Problems of the

Page 56

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

HAULIER

;ad CARRIER IT takes a long time to persuade a haulier to acknowledge the existence of many of the items of operating and establishment costs, especially when, as is unfortunately so often the case, his knowledge of costs is, to put it mildly, rudimentary. This is actually the sixth article of a series describing a conversation with such a haulier, a conversation in which I endeavoured, by leading questions, to persuade him to discover for himself the existence of those various items of cost. His case, however, is so typical that it justifies being considered at such length, and this series should be filed for ready reference.

An Inadequate Conception of Costs.

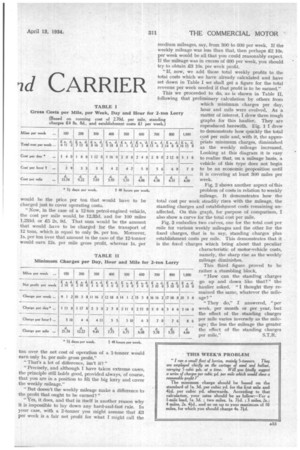

In the story, as told in these six articles, this haulier has, step by step, argued about each of the 10 items of operating cost with the exception of petrol, oil and licence. He has scoffed at the bare idea of the existence of establishment costs, but at length has been persuaded that, in his case, as the operator of a 2-ton lorry, he is involved in expenditure as follows ;—For running costs 2.70d. per mile; standing charges, £4 8s. 8d. per week, and establishment costs, £1 per week.

I have explained to him how these figures must be used to calculate either the cost per mile or the total cost per week, and how those figures vary according to the weekly mileage. I have pointed out that to ascertain the cost per mile he must divide the sum of the standing charges and establishment costs, namely, £5 8s. 8d., by B16 the weekly mileage and add the result to the figure 2.70d., which represents the iunning cost per mile. • To calculate the total cost per week he must multiply the running cost of 2.70d. per mile by the number of miles covered per week and add that to the £5 Ss. 8d. If he wants to know what his cost is per day or per hour, he can easily reckon that from the total cost per week as above ascertained. These figures are set out in detail in Table 1.

The previous article concluded at a point in the conversation where we had, for the moment, agreed to postpone the discussion of what profits should be. It was after agreeing to that postponement that we calculated the figures set out in Table 1 and when that work was completed the question of profits occurred again as was, of course, inevitable.

A Rough Rule for Calculating Profit.

"There is no set rule," was my answer to his question as to what I thought a 2-ton lorry ought to earn as net weekly profit. "I have," I continued, "a rough rule of adding one to the capacity of the vehicle in tons and taking that figure as a basis. For a 2-tormer, for example, a fair profit would be £3 per week, for a 4-tonner £5, for a 7-tonner £8, and so on.

"Generally, the 'rule begins to be inapplicable in connection with the largest size of vehicle, that is to say, 10-12-tonners, although, as a matter of fact, it is sometimes easier to earn a profit with a big vehicle than with a small one."

"How is that?"

"It happens because the class of work that big lorries are engaged upon is usually the conveyance of full loads over long distances. Quotations are generally 'per ton' and it is much cheaper to carry a ton as part of a 12-ton load than it is on a 1-ton lorry."

"I don't quite see that."

" Well, if you will just look at this copy of The Commercial Motor Tables of Operating Costs, I think I shall be able to make it clear. 'Assume, for the sake of argument, that you have a 1-ton lorry which is covering 800 miles per week, and a 12-toriner doing the same mileage. The cost per mile of the 1-ton lorry is 3.41d., so that for 100 miles the cost would be 341d., or 28s. 6d., which

would be the price per ton that .would have to be charged just to cover operating costs.

" Now, in the case of a 12-ton petrol-engined vehicle, the cost per mile would, be 12.33d. and for 100 miles 1,233d. or £5 2s. 9d. That sum would be the amount that would have to be charged for the transport of 12 tons, which is equal to only 9s. per ton. Moreover, 1s, per ton over that amount in the case of the 12-tonner would earn 12s. per mile gross profit, whereas is. per

ton over the net cost of operation of a 1-tonner would earn only 1s. per mile gross profit" "That's a lot of difference, isn't it?"

"Precisely, and although I have taken extreme cases, the principle still holds good, provided always, of course, that you are in a position to fill the big lorry and cover the weekly mileage."

"But doesn't the weekly mileage make a difference to the profit that ought to be earned?"

"Yes, it does, and that in itself is another reason why it is impossible to lay down any hard-and-fast rule. In your case, with a 2-tonner you might assume that £3 per week is a fair net profit for what I might call the medium mileages, say, from 300 to GOO per week. If the weekly mileage was less than that, then perhaps £2 10s. per week would be all that you could reasonably expect. If the mileage was in excess of 900 per week, you should try to obtain £3 10s. per week profit.

"If, now, we add those total weekly profits to the total costs which we have already calculated and have set down in Table I we shall get a figure for the total revenue per week needed if that profit is to be earned."

This we proceeded to do, as is shown in Table II, following that preliminary calculation by others from which minimum charges per day, hour and mile were evolved. As a matter of interest, I drew three rough graphs for this haulier. They are reproduced herewith. Fig. 1 I drew

to demonstrate how quickly the total cost per mile and, with it, the appropriate minimum charges, diminished as the weekly mileage increased. Looking at this diagram it is easy to realize that, on a mileage basis, a vehicle of this type does not begin to be an economic proposition until it is covering at least 300 miles per week.

Fig. 2 shows another aspect of this problem of costs in relation to weekly mileage. It demonstrates how the total cost per week steadily rises with the mileage, the standing charges and establishment costs remaining unaffected. On this graph, for purpose of comparison, I also show a curve for the total cost per mile.

Fig. 3 embodies two curves, one for the total cost per mile for various weekly mileages and the other for the fixed charges, that is to say, standing charges plus establishment costs per mile. This demonstrates that it is the fixed charges which bring about that peculiar characteristic of motor-vehicle costs, namely, the sharp rise as the weekly mileage diminishes.

This third figure proved to be rather a stumbling block.

"How can the standing charges go up and down like that?" the haulier asked. "I thought they remained the same, whatever the mileage?"

"They do," I answered, ." per week, per month or per year, but the effect of the standing charges per mile varies inversely as the mileage ; the less the mileage the greater the effect of the standing charges per mile." S.T.R.