The Evolution of Modern Driving Chains.

Page 14

Page 15

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

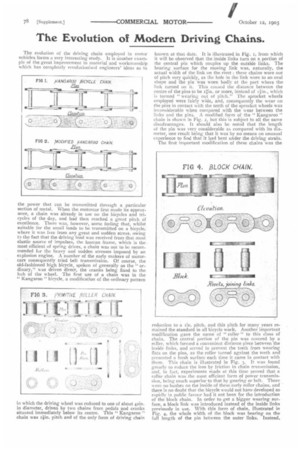

The evolution of the driving chain employed in motor vehicles forms a very interesting study. it is another example of the great improvement in material and workmanship which has completely revolutionised engineers ideas as to the power that can be transmitted through a particular section of metal. When the motorcar first made its appearance, a chain was already in use on the bicycles and tricycles of the day, and had then reached a great pitch of excellence. There was, however, some feeling that, whilst suitable for the small loads to be transmitted on a bicycle, where it was flee from any great and sudden stress, owing La the fact that the driving load was received from that most elastic source of impulses, the human frame, which is the most efficient of spring drives, a chain was not to be recommended fur the heavy and sudden stresses imposed by an explosion engine. A number of the early makers of motorcars consequently tried belt transmission. Of course, the old-fashioned high bicycle, spoken of generally as the " ordinary," was driven direct, the cranks being fixed to the hub of the wheel. The first use of a chain was in the " Kangaroo " bicycle, a modification of the ordinary pattern in which the driving wheel was reduced to one of about 421n. in diameter, driven by two chains from pedals and cranks situated immediately below its centre. This " Kangaroo " chain was Ilin. pitch and of the only form of driving chain

known at that date. It is illustrated in Fig. 1, from which it will be observed that the inside links turn on a portion of the central pin which couples up the outside links. The bearing surface for the moving link was, naturally, the actual width of the link on the rivet these chains wore out of pitch very quickly, as the hole in the link wore to an oval shape and the pin was worn badly at the part where the link turned on it. This caused the distance between the centre of the pins to be 'gin. or more, instead of ain., which termed " wearing out of pitch." The sprocket wheels employed were fairly wide, and, consequently the wear on the pins in contact with the teeth of the sprocket wheels was inconsiderable when compared with the wear between the links and the pins. A modified form of the " Kangaroo " chain is shown in Fig. 2 but this is subject to all the same disadvantages. lt should also be noted that the length of the pin was very considerable as compared with its diameter, one result being that it was by no means an unusual experience to find that it had bent under the driving strain.

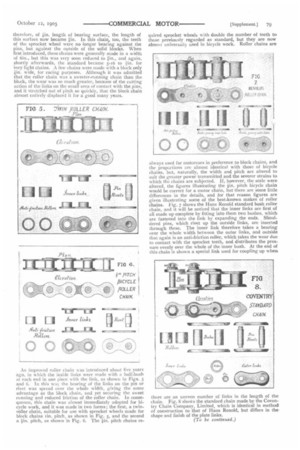

The first important modification of these chains was the reduction to a Lin, pitch, and this pitch for many years remained the standard in all bicycle work. Another important modification gave the name of " roller" to this class of chain. The central portion of the pin was covered by a

whic.h formed a convenient distance piece between the inside links, and served to prevent the teeth from wearing flats on the pins, as the roller turned against the teeth and presented a fresh surface each time it came in contact with them. This chain is illustrated in Fig. 3. It was found greatly to reduce the loss by friction in chain transmission, and, in fact, experiments made at this time proved that a roller chain was the most efficient form of power transmission, being much superior to that by gearing or belt. There were no bushes on the inside of these early roller chains, and there is no doubt that the bicycle would not have developed so rapidly in public favour had it not been for the introduction of the block chain. In order to get a bigger wearing surface, a block link was introduced instead of the inside links previously in use. With this form of chain, illustrated in Fig. 4, the whole width of the block was bearing on the full length of the pin between the outer links. Instead, therefore, of kin. length of bearing surface, the length of this surface now became tin. In this chain, too, the teeth of the sprocket wheel were no longer bearing against the pins, but against the outside of the solid blocks. When first introduced, these chains were generally made in a width of 6in., but this was very soon reduced to gin., and again, shortly afterwards, the standard became 5-16 to ;lin. for very light chains. A few chains were made with a block only tin. wide, for racing purposes. Although it was admitted that the roller chain was a sweeter-running chain than the block, the wear was so much greater, because of the cutting action of the links on the small area of contact with the pins, and it stretched out of pitch so quickly, that the block chain almost entirely displaced it for a good many years.

An improved roller chain was introduced about five years ago, in which the inside links were made with a half-bush at each end in one piece with the link, as shown in Figs. 5 and 6. In this way the bearing of the links on the pin or rivet was spread over the whole width, giving the same advantage as the block chain, and yet securing the sweet running and reduced friction of the roller chain. In consequence, this chain was almost immediately adopted for bicycle work, and it was made in two forms; the first, a twinroller chain, suitable for use with sprocket wheels made for block chains tin. pitch, as shown in Fig. 5, and the second a kin. pitch, as shown in Fig. 6. The tin. pitch chains re quired sprocket wheels with double the number of teeth to those previously regarded as standard, but they are now almost universally used in bicycle work. Roller chains are always used for motorcars in preference to block chains, and the proportions are almost identical with those of bicycle chains, but, naturally, the width and pitch are altered to suit the greater power transmitted and the severer strains to which the chains are subjected. If, however, the scale were altered, the figures illustrating the tin. pitch bicycle chain would be correct for a motor chain, but there are some little differences in the details, and for that reason figures are given illustrating some of the best-known makes of roller chains. Fig. 7 shows the Hans Renold standard bush roller chain, and it will be noticed that the inner links are first of all made up complete by fitting into them two bushes, which are fastened into the link by expanding the ends. Shouldered pins, which rivet up the outside links, are inserted through these. The inner link therefore takes a bearing over the whole width between the outer links, and outside that again is an anti-friction roller, which takes the wear due to contact with the sprocket teeth, and distributes the pressure evenly over the whole of the inner bush. At the end of this chain is shown a special link used for coupling up when

there are an uneven number of links in the length of the chain. Fig. 8 sholks the standard chain made by the Coventry Chain Company, Limited, which is identical in method of construction to that of Hans Renold, but differs in the shape and finish of the plate links.