STEAM VEHICLE DEVELOPMENTS.

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Lines Upon which the Future Developments of Steam Motor Vehicles May be Directed. The Possibilities of the Water-tube Boiler and of the Turbine Engine.

ALTHOUGHSTEAM-PROPELLED road vehicles were introduced over a century ago, their development is still in a very interesting stage, as evinced by the new models recently introduced by the NationaleSteare Car Co., Ltd., of Chelmsford, by Robey and Co., Ltd., of Lincoln, and described in previous issues of TheCommercial Motor'. With the exception of these concerns, very little enterprise has been shown by steam vehicle makers during the last decade, the main endeavour in the motor vehicle industry having been concentrated upon the internalcombustion-engined vehicle, which has resulted in the evolution of that type to a very high degree of mechanical perfection.

The present-position with regard to feieI supplies, however, has once more focussed interest upon a type of motor which can be operated on a cheap and pleaWill fuel such as coke. This fuel is undoubtedly most suitable for steam motor vehicles, and there is every likelihood of an abundant and increasing supply.

At the present time the majorityof steam vehiciles are rim on Welsh coal; in fact, with the predominant type of boiler in use, i.e., the bocci type, Welsh coal is a" sine qua non." It is very interesting to note, however, that all the early types were operated on coke fuel ; by 'early types is here meant thosesuch as Trevethick's 1804, Gurney's 1825, and Hancoek'a 1831. Each had its distinctive type of boiler, and exceptional originality in design was shown_ But private interests. pr evented' their development, and eventually they were prohibited from use on the highways by Act of Parliament.

For the subsequent period the development of selfpropelled vehieks was restricted to railways, and the introduction of Stephenson's loComotiVea fixed the type of boiler which has.held the'field on railways to the present day. Even here, however, coke was still the original fuel, but the demand or higher power led to the introduction of coal as 'fuel, on account of its higher rate of combustion per square fcot. of grate area and, particularly, because it contained a higher percentage of volatile matter which produced the hot gases necessary to utilize the:. heating surface contained in the tubes. This surface amounts roughly to 9Q per cent, of the total surface in this type of boiler. In 1861 Messrs. Aveling and Porter ,*Ltd., of Rochester, exhibited the first practical traction engine,aand it is not surprising that the loco type of boiler should have been adopted. as the one most suitable. The traction engine of to-day has been but little altered from that of. 1.861.

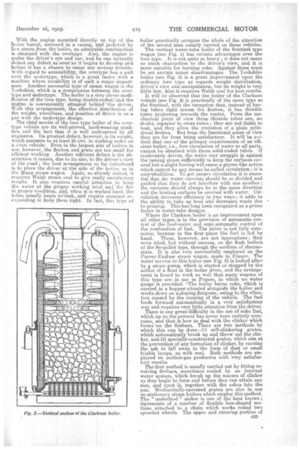

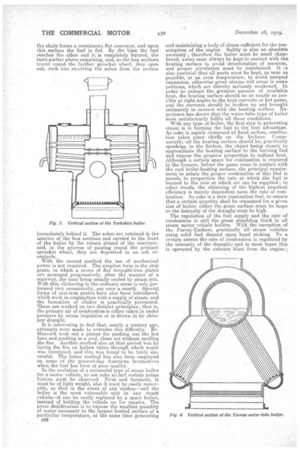

The "Red Flag" Act of 1865 checked progress, whilst the Act of 1896 provided too low a weight limit. The Heavy Motor Car Order of 1904 improved matters, for then the weight limit was 'raised to five tons unladen for the motor, and 64 tons unladen for the motor and trailer. The speed limit was.., also revised and made dependent upon axle weightiand type of Lyres, varying from 5 to 12 miles per hour. Most of the steam vehicles then introduced were of what is termed the undertype, i.e., the engine underneath the platform, and had a vertical boiler of either the water tube or fire tube type. However the introduction of the roden wagon, in the War (Ace Trials in 1901, created 'a fashion in steam motor vehicles which, with one or two exceptions, holds the field at the present time. This type is, to all intents and rarposes, a small traction engine fixed between the shafts of a two-wheeled cart. Its popularity was undoubtedly won because of its similarity to the traction engine, which had become very' familiar to haulege contractors, and because it could be easily mankpnlated by any man with previous experience in driving a traction engine. Strictly speaking, jhe overtype steam wagon was never designed for the particular work to -which it has been put ; it is really a combined traction engine and trailer wagon. It possesses its progenitor's quality of heaviness—an essential quality in the traction engine, where the hauling power depends so largely on the adhesion of the driving wheels, but one which is entirely' unnecessary in the motor wagon with which the loadperforms this duty. No .doubt this solid construction has been an important factor in achievinglihe present popularity, by its effect upon thefmaintenance charges and its reliability of performance. Now, however, the competition of the internal-combustion vehicles renders it .necessary to attack the problem from its own particular point of view, which, pint concisely, is that the vehicle shall carry the highest possible percentage of the total weight as paying load. . There is one notable exception to the prevailing overtype design, and that is the Sentinel undertype steam wagon. This is practically the only undertype design which has survived out of about 20 Britishbuilt steam wagons of this type introduced since 1896. Certain advantages over the overtype are claimed for this -vehicle ; e.g., more effective distribution of weight, shorter . wheelbase, and better position for driver. . These, however, are not points of a radical nature, for, with certain modifications, the overtype can be made to conform to these requirements. With the engine mounted directly on top Of the boiler barrel, enclosed in a casing, and jacketed by live steam. from the boiler, an admirable combination is obtained with the overtype. Also, the engine is under the driver's eye and ear, and he can instantly detect any defect as sooaas it begins to develop and before it has a -chalice to cause any serious trouble. With regard to accessibility, the overtype has a pull over the undertype, which is a great factor with a machine where reliability is of such a major importance. Another successful type of steam wagon is the Yorkshire, which is a compromise between the overtype and u_ndertype. The boiler is a very clever modification of the loco type, being double-ended,rand the engine is conveniently situated behind-lhe driver, With this arrangement, the effective 'distribution of the weight, wheelbase, and position of driver is on a par with the undertype design. • The chief merits of the loco type boiler of the overtype vehicle are its well-proved, hard-wearing qualities and the fact that it is well understood by all engineees. Its greatest defect, however, is its weight, which amounts to at least 25 cwt. in working order on a 3-tan vehicle: Even in the largest size of boilers in use, however, the firebox and grate are too small for efficient working. Another inherent defect is the obstruction it causes, due to its size, to the driver's view of the road; the best arrangement so far introduced is to place the driver at.the side of the boiler, as in the Mann steam wagon. Again, as already stated, it requires Welsh steam coal to give really satiafactory results. It also requires careful 'attention to keep the water at the proper working level and the fire in proper condition, and, when it is worked hard, the tubes usually begin tolleak, and require constant reexpanding to keep them tight. In fact, this type of

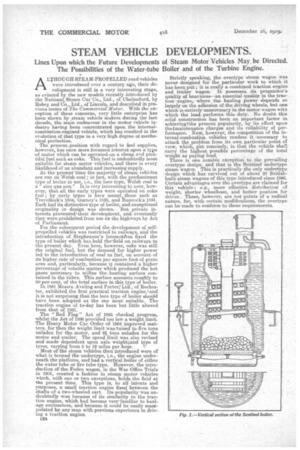

boiler practically °envies the whole of the attention of the second man usually tarried on these vehicles. The vertical water-tube boiler of the Sentinel type wagon (see Fig. 1) has certain advantages over the loco type. It is not quite so heavy ; it does not cause so mueli obstruction to the driver's view, and. it is more suitable for burning coke. Against :these must be set certain minor disadvantages. The Yorkshire boiler (see Fig. 3) is a great improvement upon the ordinary loco type as regards weight distribution, driver's view and manipulation, but its weight is very little less. Also it requires Welsh coal for best results. It will be observed that the boiler of the Clarkson vehicle (see Fig. 2) is practically of the same type as the Sentinel, with the exception that, instead of having tubes right across the firebox, it has thimble tubes Projecting towards the centre. From the mechanical point of view these thimble tubes are, no doubt, auperier to cross tubes ; they are not liable to leak, and they allow the retention of a plain cylindrical firebox. But from the functional point of view they are far from being. satisfactory. It will be evident that one of the primary requirements of an efficient boiler, i.e. free circulation of water to all parts, cannot be obtained with these solid-ended tubes. if moderately driven, the water may struggle in against the issuing steam sufficiently to keep the surfaces covered but a slight forcing will cause a, geyser-like action which cannot by any means be called circulation ; it is onlyiebullition. To get proper circulation it is essential that the water eurrents should be so divided and guided that they do not interfere with one another ; the currents should always be in the same direction and the heating surfaces be covered with water. Circulation increases efficiency in two ways ; it adds to the ability to take up heat and decreases waste due to priming. This has long been recognized as a prime factor in water-tube designs. Where the Clarkson boiler is an improvement upon all other types is in the provision of automatic control of the feed-water and semi-automatic control of the combustion of fuel. The latter is not fully automatic, because in the first •place the fuel is fed by hand. These, however, are not innovations ; they were tried, but without success, on the fla,sh boilers of the Serpollet type, through the medium of thermostats. It is also very successfully employed on the Purrey-Exsha,w steam wagon, made in France. The water serviCe to this boiler (see Fig. 5) is looked after by 2, steam pump, which is started or stopped by the i action of a float n the boiler drum, and the arrangement is found to work so well that many wagons of this type are in use in France, in which no water gauge is provided. The boiler burns coke, which is carried in a hopper situated alongside the boiler and works down on &sloping fireg-rate, owing to the vibration eauAed by the running of the vehicle. The fuel feeds forward automatically in a very satisfactory way and requires very little attention from he driver. There is one great difficulty in the use of coke fuel, which up to the ,present has never been entirely overcome, and that is how to deal with the clinker which forms on the firebars. There are two methods by which this can be donee-(1) self -elinkering grates, which automatically break up and throw out the clinker, and (2) specially-constructed grates which aim. at the prevention of any formation of clinker, by causing the ash to fall away in the form of dust or small friable lumps, as with coal. Both methods are employed on suction-gas producers with very satisfactary results. The first method is usually carried out by fitting revolving firebars, sometimes cooled by an internal water system, which break up the masses of clinker as they begin to form and before they can attain any size, and eject it, together with the ashes into the pan. Mechanically-operated grates are also in use en stationary steam boilers which employ this Method. The " underfeed " stoker is one of the best known ; iticonsists of a number of flexible box-shaped sections attached to a chain which works round two sprocket wheels. The upper and entering portion of the chain forms a. continuous 'flat conveyor, and upon this surface the fuel is fed. By the time the fuel reaches the other end it is completely burned, the inert matter above remaining, and, as the box sections travel round the farther sprocket wheel, they open out, each one receiving the ashes from the section immediately behind it. The ashes are retained in the interior of the box sections, and carried to the front of the boiler by the return strand of the conveyor, and, in the process of passing round the primary sprocket wheel, they are deposited in an ash receptacle.

With the second Inethod the use of mechanical power is not required. The simplest form is the step grate, in which a series of flat wrqught-iron plates are arranged progressively, after the manner of a stairway, the bars Being usually cooled by steam jets. With this, clinkering in the ordinary sense is only performed very occasionally, say once a month. Special forms of cast-iron grates have also been introduced, which work in conjunction with a supply of steam, and the formation of clinker is practically prevented. These are worked on two distinct principles; that is, the primary air of combustion-is either taken in under pressure by steam impulsion or is drawn in by chimney draught. It is interesting to find that, nearly a century ago, attempts were made to overome this difficulty. Mr. Hancock took out a patent for pushing out the hot bars and pushing in a cool, clean set without spoiling the fire. _Another method also at that period was by laying the fire on hollow tubes through which water was circulated, and this was found to be fairly successful. The latter method has also been employed on some of the present-day American locomotives when the fuel has been of poor quality. In the evolution of a successful type of steam boiler for a motor vehiele, to use coke as fuel certain prime factors must be observed. First and foremost, it must be of light weight, also it must be easily removable, so that in the event of any 'mishap—and the boiler is the most vulnerable unit in any steaffi vehicle—it can be easily replaced by a spare boiler, instead of holding the vehicle up for repairs. The i

great desideratum s to expose the smallest quantity of water necessary to the largest heated surface at a particular temperature, at the same time generating e26

and maintaining a body of steam sufficient for the consumption. of the engine. Safety is also an absolute necessity • therefore the boiler must be small chambered, water must always be kept in contact with the heating surface to avoid deterioration of material, and proper circulation must be maintained. It is also essential that all parts must be kept, as near as possible, at an even temperature, to avoid unequal expansion, otherwise great strains will occur in some portions, which are thereby seriously weakened. In order to extract the greatest amount of available beat, the heating surface should be as nearly as possible at right angles to the heat currents or hot gases, and the currents should be broken up and brou ht intimately in contact with the heating surface.Experience has shown that the water-tube type of boiler most satisfactorily fulfils all these conditions. With any type of boiler, the first step in generating steam is in burning the 'fuel to the best advantage. As coke is mainly composed of fixed carbon, combustion takes place chiefly on the fire-bars. Consequently,'all the heating surface should be, practically speaking, in the firebox, the object being closely to approximate the heating surface to the burning fuel and expose the greatest proportion to radiant heat. Although a certain space for combustion is required in the furnace, before the gases conic in contact with the cool boiler-heating surface, the principal requiremeat to attain the proper combustion of this fuel is merely to proportion the rate at which the fuel is burned, to the rate at which air can be supplied ; irs other words, the obtaining of the highest practical efficiency is merely dependent upon the rate' of combustion. As coke is a slow combustion fuel, to ensure that a certain quantity shall be consumed for a given size of 'boiler, either the grate surface must be large or the intensity of the draught must be high.

The regulation of the fuel supply and the rate of combustion is still the great stumbling block' in all steam motor vehicle boilers. With the 'exception of the Purrey-Exshaw, practically all• steam vehicles using solid fuel depend upon hand stoking. To a certain extent the rate otcombustion is regulated by the intensity of the draught; and in most types this is operated by the exhaust blast from the engine,; Le., the greater the power developed the stronger the exhaust blast, which thereby increases the rate of s combustion, providing the fuel is correctly supplied. With the Clarkson chassis the exhaust from the engine is condensed and returned to the boiler--which .a great advantage, as 'it increases the radius of action of the vehicle—therefore the draught is operated by jets of live steam automatically controlled by the steam pressure. To obtain .full automatic regulation of the combustion, as well as the

• draught being regulated it is necessary that the sup,: ply of fuel should be continuous and at a rate depending upon the demand for steam. With the loco type boiler the supply depends upon the skill of the stoker, who varies the feeding according to the state of the fire, which is under his observation when running. With the vertical type of boiler, such as the Sentinel and Clarkson, where the fuel is fed in at the top, the stoking is much more haphazard, as it is not possible for the stoker to see the condition of the fire.

A possible solution of the -difficulty would be the application of a m e ehanicallyoperated firegrate, regulated 'according to the amount of steam supplied to the ongine. It would not be correct to operate it from some moving part of the vehicle, for, obviously, when the vehicle is travelling downhill no steam supply is • necessary and therefore no fuel should then be supplied. That is one weak point in the Purrey Exsha w boiler, where the fuel supply is governed by the vibration caused by running. Again, the state of the roads would have a great effect, out of all proportion to the power required for propulsion. It would be' an easy matter to construct the firegrate so that, as well as automatically feeding the fuel, it clears itself of clinker at the same time, thus fulfilling the essential .consiitions for successfully burning e-oke.

A new system of ,burning solid fuel is being introduced on railway locomotives, which offers great possibilities, namely, the use Of Pulverized fuel. Although it has been found impossible to burn plain anthracite coal—which is practically equivalent to coke—owing to the low contents of volatile matter, mixtures of 60 per cent. waste anthracite and 40 per cent. bituminous screenings, pulverized together, gave excellent results. The prepared fuel gravitates from an enclosed bunker to a conveyor screw, which carries it to a fuel and _pressure air feeder, Where it is thoroughly commingled with the air and 'carried to the fuel and pressure air nozzles, and blown into the fuel and air mixers. Additional induced air is supplied in the fuel and air mixers, and this mixture, then in a combustible state, is blown into the furnace. Experiments with this system have shown a 15 per cent. saving in fuel consumption as compared with the hand firing, with a boiler efficiency of 77 per cent., in addition to a more perfect steaming boiler.

A superheater is also a very necessary adjunct, for

1111111111111111

it is most essential that dry steam should be supplied to the engine, Here, again, certain principles must be applied to obtain maximum efficiency. It should be situated above the water level oft-he boiler to avoid possibility of its being flooded with water. The steam should be split up into as many small streanas as possible, by using small diameter tubes for the coils. The coils should also be arranged in a twisted or zigzag fashion, so that the 'steam is thoroughly mixed and brought into contact with the walls of the tubes, and so will take 'up the maximum amount of heat. It should also pass through the superheater at a high velocity, for two seasons ; first, because the faster a substance passes over a hot surface the quicker it will extract the heat ; and, secondly, because prevents overheating of the coils. Another important factor is that the steam should flow through the superheater in the opposite direction to the flow of the hot gases, so that the saturated steam enters

at the coolest part of the superheater and the • superheated steam leaves at the hottest part. A very suitable

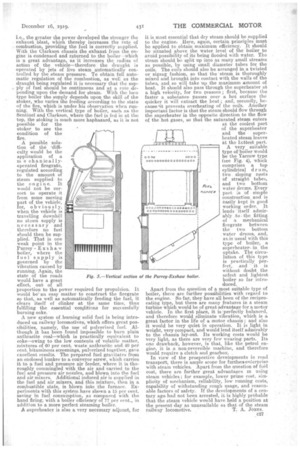

type of'boiler would be the Yarrow type (see Fig. 4), which comprises a top cylindrical drum, two sloping nests Of straight tubes, and two bottom water &inns. Every part is -of simple construction and is easily kept in good working order. It lends • itself admirably .to the fitting, of a mechanical firegrate between the • two bottom water drums, and,

as.is usual with this type of boiler, a superheater-sin the uptake. The circulation of this type is practically perfect, and it is without doubt the safest and lightest boiler so far introduced.

Apart from the question of a most suitable type of boiler, there are further possibilities with regard' to the engine. So far, they have all been of the reciprocating type, but there are many features in a steam turbine which would be of great advantage for a motor vehicle. In the first place, it is ,perfectly balanced, and therefore would eliminate vibration, which is a great factor in the life of a, motor chassis ; and also it would be very quiet in operation. It is light in weight, very compact, and would lend itself admirably to the chassis lay-out. Its working costs would be very light, as there are very few wearing parts. Its one drawback, however, is that, like the petrol engine. it is a non-reversible machine, and therefore would require a clutch and gearbox. ,

In view of the prospective developments in road transport, there is ample scope for further enterprise with steam vehicles. Apart from the question of fuel cost, there are further great advantages in using steam vehicles ; for example, lower prime cost. sins' plioity of mechanism, reliability, low running costs, capability of withstanding rough usage, and reasonable factors of safety.. If the developments of a century ago had not been arrested, it is highly probable that the steam vehicle would have held a position at the present day as unassailable as that of the steam

railway loComotive.. T. A. JONES.