A SMALL ANSWER TO A BIG PROBLEN

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IN Great Britain alone there must be a considerable number of local authorities who find a full-size mechanical road sweeper somewhat large and expensive to operate in relation to the total road mileage which they are responsible for cleaning over the course of a year, yet at the same time complete manual sweeping is obviously out of the question. For such areas the oovious answer is a small, mechanical sweeper of reasonable initial cost and low operational cost, and this explains the continued demand, both in this country and overseas, for the Yorkshire Litterlifter, an example of which I recently tested in Leeds.

Before conducting my own tests, however, I spent some time at Ossett in the company of Mr. J. K. Garlick, M.I.Mun.E., A.M.I.Struct.E., the Borough Surveyor, who has been operating a Litterlifter since November, 1959, at which time it replaced a considerably larger machine which had been costing 25s. per hour to operate. Mr. Garlick's operating costs for the 1961-62 year show the equivalent figure with the Litterlifter to have been 13s. 6d. per hour based on a total of l,537.5 sweeping hours for that period. Expressed in another way, this is equivalent to an annual cost of £22 17s. 6d. per channel mile, the total mileage of county and district roads for which Mr. Garlick's department is responsible being 22-61 (45-22 channel miles).

The operating costs (excluding depreciation) for the Ossett Litterlifter for the 1961/62 period totalled £1,037 12s. 6d., made up as follows; insurance and licence, £32 5s. 5d.; repairs, £126 5s, 8d.; operator's wages (including 25 per cent on-cost), £684 19s. 3d.; brushes, £134 I5s. 11d.; diesel fuel, £49 2s. 9d.; and materials, £10 3s. 6d. It will be seen that the charges for mechanical repairs are somewhat on the high side—indeed, Mr. Garlick's records show that for the year just ended they are more than £100 higher than the figures quoted above—and this has been mainly owing to bad luck with the Litterlifter's engine, which it is hoped that the recent purchase of a new power unit will now cure. The repair charges also include expenditure on tyres and a certain amount of work occasioned by some of the chain-sprocket drives shearing.

Mr. Garlick told me that a big advantage of the Litterlifter compared with the much larger machine he had been using previously was that its utilization was higher as it needed less time off the road for cleaning, maintenance and so forth, up to 1,800 annual working hours being obtainable compared with 1,300 hours (in round figures) with a fullsize sweeper, whilst 1,650 hours could certainly be counted on under normal conditions with the Yorkshire machine. Covering the district by itself, the Ossett Litterlifter has an average daily pick-up of 5 tons, and this figure could possibly be improved upon with a larger hopper, a limitation with the present machine being that, when light refuse and dust is being collected, the hopper fills up very quickly, although the weight of material may not be particularly great.

The operational advantages of a machine the size of the Litterlifter—it is only 12-ft. long and 4-ft. 6-in, wide— are quite considerable, and often a Litterlifter can be used to supplement the heavy work carried out by larger equipment. For example, because it has gutter brushes on each side and because the driver sits centrally, it can sweep either side of the road in either direction with equal ease, therefore one-way streets present no problems. l's small width presents less obstruction to normal traffic, whilst its tight turning circle enables it to closely follow the line of small-radius kerbs and to zig-zag in and out of parked vehicles almost as nimbly as a man with a broom.

Its compact dimensions also ease the garaging problem, whilst the use of steel-wire-bristle main and gutter brushes considerably reduces brush-replacement costs and the downtime needed when the brushes have to be changed. An average figure for the life of the Litterlifter's main brush is six weeks, compared with about 10 days for a larger machine, and annual brush costs are usually about 30 per cent of those associated with a full-size sweeper. Incidentally, Mr. Garlick's experience has shown that a complete set of brushes takes about 90 minutes to change, though adjustment of the main-brush bristle holders is quite simple and is carried out daily by the Litterlifter's operator.

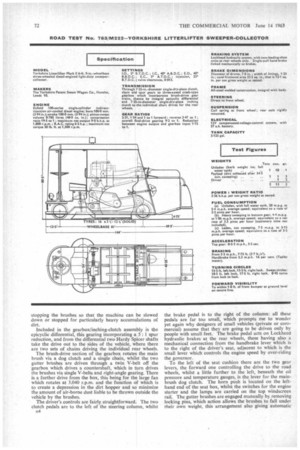

Although -the Litterlifter has been on the market for several years, its design is sufficiently interesting to warrant a brief description. The standard power unit is an Enfield 100-series single-cylinder four-stroke air-cooled diesel, the J.A.P. petrol engine at one time offered now rarely being called for. The Enfield engine is interesting for its extensive use of aluminium-alloy _castings, which are used for the crankcase, cylinder and cylinder head: the cylinder has an iron liner cast into it, whilst the head has iron combustion chamber, valve seats, and inlet and exhaust ports cast in. CAN. fuel-injection equipment is employed, and the crankshaft carries a centrifugal governor, the action of which can be over-ridden by a driver's hand control. Cooling is provided by a fan integral with the flywheel, and I2V starting equipment is fitted. The maximum governed speed of the engine is 1,800 r.p.m., and the crankshaft carries a Borg and Beck A.6 7-25-in.-diameter clutch, whence the drive is taken via a chain, spur gears and a short universally jointed shaft into the special three-speed gearbox which provides drives for the rear wheels and the brushes, the two separate sets of sliding gears providing identical ratios except that there is no reverse for the brushes. The drive to the road wheels then passes through another Borg and Beck A.6 clutch which is used for inching and is operated by a pedal to the left of the main clutch pedal: the purpose of this clutch is to disconnect the drive to the road wheels without stopping the brushes so that the machine can be slowed down or stopped for particularly heavy accumulations of dirt.

Included in the gearbox/inching-clutch assembly is the epicyclic differential, this gearing incorporating a 5: I spur reduction, and from the differential two Hardy Spicer shafts take the drive out to the sides of the vehicle, where there are two sets of chains driving the individual rear wheels.

The brush-drive section of the gearbox rotates the main brush via a dog clutch and a single chain, whilst the two gutter brushes are driven through a twin V-belt off the gearbox which drives a countershaft, which in turn drives the brushes via single V-belts and right-angle gearing. There is a further drive from the box, this being for the large fan which rotates at 3,040 r.p.m. and the function of which is to create a depression in the dirt hopper and so minimize the amount of air-borne dust liable to be thrown outside the vehicle by the brushes.

The driver's controls are fairly. straightforward. The two clutch pedals arc to the left of the steering column, whilst D4 the brake pedal is to the right of the column: all these pedals are far too small, which prompts me to wonder yet again why designers of small vehicles (private or commercial) assume that they are going to be driven only by people with small feet. The brake pedal acts on Lockheed hydraulic brakes at the rear wheels, these having also a mechanical connection from the handbrake lever which is to the right of the driver's seat, adjacent to which is the small lever which controls the engine speed by over-riding the governor. To the left of the seat cushion there are the two gear levers, the forward one controlling the drive to the road wheels, whilst a little further to the left, beneath the oil pressure and temperature gauges, is the lever for the mainbrush dog clutch. The horn push is located on the lefthand end of the seat box, whilst the switches for the engine starter and the lamps are carried on the top windscreen rail. The gutter brushes are engaged manually by removing locking pins, which action allows the brushes to fall under their own weight, this arrangement also giving automatic compensation for wear. When not required for sweeping, the brush spindles are pulled up as far as they will go and the locking pins inserted.

The general layout of the Litterlifter can be seen in the drawings reproduced in the data panel, from which it will be observed that the gutter brushes throw the dirt into the path of the 3-ft,-wide main brush, which in turn lifts the dirt and throws it into a hopper, assisted by the depression created by the suction fan. Air is drawn by the fan from the hopper through a straw filter contained in the lid of the hopper, and after passing through the fan this air is discharged to the atmosphere through a secondary filter made of Terylene. Behind the hopper there is a 22,5-gal. water tank which supplies the belt-driven water pump, which in turn feeds the atomizing water-sprinkler outlets• necessary to prevent the creation of excessive dust. The sprinklers are controlled by a tap located to the right of the steering column.

When the hopper is full, discharging is carried out by releasing two securing catches and then operating a Dowty hydraulic pump by hand, this extending rams on each side of the machine and so tipping the hopper up. The hopper is lowered by gravity on opening the release valve incor porated in the pump. q.

While in Ossett I witnessed a typical sweep carried out by Brindley Jackson along a road close to the depot. The gutters in this road held considerable quantities of very fine grit, coal dust and ashes, and Brindley used first gear on the drive to the road wheels and second gear on the brush drive, this being the usual gearing combination for all but the very heaviest conditions, and giving a travelling speed equivalent to a comfortable walking pace. After 1.25 miles of sweeping the hopper was full, and a weighbridge check showed that 14 cwt. had been collected. The actual time that the Litterlifter was sweeping totalled 37 minutes, but the journey time was longer as it had been necessary to refill the water tank once from a road hydrant (the Ossett machine carries a stand pipe, etc., in a tray on its roof for this purpose), whilst further stops were necessitated by the need to keep raking the dirt to the rear of the hopper, failure to do this resulting in dirt falling back on to the road.

Generally the machine was sweeping fairly satisfactorily, though a tendency was noticed for it to leave a faint trail along the line of the outer side brush, this being most marked where either the camber of the road was severe or the gutter rather deep, conditions for which the Litterlifter was never really designed. A certain amount of dust was thrown up at times also, but rarely was this sufficient to cause annoyance to pavement users. Although, as I was to find out later, the engine noise is deafening for the driver of the machine—after all, a single-cylinder air-cooled diesel only a few inches away from the back of one's head is a difficult thing to silence—the noise level as heard in the street was not particularly bad, although 1 would hesitate to recommend the Litterlifter for night sweeping in residential areas.

The machine used during the second day was a Yorkshire demonstrator. With this 1 carried out a typical sweeping cycle while making accurate checks on the amount of fuel used and the time occupied. First, the machine was weighed with the water and fuel tanks full, following which a distance of one mile was covered to represent conditions when the sweeper is travelling between its depot and the area to be swept. This run was made in top gear at engine governed speed, and the machine was able to maintain its top speed of 5.3 m.p.h. throughout the ,journey.

Where we had finished up turned outl to be a rather dirty part of Hunslet, but the Yorkshire driver elected to use the same combination of gears as Brindley Jackson had used the previous day. Again some of the roads swept were heavily cambered and had deep gutters, which resulted in a tendency for the Litterlifter to leave a trail, whilst another tendency was for the back end of the machine to slide towards the kerb. A further snag was the frequent need to keep raking the collected dirt to the rear of the hopper whilst, after a stop had been made for this purpose on a I-in-10 gradient. the Litterlifter jibbed at getting away again, the symptoms suggesting clutch slip. This could only have been through maladjustment, however, because each of the clutches is rated for a capacity of 60 lb-ft.--twice the engine's output. The total distance covered while sweeping was 1.1 mile, this occupying an overall time of 48 minutes, of which 34.5 minutes were spent actually sweeping. The water-tank capacity, incidentally, was sufficient to keep the sprays working for 45 minutes.

At the end of the sweep it was obvious that the hopper was fairly full, and this was verified later on a weighbridge after the water tank had been refilled, 1 ton 1-75 cwt. having been collected. Before weighing the machine, however, a third consumption run was made to simulate the vehicle travelling from the sweeping area to the tip, and this again was covered at maximum speed.

The three sets of consumption figures obtained are detailed in the accompanying data panel, from which it will be seen that the Litterlifter is by no means heavy on fuel. As for its cleaning efficiency, observations made during its sweeping run showed that it would pick up most things, from small strips of paper to half-bricks, and including food cans, a large piece of bent wire and a flattened cardboard carton measuring about 1 ft. square. Very little dust was thrown up by the machine, but there again the dirt being collected was nothing like as fine as that experienced in Ossett the previous day. So far as road camber is concerned, on fairly flat stretches of carriageway the Litterlifter swept very thoroughly without any tail-end sliding and a clean path 4-ft. 3-in.-wide was left behind. The engine of this particular vehicle warranted a black mark for the excessive emission of smoke when pulling hard before the governor had cut in.

From the driver's angle I suppose the kindest thing that can be said about the Litterlifter is that it is more pleasant to handle than a broom! Like most things, though, once one is used to it, it doesn't seem so bad after all. The noise is the main problem, but the steering also can be a bit frightening initially as it is completely direct, meaning that one full turn of the steering wheel turns the front wheels through 360. On the Ossett machine the steering was excessively heavy, but this effect was not so noticeable with the Yorkshire demonstrator, with the result that the latter vehicle was easier to control and to keep at a constant distance from the kerb. In both machines the engine vibration was excessive, and the requisite brake-pedal effort far too high. .

All things considered, however, the Yorkshire Litterlifter is an economical way of filling a quite considerable gap in the municipal world. Its list price in primer, including flashing direction indicators and the standard cab with doors at each side. is £1,875. and painting and lettering can be carried out by the manufacturers for a further £55.