Former dustman Brian Curran had no burning ambition to be

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

a haulier until an irresistible opportunity came along. But 10 years on, he tells David Taylor, if something more exciting turned up he'd close the door on haulage pretty smartly.

H ow often have you seen a haulage boss quoted as saying what a wonderful industry road haulage is, what wonderful people work in it, and how they could not imagine doing anything else? How often have you wondered if

they were telling the whole truth?

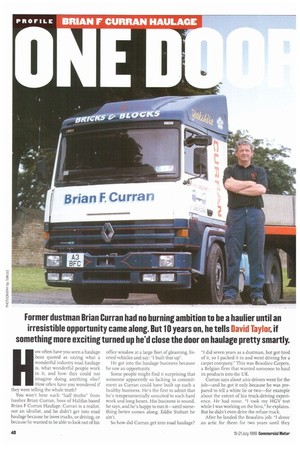

You won't hear such "half truths" from haulier Brian Curran, boss of Halifax-based Brian F Curran Haulage. Curran is a realist, not an idealist, and he didn't get into road haulage because he loves trucks, or driving, or because he wanted to be able to look out of his office window at a large fleet of gleaming, liveried vehicles and say: "I built that up".

He got into the haulage business because he saw an opportunity.

Some people might find it surprising that someone apparently so lacking in commitment as Curran could have built up such a healthy business. He's the first to admit that he's temperamentally unsuited to such hard work and long hours. His business is sound, he says, and he's happy to run it—until something better comes along. Eddie Stobart he ain't.

So how did Curran get into road haulage?

"I did seven years as a dustman, but got tired of it, so I packed it in and went driving for a carpet company." This was Beaulieu Carpets, a Belgian firm that wanted someone to haul its products into the UK.

Curran says about 200 drivers went for the job—and he got it only because he was prepared to tell a white lie or two—for example about the extent of his truck-driving experience. He had none. "I took my HGV test while I was working on the bins," he explains. But he didn't even drive the refuse truck.

After he landed the Beaulieu job: "I drove an artic for them for two years until they decided they didn't need a full-time driver in the UK; it didn't make economic sense for them."

With his HGV licence and two years' experience, you might have expected Curran to go straight into another hauling job. But instead he took a job with local brickmaker Marshalls Clay Products, driving fork-lift trucks on the night shift.

This began to pall after a while. "I was about to get married, and my wife-to-be didn't like the idea of me working nights," he says.

Old-boy network

Then the story takes a surprising turn: Curran called on the old-boy network. A friend from his teenage years, Philip Marshall, was now chief executive of the firm that bears his name and for whom Curran was driving fork-lifts.

"I asked him if he'd sell me a truck," says Curran, with the proviso that the truck came with work! Marshall confirms the story, adding only that Curran received no special treatment just because the two had mixed socially. "But I suppose the fact that we were old friends gave him the courage to approach me directly," says Marshall.

Curran acquired his first truck at Christmas time 1989, a Volvo F7 six-wheel rigid. What made him take the plunge was doing a few day-shifts in the yard. He saw how many trucks came and went in a day (about 150) and thought "there's got to be money in this".

In 1989, there was. That's when the construction boom peaked and brick sales reached an all-time high. From then onwards it was all downhill for the brick industry; sales never returned to their 1989 level. But Curran was lucky it didn't all turn pear-shaped.

Just as he had taken his HGV test while on the bins, Curran studied for his CPC while driving fork-lifts. He got an 0-licence, bought his truck and in March 1990 set up as a contract haulier for Marshalls. He was doing something right, because a year later he added a second six-wheeler and took on his first employee, driver Gary Ayrton—another childhood friend.

Curran has since built up his fleet to five vehicles. Two are in Marshalls' livery and two arc in his own, The fifth is a bit different.

Anxious not to put all his eggs in one basket, Curran was soon on the look-out for something new. He found it, again in Belgium. "A mate of mine who had a heavy haulage and storage business, was having a four-axle extending trailer made in Belgium by Faymonville, and I went over with him one day to see how it was coming on. While we were there, I saw these float glass trailers being made for Saint-Gobain (the French glass giant) and thought 'this is big business'."

Returning to the UK, Curran put out a few feelers, "but there was no interest". This sort of float glass trailer just wasn't used here. Then one day he saw one in the livery of Stoke-on-Trent-based Brit-European, It turned out that Brit-European was running the special glass trailers out of a depot in Calais. Curran contacted the depot and asked how they'd like a haulier operating one of these trailers in the UK. Feedback was positive, so he got on the line to Faymonville and fixed himself up with a used trailer.

As far as he's aware, Curran is still the only UK haulier operating the Faymonville floatglass trailer. Driver Gary Ayrton hauls the frailer with an Iveco tractor in Brit-European livery. Curran's own trailer—damaged in an accident near Cambridge involving a swan— was sold last year to a Spanish operator, and Curran now hauls one of Brit-European's trailers.

Parlous state

Today, Curran has a steady business going and he works hard—if only for the sake of his drivers, for whom he expresses immense admiration and respect. But though, like any haulier, he smarts at UK diesel prices, he's not the type to lament the parlous state of the industry. He's pretty blasé about it.

He says he'd jack it in tomorrow if something more exciting cropped up.

Married to Bernadette, a midwife who "isn't interested one iota" in his business; with a daughter (Siobhan, 7) who wants to be a vet, and son (Kieran, to) who wants to be a marine biologist, Curran doesn't feel he has to hand the business down.

"They can decide for themselves. I'd hate to force them into something they didn't like," he says. When be was a kid he wanted to be a fireman. After leaving school he actually applied but "never heard anything back", and didn't pursue it. Instead, he trained as a joiner, a craft for which he soon found he had no aptitude. So he went on the bins.

"It's the best job I ever had—only 2o hours a week and the pay's good." says Curran. Running your own haulage business takes a much heavier toll. At only 41, Curran's already asking himself—after a particularly hard day—why he does it.

He's not the sort to moan, though. After all, who knows—something else might turn up.