quota exceeded. Allen has a question: "Why wasn't it extended to commercial waste collectors?" If so. he argues, large waste collectors would be forced into large-scale recycling programmes sooner.

Follow our example "It's a bit galling when the Government thinks the waste industry is four or five multinationals and a couple of large waste producers. It's been the smalland mediumsized players who've had the foresight to bring about the sorts of changes the entire industry will now have to follow. In this area alone, we regularly see fully laden trucks absolutely haemorrhaging recyclables."

To this end, Allen says he has consistently campaigned for more regulation. "I've even thought about taking the whole lot to the European Parliament myself. Our Government has misinterpreted the EC legislation. We're solely reliant upon landfill tax as the big stick to make change. But its so open to abuse. If you generate a million tonnes of waste a year, just one skipload counts as a complete pre-treatment. It's a crazy situation and something's got to be done. Some 98% of all waste collected by ISM goes through our MRF. If we can do it, then so can the rest of the industry," he concludes. •