THE REVOLUTION IN RAILWAY RATES.

Page 51

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

How the New Classification Affects the Commodities which Interest the Road Haulier. The New Schedules of Rates and Their Application.

'MOW that the Railway Rates Tribunal has provision.1.11 ally approved the schedules of standard charges submitted by the companies in pursuance of the provisions of the Railways Act of 1921 (subject to a few minor adjustments which have been found necessary to meet specific representations of the traders), the moment seems opportune for a general survey of the position.

The advent of the "appointed day "—that is, the day to be fixed by the Tribunal for the change-over from the present conditions to the new—will witness a revolution of the first magnitude, and it is not too much to say that neither the railway companies nor the traders can visualize exactly how each will be affected. It is, however, abundantly evident that, with the very best of intentions and with every desire to adjust the position, there is bound to be a considerable amount of chaos. The whole of the existing arrangements are being swept away ; new rate bases fixed upon an entirely new classification and the position profoundly affected by the modifications in the chargeable distances which are being substituted.

The " Depressed " Class Rates.

The existing arrangements date back to the General Rates Revision of 1891 and 1892, when the Railway Clearing House Classification was, broadly speaking, accepted as the standard classification, and when maximum charges were provided in respect of each class based upon mileage. There was, however, one Important modification in that the level of the rates, at that time fixed, varied with the distance. The scales were graduated and, as the distance increased, the charge per ton-mile correspondingly diminished, so long as the traffic remained on the system of a single company. Where traffic had to be transferred to another railway company, the graduation was broken and the charging recommenced on the highest level.

These rates, however, were only maxima, and, within the limit of the statutory powers, the companies had a discretion which was largely exercised, and a very wide range of rates are in existence which are far below the powers of the companies—due allowance, of course, being made for the appropriate increases which have since been added. These rates are known as " depressed " class rates, and have been the subject of a very long discussion before the Tribunal, inasmuch as the traders have felt that the new arrangements will wipe out their present advantages under these rates and result in formidable increases as and from the "appointed day."

Many statements were submitted in evidence which showed that the total increase over the pre-war rates would in many cases exceed 100 per cent. Nor was the evidence in this connection challenged by the companies themselves, but the problem of adjusting widely varying rate bases to a schedule of standard charges has been found insoluble, and the Rates Tribunal, In their recently issued report, suggest that the adjustments should be made, where necessary, by an extension of the principle of conceding " exceptional " rates.

It may be assumed that neither the railway companies nor the traders are greatly enamoured of the prospects awaiting them in the immediate future, hut the whole situation has got beyond them, and the ponderous machinery devised by the Railways Act of 1921 is beating out a result which is likely to be unsatisfactory to all concerned.

A brief retrospect of the circumstances which have led to the present position are necessary. In 1920, following the period of Government control, the Government considered the whole question and deemed the

time opportune for a general inquiry into railway questions, including, inter aim, railway rates, fares and charges and the principles by which they should be governed. The Minister of Transport at that time, Sir Eric Geddes, issued his questionnaire to the traders and, as a result of the answers received, appointed the Rates Advisory Committee, with the following terms of reference :—

The Scope of the Enquiry.

"The Minister having determined that a complete revision of the rates, fares, dues, tolls and other charges on the railways a the United Kingdom is necessary, the committee are desired to advise and report at the earliest practicable date as to :—

" (1) The principles which should govern the fixing of tolls, rates and charges for the carriage of merchandise by freight and passenger train and for other services.

"(2) The classification of merchandise traffic and the particular rates, charges and tolls to be charged thereon and for the services rendered by the railways.

"(3) The rates and charges to be charged for parcels, perishable merchandise and other traffic conveyed by passenger train or similar service, including special services in connection with such traffic."

This inquiry covered the whole field of railway activity in its relation to the traders, and its report (Cmd. 1,098) formed the basis upon which Sir Eric Geddes framed the Railways Act of 1921. To this committee belongs the responsibility for (1) recommending and determining the pew classification extending the present eight classes to twenty-one. (2) Sweeping away the prineible of maximum rates and substituting standard rates, from which there is to be no variation either upwards or downwards. (3) The adoption of the principle of continuous mileage and for the profound modifications which have been made in the " conditions " upon which railway companies carry mer

• chandise.

The Classification of Goods and Loads.

The Rates Advisory Committee was authorized on the lines of its report to prepare a revised classification, their findings in this connection being as follow:— " The classification should be divided into a greater number of classes than now exists, and shonld take account of the quantity of goods constituting a consignment, a lower classification being accorded to goods forwarded in large quantities than to the same goods when sent in smaller quantities.

"Exceptional rates cannot be abolished, but every effort should be made to incorporate as many of the exceptional rates as possible in the standard rates by the adoption of conditions as to quantity in the classifications."

The factors determining the recommendation were :— (a) That an extended classification would give a greater flexibility, and (b) would provide a readier means for the elimination of exceptional rates by providing medial schedules approximating the existing level of the exceptional rates.

Whilst these considerations were admirable in theory they broke down in their application to facts. So far as classification for variations in tonnage was concerned, the companies were unwilling to apply the principle, except to a very limited extent ; and, as for the second factor, there was such a wide disparity in the levels of the exceptional rates that it was impossible to devise any intermediate classes which would satisfactorily absorb them. None the less, the companies duly submitted their proposals in accordance with these recommendations. The existing eight classes were extended to twenty-one and the traders were invited to submit their objections.

It was inevitable, in view of the numerous displacements rendered necessary by the change, that a big volume of protest would arise, and the Tribunal was overwhelmed with objections, which rendered it necessary to create a negotiating committee of traders' representatives to co-ordinate and discuss the objections with the railway companies, leaving the Tribunal to adjudicate upon those items on which agreement was found to be impossible.

A vast amount of work was involved, and it cannot be pretended that the result is in any way satisfactory or that the new classification commends itself to either the traders or the railways.

It is instructive to remark in this connection that Sir Ralph Wedgwood (one of the principal witnesses for the railway companies) has recently expressed his opinion to a meeting of railway students. His fear is that the new classification will be a handicap to the companies in their fight with road interests. Remarking that the road carrier is not greatly concerned with an elaborate classification, but is prepared to take widely differing types of merchandise at the same rate, he visualizes the time when it will be necessary for railway companies similarly to accept blocks of traffic at a uniform rate, although it appears that the new classification stands in the way of the adoption of such a practice.

For the information of road carriers we give below a skeleton outline showing how the new classification compares with the old, and indicating where the medial classes have been inserted.

The relation of the new classes to the existing classes as shown in the present general classification is as under :— It is to be noted that in the lower classes the weight minima have been increased, thus automatically forcing up the rates for the existing minima. For instance, traffic in Class A, which at the present time is subject to a minimum of four tons, will actually be in Class 7, which is the lowest division of Class C for 4-ton parcels, and, similarly, traffic in Class C, which has a minimum of two tons, will lose the advantage of the subdivisions, Classes 7, 8 and 9, unless forwarded in future in 4-ton lots.

c30 The new classification is a complicated compilation of some 265 pages, and the greatest difficulty will be experienced by traders in accommodating their arrangements in accordance with its provisions.. The fol lowing instances will illustrate this:— Class Machines and machinery, in cases ... ... 10 Machines and machinery, not packed, min.

1 ton per truck ...

Engines, steam, hydraulic or internal-combus12 tion : 5 tons ... 16 Engines, steam, hydraulic or internal-combus18 tion as follow :—Not in cases or frames...

Machines fitted up, e.o.h.p.:— • • • 18 In cases or frames ...

Not in cases or frames ... 19 Machines complete or in parts as under:— In cases ... 20 Each of these entries is accompanied with formidable lists of the particular machines or parts of machines to which the specific entries are applicable, but it may be safely predicted that the greatest difficulty will be found in determining under which particular classification a specific consignment falls. We think the road hauliers may congratulate themselves on the fact that they are not bound by any such elaborate and cramping arrangements. For the information of readers who may be interested in knowing the specific classes allocated to principal commodities, we give below the more important, commencing at Class 11, which is probably the level at which road transport becomes actively competitive:— Class 11.

Ale and porter, candles and tapers, cider and perry, cylinders (iron or steel), fruit pulp (4 tons), oils (not dangerous) and grease, paper, soap, sugar and saccharine, spelter, mineral waters.

Class 12.

Earthenware and glass (common), brass (not machined), cattle food (in casks or sacks), copper and brass scrap, apples and pears, fuel economizers, hemp (4 tons), machines and machinery as above, including electrical plant, presses, shafts and axles.

Class 13.

Bronze (cast, not machined), builders' implements, castings (not machined), copper casts (not machined), disinfectants (solid), fish, handles and shafts (wood), motorcar rims, mouldings and beadings, radiators (castiron), seeds, stampings and pressings, superheaters, telegraph stores, timber (rough satvn), vinegar, valves (iron or steel), wheels (iron or steel).

Class 14.

Bacon and ham, butter, cheese, dried fruits, lard, cranes, electrical plant, engines, condensed milk, brass nuts, bolts and rivets, brass tubes.

Class 15.

Biscuits and confectionery, blacking, boilers, cocoa, copper, wrought, earthenware and fireclay ware (not packed, 2 tons), preserves and peel, tobacco Ieaf.

Class 16.

Accumulators (dry), aeroplane parts, aluminium (cast, not machined), asbestos, axles, battery parts, bedsteads (metallic), boot heels and soles, studs and protectors and stiffeners, bread, buckets, chemicals, china, cisterns and tanks, cordials in casks, crucibles, doors (armoured), drums and casks (metal), dyes and dye products, electric apparatus, foods, forges, fruit (soft), gas plant and scrubbers, glass (sheet), gums, hollow-ware (cast-iron, nested), leather (heavy mechanical), mattresses (woven wire), motorcar body

parts, newspapers and periodicals, safes, sauces, skylights, stoves, grates, heaters and ranges (common), woodware (domestic).

Class 17.

Castings (brass, copper or bronze), forgings (brass, copper or bronze), nickel and nickel alloys, offal for food, printed matter.

Class 18.

Basins and stands (lavatory), baths, beds and bedding, belts and belting, bicycle accessories (also wheels), bins, blinds, books, boots and shoes, boxes (A arious), bunks, cages. carts (children's or folding), chairs (common or folding), cordials, drapery, eggs, fenders and curbs, fixtures (shop or office), foods (compounded), frames, furniture (school), glass, plate and glassware, groceries (mixed), hardware, metalware and tinware, machine guns, harness and saddlery, hats and caps, hollow-ware, houses and huts (portable), indiarubber and gutta-percha goods, lamps and lanterns (common), mantelpieces, meters, nuts and nut kernels, perambulators with wheels off, patterns (travellers'), pumps, seats (wood or metal, common), wines and spirits, stoves, grates, heaters and ranges (polished), tea.

Class 19.

Animals (live), bedsteads (wooden), meat, lamps (electric or motor), wheels (coach or carriage), woodwork, water heaters.

aass 20.

Bath-chairs. basket-work, bicycles and tricycles (small, on own wheels), cigars, cinema apparatus, clocks, carriages, essences, figures and ornaments, furniture, glass (cut or silvered), gramophones, harmoniums, organs and musical instruments, motor horns, looking-glasses and lustres, drugs, motorcycles, silica ware.

Class 21.

Goldleaf (liquid or precipitate), gold articles, platinum and platinum articles, silver and silver articles, statuary.

This list will indicate the broad lines of the new classification and will serve to guide the road haulier in adjusting himself to the new rates when they come into operation.

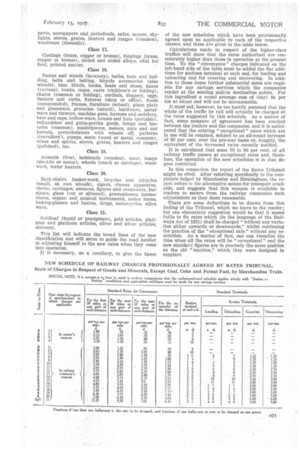

It is necessary, as a corollary, to give the bases of the new schedules which have been provisionally agreed upon as applicable to each of the respective classes, and these are given in the table below.

Calculations made in respect of the higher-class traffics will show that the rates authorized are considerably higher than those in operation at the present time. To the "conveyance" charges indicated on the left-hand side of the table must be added the fiat additions for stations terminal at each end, for loading and unloading and for covering and uncovering. In addition to these items further substantial sums are requisite for any cartage services which the companies render at the sending and/or destination points. For this ingredient a round average sum of (say) 4s. per ton at eitder end will not be unreasonable.

It must not, however, be too hastily assumed that the whole of the traffic by rail will actually be charged at the rates suggested by this schedule. As a matter of fact, some measure of agreement has been reached between the traders and the companies, and it is anticipated that the existing " exceptional " rates which are in use will be retained, subject to an all-round increase of 60 per cent. over the pre-war basis or, roughly, the equivalent of the increased rates recently notified.

It is calculated that some 70 to 80 per cent, of all railway traffic passes at exceptional rates and, therefore, the operation of the new schedules is in that degree restricted.

In this connection the report of the Rates Tribunal might be cited. After referring specifically to the complaints lodged by Manchester and Birmingham, the report refers to the alternative means for transport available, and suggests that this weapon is available to traders to secure from the railway companies such adjustments as they deem reasonable.

There are some deductions to be drawn from this finding of the Tribunal, which we leave to the reader ; but one elementary suggestion would be that it seems futile to fix rates which (in the language of the Railways Act of 1921) shall be charged "without any variation either upwards or downwards," whilst continuing the practice of the "exceptional rate" without any restriction. As a matter of fact, one can visualize the time when all the rates will be " exceptional " and the new standard figures are in precisely the same position as the old "maxima," which they were designed to supplant.