SURE AS THI UNSET

Page 106

Page 107

Page 108

Page 109

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By the Technical Editor

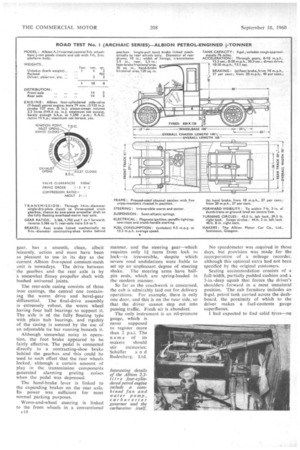

UNRIVALLED forward visibility, an easy-access cab with uncluttered floor line, a high degree of engine accessibility, a foot-operated transmission brake, and starting, lighting and ignition systems which dispense with the need for a battery—these are features of the Albion A14 4-tonner. It is a model which has not been announced recently by the Albion Motor Car Co., Ltd.. Seotstoun, Glasgow, now perhaps more familiarly known as Albion Motors, Ltd.

The A14, like many present-day -}-tonners, was originally derived from a private car, in this case the memorable Albion 15 h.p. model, the last private car to have been built by Albion's. The particular vehicle that I road tested was a 1912 design, which had been delivered to Shute Bros., of Manchester, in June, 1914, and was eventually acquired by Lord Montagu of Beaulieu.

Before heading south for rustication in Hampshire, the vintage (or is it veteran?) lorry was returned to its native land for a cheek at the old Halley works at Yoker, premises which now form part of the Albion organization. Here it was merely. made runnable and was by no means overhauled to the extent of making it equal to its original condition.

When NA 1433 was built, life was decidedly more leisured than it is today. The engine was governed to 1,250 r.p.m., to give a maximum speed of approximately 21 m.p.h., at Which pace it had the better of horse-drawn traffic. It can be assumed that the average driver of a 4-tonner in those days had graduated from horse-drawn transport and was used both to getting up early and to manual exertion—two essential qualifications when starting from cold. In 1914, the widespread use of horses and steam vehicles ensured the availability of ready supplies Of water wherever the internal combustion engined vehicle might roam. Nowadays, a journey of 12 miles which requires neatly four gallons of water is fraught with difficulties, particularly as clouds of steam tend to impede fosrward vision.

Although the pace andefficiency of modern delivery vehicles have improved during the course of 46 years, chassis layout has not altered to the same degree. Admittedly, the Albion A14 was an advanced design in its day, and the chassis frame is basically of ladder formation, swept inwards in the vicinity of the gearbox to provide turning clearance for the front wheels. .

Riveting was employed during assembly, although several bolts seem to have found their way into the frame over the years, and it is interesting to note that even in those days Albion were using tubular cross-members.

Semi-elliptic springs at front and rear, although undamped, deal admirably with adverse road surfaces. The overheadworm rear axle does not have to rely solely on springs for location, there being a hefty torque stay to provide a modicum of fore-and-aft location and to accommodate driving and hand-braking torques.

Although Albion's provided a brandnew driver's handbook, it gives little information about the power potential of the 15 12.p. petrol engine. This has a T-head layout with twin camshafts driven by spur gears from the front of the crankshaft.

The cylinder head and block are a one-piece casting, bolted to the two-piece cast-aluminium crankcase, but attention to the valves is simplified by the provision of a removable plug in the top of the head above each valve.

This provision is important if attention is paid to the handbook, which suggests that the exhaust valves should be ground slightly, using emery flour and oil, every month. Accessibility is demanded also by the recommendation. that, if " popping " occurs in the carburetter, a suction valve is probably sticking and should be removed immediately and cleaned in paraffin.

Three plain bearings support the crankshaft, and forced lubrication is provided by a gear-type oil pump submerged in the sump and driven through skew gearing from the exhaust camshaft. The trouble of removing, wiping and reinserting a dipstick is avoided by the provision of a icycl cock on the side of the crankcase to indicate the oil level. Several piston rings are provided in each cast-iron piston and, according to the handbook, these should not become "unduly worn" until after the engine has been running a number of years.

It is in respect of the auxiliary details that the Albion unit is particularly advanced for its years. For example, the 1.5 hp. engine was one of the first ever to have been built with a combined fan and water pump assembly, the design of which was the subject of an AlbionMurray patent. This unit is driven by a flat belt.

The subject of another Albion patent is the. water-jacketed carburetter, which contains many novel devices. Some of them appeared on test to work reasonably well, despite. the absence of any connection between the carburetter and

its patented governor. The governor was claimed to be tamper-proof in that it was enclosed in the crankcase, so it must have been old age that had put it out of action

Ignition is • provided—somewhat sporadically, it must be admitted—by a Lucas G.A.4 magneto, driven at crankshaft speed through a fibre coupling. This magneto has two internal earns to control the opening and closing of the contact points, but subsequent examination revealed a certain misalignment whereby one opening was about

and the other about 0.005 in.—settings not conducive to easy starting.

The engine is solidly mounted in the chassis frame, but it ran smoothly and an almost negligible amount of vibration

was transmitted to the driver. The spoked 16.k-in.-diameter flywheel on the rear of the crankshaft carried-7-some

what surprisingly single-dry-plate clutch (another Albion-Murray patent), as opposed to the leather-faced cone clutch more commonly used in those days. This clutch has a slotted disc to prevent heat distortion.

Behind the clutch there is a threespeed crash-type gearbox, the changespeed mechanism for which is remotely mounted, so that the lever lies to the right of the steering column, where it is well out of the way of driver and passenger.

The box, which includes a reverse r17

gear, has a smooth, clean, albeit leisurely, action and must have been as pleasant to use in its day as the current Albion five-speed constant-mesh unit is nowadays. The drive between the gearbox and the rear axle is by a somewhat flimsy propeller shaft with bushed universal joints.

The rear-axle casing consists of three iron castings, the central one containing the worm drive and bevel-gear differential. The final-drive assembly is extremely robust, the worm wheel having four ball bearings to support it. The axleis of the fully floating type with plain hub bearings, and rigidity of the casing is assured by the use of an adjustable tie bar running beneath it.

Although somewhat noisy in operation, the foot brake appeared to be fairly effective. The pedal is connected directly to a contracting-shoe brake behind the gearbox and this could be used to such effect that the rear wheels locked, although a certain amount of play in the transmission components generated alarming grating noises when the pedal was depressed.

The hand-brake lever is linked to the expanding brakes on the rear axle. Its power was sufficient for most normal parking purposes.

Worm-and-wheelsteering is linked to the front wheels in a conventional FIR manner, and the steering gear—which requires only 1-1turns from lock to lock—is irreversible, despite which severe road undulations were liable to set up an unpleasant degree of steering shake. The steering arms have ballpin ends, which are spring-loaded in the modern manner.

So far as the coachwork is concerned, the cab is admirably laid out for delivery operations. For example, there is only one door, and this is on the near side, so that the driver cannot step out into passing traffic. Fresh air is abundant.

The only instrument is an oil-pressure gauge, which is never supposed to register more than 2 p.s.i. The name of its makers should stir memories; Schiffer a p d Budenberg, Ltd. No speedometer was required in those days, but provision was made for the incorporation of a mileage recorder, although this optional extra had not been specified by the original customers.

Seating accommodation consists of a full-width, partially padded cushion and a 3-in.-deep squab that forces the driver's shoulders forward in a most unnatural position. The cab furniture includes an 8-gal. petrol tank carried across the dashboard, the proximity of which to the driver makes a fuel-contents gauge superfluous. I had expected to find solid tires—on the rear at least—but to my delight discovered pneumatics on each of the wooden-spoked wheels. These were of Dunlop manufacture, the size being 820 x 120.

The vehicle was delivered to Temple Press Limited on a trailer. Nevertheless, I was assured by its keepers that starting, driving and maintenance were relatively straightforward, although within two hours I began to have doubts about starting.

Subsequent exertions by myself and a large number of colleagues led me to acquire a tow rope as an essential adjunct to cold starting. With the engine hot it was sometimes possible to cajole it into action with the handle, but much depended on taking it by surprise and getting the various carburetter and ignition control levers in the correct magical sequence. Grossly retarded ignition time might have been the primary cause of trouble.

Polished Boards

It seemed unfair even to contemplate putting a test load on the dear old thing, partly because it might have damaged the beautifully polished boards of the 7-ft. 2-in. platform body, and partly because Lord Montagu's representatives had warned roe that the rear-axle gears had seen better days. Test figures were therefore taken unladen at a gross weight of I+ tons, of which 151 cwt. was being carried by the front wheels.

A fairly energetic journey out to Enfield from Clerkenwell was made without much trouble other than one aoiling session. The following morning the vehicle started easily after having been towed for less than ,+ mile, though I must confess to some half an hour's handle-turning before the towing medium appeared.

Acceleration times recorded between a standstill and 20 m.p.h. are decidedly better than would be achieved with the majority of horse-drawn +-ton vans. Indeed, they would have been exhilarating but for a. gear-change so slow that between bottom and second gears he vehicle almost came to a standstill. The direct-drive acceleration was surprisingly rapid, and obviously the engine stilt had good low-speed torque characteristics. "rop-gear performance was remarkable in all circumstances when the engine was working correctly.

A Tapley meter was used to record braking efficiencies and the 40 per cent. obtained from 20 m.p.h. with the foot brake should have satisfied any passing Ministry of Transport vehicle examiner, though the 27-per-cent, efficiency provided by the hand brake might not have been so acceptable.

There was little point in doing hillclimbing cooling tests, as the Albion was able to boil quite happily on the level. Restarts were, however, made on a 1-in-10 slope (erroneously labelled 1 in 9), and smooth, part-throttle get-aways were made in both bottom and reverse ratios. The hand brake held the vehicle safely facing uphill and downhill.

For a fuel consumption test I drove back to Clerkenwell---a distance of 13 miles from Enfield—and the journey through city traffic took only 424 minutes, giving an average speed of 18.2 m.p.h. The consumption rate was a little disappointing-9.5 m.p.g.—hut at least less petrol than water had been used.

The towing car followed meduring this test, as it had done during the other performance tests, so that I could get some indication of my speed. • On the flat I reached 25 m.p.h. at times, and 28

m.p.h. was recorded downhill. These speeds were excessive, however.

It is . indeed, unfortunate that the governor was not in operation, because a .subsequent journey caused the death of the engine. Exact details of its complaint are not known, but at least one cylinder bore was full of oil, and possibly some of the others. Consequently, I had to crawl along in second gear on level stretches and •in bottom gear on hills, and could not restart the engine once it had finally croaked to a standstill.

Abrupt Steering

Steering was good on straight roads, although a little abrupt on corners, and, apart from the discomfort of the driving seat, the• ride itself was reasonable. • Although • smooth, the engine was fairly noisy, most of the din coming from

the timing gears. Access to the power unit was particularly easy, whilst the clutch and gearbox could be reached after lifting out the floorboards, which were not bolted to the rest of the cab,

The Albion A14 -Harmer would lend a distinctive touch to any present-day fleet, but would hardly be an economic asset. In its time, it was undoubtedly a fine, mechanically advanced vehicle, and sold for a mere £347 10s. Although this is less than many 4-ton vehicles sell for these days, I would not like to recommend that it should go back into production.