The Railway's

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

EFFORTS TO STRANGLE ROAD TRANSPORT

in South Africa

TO understand the present position of railway and private road competition in South Africa, and how politics have become a dead weight on railway control, a short reference to affairs during the 21. years previous to 1931 may be useful. When, in 1910, the four existing legislatures of Cape Colony, Transvaal, Natal and Orange Free State agreed to sink provincial interests and become a single Parliamentary body, since called the Union of South Africa, the various private railway systems became state property with the title of the Railways Administration, governed by a board of three highly paid commissioners, these men appointed for life by whatever Government should be in power. The general manager is appointed by consultation between the Board and the Minister of Railways; the late Sir William Hoy was the first general manager.

It was laid down in the Act of Union B38. that the state railways must be run on " business' lines, but that in settling rates for the conveyance of various classes of goods, agricultural produce and commodities must be carried at the lowest possible charges. This has been so well carried out that official figures, given publicity so recently as August, 1931, show that only 9 per cent, of the total volume of traffic is profitable, the other 91 per cent. (agricultural traffic) being moved at a loss.

Agricultural Preference Rates.

The following example shows how the agricultural preference partly reveals why the state railway is estimated to incur a loss of nearly £1,000,000 for the financial year 1931-1932. An importer of 2,000 lb. of rubber tyres for motorbuses or goods vehicles sends them to a consignee 400 miles distant, and the cost of rail carriage is £9 1s. 8d.; between the same starting and terminal places the cost of rail transport for 2,000 lb. of manure is 15s. 11d.

A railway map of South Africa indicates a large number of short branch lines criss-crossing all over the country, linking up the six main lines. From 1910 until 1930 branch lines were laid down at an average rate of 400 miles yearly, and at a capital cost of about £10,000 per mile, or a total of approximately £80,000,000 during the 20 years. On about 10 per cent. of branch lines mixed goods and passenger trains run once da'ily in each direction, but over the remainder the mixed trains run three times weekly each way.

Continued Branch-line Losses.

Not a single mile out of the 8,000 miles of branch lines has ever shown

one penny profit. Up to 1925 the annual branch-line loss was given in the revenue and expenditure accounts, so, perhaps, the growth of the alarming figures is the reason for these losses now being merged in the general statement. There remains the fact that goods rates over branch lines are higher than for main lines.

In 1012 was opened the first road passenger service for a short distance near jape Town, ordinary touring cars being used, and one or two more services were run experimentally, but not until 1924 were real road services for goods regularly scheduled. Such services were the outcome of a settled policy not to construct further branch lines. To-day some hundreds of motorbuses, or mixed passenger and goods vehicles, are employed by the railway, the majority traversing country with farmhouses miles apart, and through tiny villages still more distant from each other.

Some vehicles run 200 miles outward from the nearest rail station and, whilst it is impossible to discover from the annual accounts whether any or all the road services are profitable, it is eel'tam that on at least 90 per cent, of them as heavy losses are incurred as on the branch lines. Had there been any hope of making a fair profit on the routes now conducted by the state railway, private enterprise would have attempted to cater for the demand..

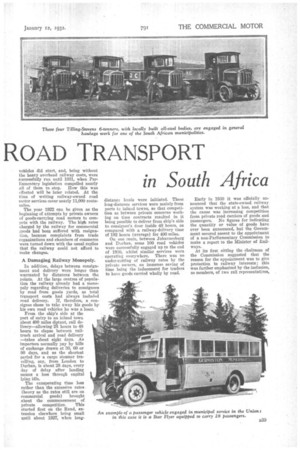

In some districts privately owned vehicles did start, and, being without the heavy overhead railway costs, were successfully run until 1931, when Parliamentary legislation compelled nearly all of them to stop. How this was effected will be later related. At the time of writing railway-owned road motor services cover nearly 11,000 routemiles.

The year 1922 can be given as the beginning of attempts by private owners of goods-carrying road motors to compete with the railway. The high rates charged by the railway for commercial goods had been suffered with resignation, because complaints from trade organizations and chambers of commerce were turned down with the usual replies that the railway could not afford to make changes.

A Damaging Railway Monopoly.

In addition, delays between consignment and delivery were longer than warranted by distances between the points. At the large centres of population the railway already had a monopoly regarding deliveries to consignees by road from goods yards, as total transport costs had always included

road delivery. If, therefore, a consignee chose to take away his goods by his own road vehicles he was a loser. distance hauls were initiated. These long-distance services were mainly from ports to inland towns, so that competition as between private concerns working on time contracts resulted in it being possible to deliver from ship's side to consignee's door inside 48 hours, as compared with a railway-delivery time Of 192 hours (average) for 400 miles.

On one route, between Johannesburg and Durban, some 100 road vehicles were successfully engaged up to the end of 1930, whilst similar services were ; operating everywhere. There was no under-cutting of railway rates by the private owners, an immense saving of time being the inducement for traders to have goods carried wholly by road.

Early in 1930 it was officially announced that the state-owned railway system was working at a loss, and that the cause was increasing competition from private road carriers of goods and passengers. No figures for indicating the quantity or value of goods have ever been announced, but the Government secured assent to the appointment of a non-Parliamentary Commission to make a report to the Minister of Railways.

At its first sitting the chairman of the Commission suggested that the reason for the appointment was to give protection to railway interests; this was further emphasized by the inclusion, as members, of two rail representatives, one agricultural member politically leaning in favour of the Government, and two members of commercial interests. The majority of four against two presented a report that was a foregone conclusion, and, supposed to be based upon that report, came, in due course, the Road Carriers Transportation Act.

This was introduced so soon after publication of the report that it was obvious the new Act had been settled as regards its restrictive clauses weeks or months earlier. Anyway, it was introduced at the tail end of the session in 1930, it being made a " party" measure, and unanimous protest from the opposition party was of no avail. All amendments were voted down and the Bill was rushed through its two concluding stages in the last hours of the last day of the session. It came into force on January 1st, 1931.

There was set up a National Control Board (comprising three members) to hear appeals from 11 local boards (each having three members, including one from the largest local municipality), the latter to adjudicate upon applications for permission to operate in local areas.

A Strangle-hold on Operators.

There is a big difference between these South African boards and the Commissioners appointed last year in Great Britain. In South Africa every operator of both passenger and goods motor vehicles must make applicatipn. There is—for the present time, although conditions are likely to be altered during 1932—exemption from control in a small district surrounding and including Johannesburg. Elsewhere operators must (a) produce the ordinary inlandrevenue licence for a minimum period of six months ; (b) pay an application fee ; (c) pay 7s. 6d. for a permission badge, to be exhibited on the front or B40 near side of the vehicle ; (d) produce an insurance policy against third-party risks for passenger vehicles.

Applications to run from one district to another are heard only by the National Board. Goods lorries are prohibited from carrying persons other than those directly employed by the owners. This is treated as a serious offence ; not merely 'do the culprits (both driver and owner) suffer a heavy fine, but the owner suffers also an immediate cancellation of permission to run the vehicle concerned.

Exacting Railway Demands From Consignors.

Another serious restriction arises out of an ancient Parliamentary clause in a railway Act conferring enormous

financial power upon the railways, and, since February, 1931, this has been enforced. By that clause the railway demands from every consignor a written agreement to forward all goods solely through the medium of rail or road services operated by the Railway Administration. If the consignor sends goods otherwise, even through the mistake of an employee, such consignor is, as a consequence, charged 20s. extra per short ton on whatever he may subsequently forward.

It is this exaction which has been the principal reason for the disappearance during 1931 of many hundreds of

motors. Vast capital sunk in these vehicles by companies and individuals operating "for hire" over short and long. distances has been lost.

On top of this automatic restriction of private enterprise came the refusal by the local control boards of permits for motorbuses and for goods vehicles. On country roads the railway had well covered the ground by its combined passenger and goods vehicles, radiating from terminal points and from inter

vening stations for distances ranging from 15 miles to 200 miles.

To understand, however, the way in which the control boards have quietly suppressed all outside competition, alleged to be against the interests of the railway, a short explanation is desirable. Population is centred mainly in and immediately around a few large towns, such as Cape Town, East London, Port Elizabeth, Durban, Maritiburg, Bloemfontein, Pretoria and Johannesburg, the last-named accounting for at least one-sixth of all the inhabitants of South Africa.

Elsewhere are a few towns averaging some 2,000 people each, and the rest of the place names on the map represent tiny villages, perhaps 40 miles apart. The main and connecting secondary roads between these invariably run parallel with the railway, road and rail being rarely more than five miles apart.

It was between small towns and from them to coastal ports that road-motor companies had worked up encouraging traffic, originating not only from commercial houses, but also from farmers, particularly, wool-growers, who were able to rush wool to the big auction marts at the ports, in response to telephone messages, so as tocatch the top

of the market. The control boards definitely played into the hands of the Railway Administration by refusing permits to all private services running parallel with the rail, on the ground that "the railway is already providing adequate accommodation."

Protection for Municipal Buses.

Action has also been taken against privately owned buses, and, in addition, protection is freely granted to municipally operated buses against private owners. The latter class, when permits are grudgingly issued, is subjected to petty municipal restrictions, such as being allowed to run only during rush hours, or being allotted starting times that secureto municipalities the cream of the traffic. It is now standard practice to refuse a permit for any private bus where the railway has already established a similar service.

A dog-in-the-manger policy has more recently been adopted where the railway has abandoned a service because it was unprofitable. If a private bus owner does apply for a permit along the same road, after withdrawal by the railway, he is informed that "there is no public need, as proved by want of support for the state service."

The net result of the foregoing relation of facts is that to-day, beyond the large town districts, goods and passenger road traffic is finished, other than by cars and railway vehicles.