THE FREE-WHEEL IN THE TRANSMISSION LINE.

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

As an Aid to Gear-changing, the Free-wheel Clutch is now Being Considered for the Motor Vehicle.

Alm since the earliest days of the sliding gear 11.1we have been promised that, in the near future, we should have some better way Of changing from speed to speed. The fulfilment of this promise has been so long delayed that many have lost hope, and in some cases the opinion has been expressed that we shall never attain a materially better method. Others have declared that the slight skill necessary in changing from speed to speed adds to the pleasure of driving, and that to make it more automatic would be like giving an accomplished pianist a -player-piano, or giving a barber a safety razor.

There may be some truth in this view so far as the vehicle which is strictly a private car is con earned, and We do not feel prepared to dispute it, but so far as the commercial vehicle goes, we are pre

pared , to say that such a view is absurd. Heavy vehicles and loads, clutches that must necessarily be large and, consequently, retain their impetus, heavy gears, heavy clutch springs and drivers who are often clumsy, circumscribe the conditions that usually prevail in the commercial vehicle, and all these conditions are directly oPPOsed. to the use of the now universal sliding gear. One has only to ride in buses, where the drivers are well trained, to notice that even these Men are none, too certain in making a clean change. Careful inspection of the debris in the repair shops where commercial vehicles are dealt with will prove that some better change-speed gear is wanted.

At the present moment several efforts are being made to improve the change-speed gear, but strange to say most of the efforts are ha the direction of the private ear and not where it is more needed, in the commercial vehicle.

If we leave out that class of gear where epicyelic gears, with brakes to arrest the. reactionary elements, are employed, we find that most of the efforts are in the direction of disconnecting the drive which is transmitted to the gearbox by the propeller shaft and the forward movement of the vehicle. In most of the designs a free-wheel is employed behind the gearbox, so that the instant that the engine is disconnected from the gearbox by withdrawing the dutch the gears are no longer influenced by the rate of forward movement of the vehicle, and it is to deal with the probability of this device solving the problem that this article is written.

The fitting of a clutch of some kind behind the gearbox so that the gears that have to be changed shall not be influenced by the forward Movement of the vehicle and can, therefore, be changed with greater ease, is by no means a new idea. It has been tried many times in the past, but in all probability there were so many other things at that time which required the attention of the designer that this matter was shelved. It must not, however, be thought that this shelving of the idea in any way preyed that the principle was not sound and worthy of further investigation. By those most competent to judge it has been pointed to as a probable solution of the problem, and the idea has been repeatedly mentioned in The Commercial Motor as being one of the most promising lines for thought.

Many of the earlier experimenters in this direction appeared to overlook the fact that a clutch which is situated behind the gearbox has to transmit, roughly, four times the torque of the ordinary clutch in front of the gearbox. When one considers that the ordinary clutch is none too satisfactory the difficulty of designing a clutch of the kind to transmit the heavy torque of the lower gears will be realized. wheel behind the gearbox, and we know of no fewer than five separate and independent investigations of this principle which are now being carried out. Although little in the way of detail information is available at the present moment we have gathered the following facts and hope in the near future to be able to give full details of most of them after road trials have been made.

The devices referred to above fire, first, the Sandburg. This device has been 'fully described in the motor journals already, so little more can be said, excepting that it consists of a.number of free-wheels mounted so that they can couple the required gear to its shaft when needed, the free-wheels being formed by the introduc tion of skewed rollers between male and female cones. The Joseph device consists of a special free-wheel situated behind the gearbox, and a provision whereby the free-wheel action can be converted into a positive -drive in both directions, a slight braking effect being brought to bear on the revolving shafts after both front and rear clutches have discon tinned their drive, this brake on the shaft speed acting in the manner of, a clutch stop.

The A.C. (Acedes) mechanism somewhat resembles the Joseph gear, but few details are available.

The Wardinan also appears to be much on the same lines. Mr. Wardnian (of the Vulcan =Motor and Engineering Co., Ltd., and Lea and Francis, Ltd,) demonstrated his gear to us one day last week and handed over the wheel of his . car to us during a traffic 'stop in the heart of London. When the traffic began again to move we engaged second gear and let in the clutch and, whilst the car was on the move, found that we . could waggle the gearlever through the gate and in and out of any gear position without any clashing of the gears or feeling any obstruction. At high speed, even, we changed from fourth to first, first to third, back to first and again into fourth just as if there were no teeth on the gearwheels to be meshed.

The Farley hails from America, and the free-wheel in this case is situated in one of the operating gears, so that only the lay-shaft is freed from the influence of the rear axle shafts. In this, like the others, the free-wheel can be converted into a positive drive at will. A description of this gear can be seen in the page of The .Clommereial Motor which deals with patents in the present issue.

General Remarks on the Subject. , Should any of the above devices make good in connection with private cars it will encourage efforts in the direction of the application of the principle to commercial vehicles, but it cannot be taken asProof positive that the plan will prove equally successful on the heavier vehicle. We can see several things which should be borne in mind by those who are contemplating applying the free-wheel principle in the transmission of the heavier class of vehicle, and a 'few tips gathered from the experience of those who have traversed the thorny path before may be of use.

The term " free-wheel " is a modern name for the equivalent of a ratchet—a unidirectional driving device. A later and more polite word, "valve,"bas been applied r343 to the same device; but, call it what you like, it is practically a ratchet in action, although it is usually of the silent type, where jamming action instead of the engagement of a pawl in teeth -is employed.

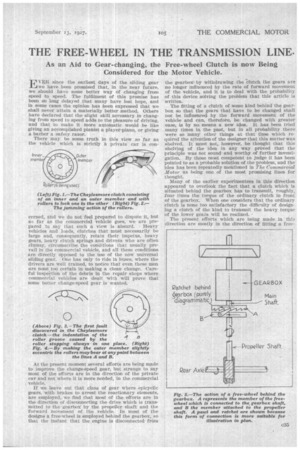

The commonest and most generally adopted form of the jamming type is that once known as the " Cheylsmore " clutch, Figs. 1 to A. This type of clutch has been used for a great variety of engineering purposes, and when heavy duty has been imposed upon it it lias in many cases been found that the pressure of the rollers, always coming on the same spot on the incline, cause a depression, as shown in Fig. 3. When this occurred the jamming action becameuncertain and in time failed altogether. By an accidental piece of bad workmanship the outer surface in one instance was not concentric with the axle on which it revolved and the result was that the rollers impinged at anywhere between the two puts A and B, Fig 4. The formation of depressions at the. point of impinging was thus lirevented and the idea was at once protected by letters patent (which milk have expirecl long ago).

We are afraid that many of the present experimenters are under the impression that by using a free-wheel of the jamming type they are employing a device that will take up its drive without shock and permit of fi gentle engagement of the two shafts to be coupled. We can assure them that nothing of the sort can be expected, for when the rollers of a free-wheel are prevented from jamming by any device (such as a partial rotation of a cage holding the, rollers -back) and then allowed to engage, a hammer blow occurs, and it is very: doubtful whether the heavy parts of a _ commercial vehicle could he set in motion by allowing the Milers to jam, . after being held . out of engagement -for sufficient time to allow the gears to 'come to rest. It may be said that a driver should not hold a free-wheel out . long enough for this to happen, but drivers do not always do what they should.

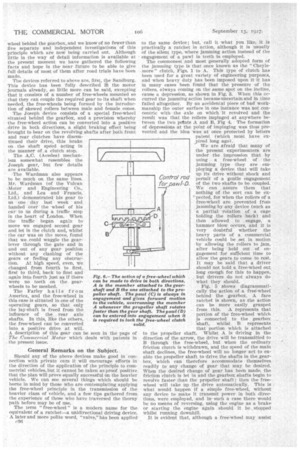

Fig. 5 shows diagrammatically the action of. a free-wheel behind the gearbox. A face ratchet is shown, as the action can be more easily grasped from this. A represents that portion of the free-wheel which is connected to the gearbox "Shaft, whilst B represents that portion which is attached to the propeller shaft. Whilst A is driving in the direction of the arrow, the drive will be transmitted to B through the free-wheel, but when the ordinary friction clutch is withdrawn, and the speed of the main shaft declineS, the free-wheel will no longer act to enable the propeller shaft to drive the shafts in the„.gearbox, which can therefore accommodate themselves readily to any change of gear that may he desired. When the desired change of gear has been made, the friction clutch is let in and the gearbox shafts begin to revolve faster than the propeller shaft.; then the freewheel will take up the drive automatically. This is what would happen if a simple freewheel, without any device to make it transmit power in both directions, were employed, and in-. such a case there would be no means of reversing, using the engine as a brake or starting . the engine again should it be _stopped whilst running downhill.

It is evident that, although a free-wheel may assist

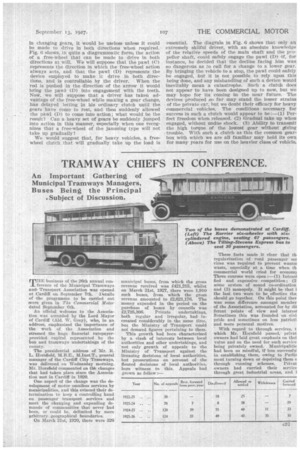

in changing gears, it would be useless unless it could be made to drive in both directions when required., Fig. 0 shows, in quite a diagrammatic form; the action of a free-wheel that can be made to drive in both directions at will. We will suppose that the pawl (C) represents the direction in which the freewheel action always acts, and that the pawl (D) represents the device employed to make it drive in both directions, and is controllable by the driver. When the rod is pushed in the direction of the arrow it would bring the pawl(D) into engagement with the teeth. No*, we will suppose that a driver has taken advantage of the free-wheel while making a gear change, has delayed letting, in his ordinary clutch until the gears have come to rest, and then suddenly allowed the pawl (D) to come into action; what would be the result? Can a heavy set of gears be suddenly jumped into action in this manner, especially when one recognizes that a free-wheel of the jamming type will not take up gradually?

We would suggest that, for heavy vehicles, a freewheel clutch that will gradually take up the load is essential. The diagrain in Fig. 6 shows that only an extremely skilful driver, with an absolute knowledge of the relative speeds of the main shaft and the pro

peller shaft, could safely engage the pawl (D) for instance, he decided that the decline facing him was. so dangerous as to call for a change to a lower gear. By bringing the vehicle to a stop, the pawl could safely be engaged, but it is not possible to rely upon this being done, and any mishandling of such a device would inevitably mean a catastrophe. Such a clutch does not appear to have been designed up to now, but we may hope for its coming in the near future. The devices produced so far may stand the lesser strains of the private ear, but we doubt their efficacy for heavy commercial vehicles. The conditions necessary for success in such a clutch would appear to be :—(1) Perfect freedom when released. (2) Gradual take up when engaged, without undue shock. (3) Ability to transmit the high torque of the lowest gear without giving trouble. With such a clutch as this the common gearbox with which we are all familiar may hold its own for many years for use on the heavier class of vehicle.