a British premium tractive unit

Page 47

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By D Lloyd BSc

Part 3: Selecting a transmission system

TRANSMISSION includes not only the gearbox but the whole driveline of clutch, gearbox, propshaft, rear axle and rear road wheels, all of which should be considered together; although, for convenience, I am only going to consider possible clutch /gearbox combinations in this section.

Gearboxes are the field of heavy vehicle engineering in which, in my view, British manufacturers are weakest. While both David Brown Gear Industries and Turner Manufacturing are working on heavy-duty gearboxes for 40 tonnes at 8 bhp /tonne these are not yet available. Following the link with the Dana Corporation, Turner Manufacturing will be making Spicer gearboxes at Wolverhampton, but the American transmission manufacturer longer established in Britain is Eaton Corporation which makes gearboxes and rear axles. Fodens also make heavy-duty transmission, so there is a choice of British made units suitable for a premium specification tractive unit, in addition to American and German transmissions.

I would choose fully automatic transmission if money was no object, and the Allison HT 750 made by General Motors is suitable for engines up to 400 bhp. The close-ratio version HT 750 CRD recommended for on-highway use consists of a torque converter coupled to a five-speed constant-mesh gearbox. Ratio spread of the gearbox is 3.19 to 1 and there is a choice of torque converters with stall torque ratios up to 2.8 to 1, giving an effective bottom gear of about 9 to 1.

Drive range selection is similar to automatic transmission on a car with drive, neutral and reverse positions and the additional feature that when "2" or "3" is selected on the quadrant the gearbox still changes automatically between the lowest two or three gears. Position 1 is creeper range. However, a fully automatic transmission is complicated (the HT 750 has seven clutches, six of which are hydraulic-actuated, spring-released, oil cooled, multidisc and self-adjusting) and consequently expensive.

Some British heavY lorries use SelfChanging Gears semi-automatic transmission and the biggest gearbox in the range, the type RV30 8-speed, has a nominal rating of 1000 lb ft but this is subject to the manufacturer's approval of the application, and they do not recommend this transmission for use with the Rolls-Royce Eagle 340 or Cummins NTC 350 engines, as the engine powers are right at the top end of its rating.

So apart from the fully automatic application mentioned, transmission for a premium specification tractive unit is either a torque converter and gearbox or a conventional friction clutch and gearbox multi-speed in the latter case and either range-change or splitter.

The main advantages of a fluid torque converter over a conventional clutch are: (i) Very smooth starting from rest. The converter acts as a slipping clutch and protects the transmission from damage due to sudden torque fluctuations. German experience is that the virtual elimination of clutch failure alone justifies the cost of a torque converter. Easier driving due to reduced gear changing. A friction clutch is used behind the converter for gear changing but, if desired, it can be made automatic, giving two-pedal control.

(iii) The elimination of the splitter or range-change. A five-speed gearbox is sufficient.

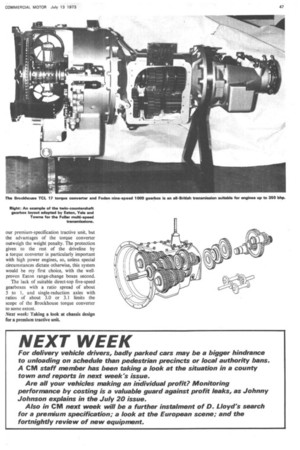

Available torque converters are the Foden /Brockhouse TCL 17 suitable for engines up to 350 bhp and the ZF /Fitchtel iind Sachs models for various engine powers; the WSK 420 caters for 350 bhp engines and the WSK 470 for engines up to 450 bhp.

The method of operation differs slightly in that as engine speed drops the ZF torque converter does not cut in automatically until between 1100 and 1000 rpm, whereas the Foden cuts in at 1600 rpm. Between 1100 and 1800 rpm the ZF torque converter can be brought into operation by means of a kick-down switch. This would be done, for instance, when speed is falling off towards the top of a short hill and in this case the torque converter acts like a splitter gearbox.

Fodens claim that the advantage of the automatic cut-in is that it eliminates the necessity for the driver to decide when the converter shall be used. The 1600 rpm engine speed cut-in point can be varied to suit specific applications and this would be necessary for "our" premium specification tractive unit as the intended engine speed at motorway running speeds is between 1500 and 1600 rpm. The Brockhouse TCL 17 incorporates a temperature switch which cuts out the converter should oil temperature become excessive, and the ZF has a one-way clutch on the input side so that engine braking and /or tow starting is possible. A retarder is under development which will fit between the converter and the separating clutch and adds only 60mm to the length of the transmission. Driving impressions of one of the WSK series torque converters in a 38-tonne vehicle were given in Commercial Motor for December 1 1972 and a road test in Lastauto und Omnibus No. 8/71 of two Magirus Deutz vehicles, one with WSK and one without, showed improved acceleration of between 5 and 10 per cent with the torque converter, and 726 gearchanges on the vehicle with the WSK compared with 993 gearchanges on the vehicle without, over an 800km test route.

Fuel consumption was the same to within per cent, but true fuel consumption with the WSK was slightly less at 25.6 LPU to 26.0 LPU for the vehicle with the mechanical clutch. Disadvantages of torque converters are only the obvious ones of cost and weight. The WSK 420 weighs 210kg which added to 245kg for the 5S-150 gearbox gives 455kg, or 35kg

more than the Allison HT 750.

A cheaper alternative transmission is a friction clutch and multi-speed gearbox and the Eaton RT9509 series range-change gearboxes already used on a number of British 32-ton tractive units with Cummins and Rolls-Royce engines are approved by Eaton for engines up to the Cummins NTC 350. For the Cummins NTA 400 engine the RT 12509 series gearboxes would be necessary. Main gearbox ratios are the same for the 9509 and 12509 series, both direct top or overdrive, but the range-change of the 12509 series is greater at 3.38 to 3.20.

Eaton gearboxes are constant-mesh type but gearchanging is not difficult provided a pull-type clutch with a clutch brake is used. The Lipe-Rollway 15-kin. two-plate clutch with organic facing is suitable and covers the torque range of engines suggested for the premium specification unit.

However, a splitter gearbox has a number of advantages over a range-change, being easier to use in my opinion, particularly when part-loaded, or in city traffic at the sort of road speeds at which the driver is continually having to change the range with a range-change.

Also, in any multi-speed gearbox the percentage steps between the gears should increase towards bottom gear, and it is possible to design a splitter gearbox this way with respect to half the gears, although in Spicer gearboxes, which cover the required torque range, it is not done. The Spicer split-torque (SST) 10-speed gearbox is available in either direct top (SST 1010-2A) or overdrive top (SST 1010-3A) versions and direct top with an aluminium case (SST 1010-4A) which saves 80 lb in weight. Torque capacity is 1000 lb ft, suitable for the Rolls-Royce Eagle 340 or Cummins NTC 350 engines. For the Cummins NTA 400 engine, the Spicer SST-11 gearbox, with 1200 lb ft torque capacity, is an 11-speed splitter, lIth gear being an overdrive recommended for use when the vehicle is running light. Spicer gearboxes are constant-mesh and the Spicer angle-spring clutch, which is pull type (but the clutch brake is extra) could be used with them.

Correct gear ratios are very important in a high-powered vehicle as unsuitable ratios will increase fuel consumption considerably. The requirements are a top gear giving 60 mph for motorway running at the most economical engine speed of between 1500 and 1600 rpm and a bottom gear enabling the vehicle to climb, at maximum weight, the steepest hill likely to be found on a main road. This is 1 in 6 but to give a margin of safety it would be better if a 1 in 5 hill could be climbed.

Making several assumptions, theoretical hill-climbing ability can be calculated and a series of torque curves drawn showing the gradient that can be climbed in each gear for a particular gearbox, axle ratio, tyre size, vehicle weight and engine but, if several combinations of these variables are to be considered, calculation of the maximum hill climbing ability in bottom gear is sufficient.

On the basis of these calculations I have drawn up this table which shows results for 32-ton and 40-tonne vehicles with Cummins NTC 350 and Rolls-Royce Eagle 340 engines.

The figures show that with an overdrive

gearbox it is possible to combine a high top gear with ample hill-climbing ability at 32 tons gross weight, and that with a direct-top gearbox, obtaining a high enough axle ratio could be a problem as 3.36 is the highest (lowest numerically) available ratio with the Eaton 19120 axle. At 40 tonnes gross weight with the ninespeed gearboxes and no torque converter, the options include the same high gear with reduced hill-climbing ability or a lower top gear, which would increase fuel consumption, or the use of the NTA 400 engine.

If a 40-tonne vehicle with the 340 or 350 engine is required to climb a hill steeper than 1 in 5 and run at 60 mph at less than 1600 rpm then a gearbox with a wider ratio spread such as the 13-speed RTO 9513 is necessary. A direct-top gearbox has slightly higher efficiency, but to obtain the high top gear necessary for minimum fuel consumption, as well as reduced noise, engine wear and so on, with available axle ratios, an overdrive gearbox will be necessary in most cases.

It is worth mentioning that gearing for 60 mph at 1500 rpm gives theoretical road speeds of over 80 mph at maximum engine speeds, but any operator who does not think that two endorsements on a licence for speeding is sufficient deterrent can fit a Dana road speed governor!

There is, then, considerable variety in the transmissions that could be used in our premium-specification tractive unit, but the advantages of the torque converter outweigh the weight penalty. The protection given to the rest of the driveline by a torque converter is particularly important with high power engines, so, unless special circumstances dictate otherwise, this system would be my first choice, with the wellproven Eaton range-change boxes second.

The lack of suitable direct-top five-speed gearboxes with a ratio spread of about 5 to 1, and single-reduction axles with ratios of about 3.0 or 3.1 limits the scope of the Brockhouse torque converter to some extent.

Next week: Taking a look at chassis design for a premium tractive unit.