Good M aintenance Good M aintenance

Page 58

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Pays Dividends

"The Commercial Motor "• Costs Expert Argues That in Normal Conditions it is Economic to Keep a Fleet up to Date and to Dispose of Vehicles After a Comparatively Short Period of Use

READERS of these articles will known that for some years now I have had to preface discussions which involve references to operating costs with a note stipulating that the figures apply only if normal conditions prevail. In dealing with depreciation, for example, I have made my calculations on the assumption that in three or

four years from now the market prices for used vehicles will be much lower than they are to-day.

That consideration comes into the calculation of depreciation in this way. Suppose that a haulier acquires a new vehicle for which he pays £1,150. In calculating the amount which he should set aside for the renewal of his machine, he must first deduct the price of a set of tyres—say E150. Next he deducts what is usually referred to as the residual value, which is the price he will obtain for it when he sells it. That will be when, in his experience of the type of vehicle and the work it is to do, its retention will be costly in respect of growing expenditure on maintenance and

s24

repairs, and the gradually increasing frequency of its visits to the repair shop, involving a growing debit against a vehicle on account of loss of use.

In normal times, residual value is taken to be approximately one-tenth of the value of the vehicle less tyres—in this case one-tenth of £1,000, £100. The net value, the basic figure for the calculation of depreciation is thus £900.

At the time of writing, the return to normal in respect of private cars appears to be almost imminent. It is coming too in commercial vehicles, but not so quickly. The sale of British Road Services vehicles is, I think, likely to expedite, the process. • It seems likely to have the same effect as flooding the market with used machines and the prices will be comparatively low, notwithstanding the bonus of a fiveyear A licence, which is to be given with every vehicle.

I am wondering if when normality is restored, operators will revert to the pre-war practice of replacing their vehicles at the end of two or three or four years' service (the period depending upon the quality of the chassis and the kind of work it is doing), or whether they will decide that that habit has become less economic than it used to he.

General Decline

Assuming that the price of used vehicles will fall, it is probable that the decline will occur throughout the whole range of vehicle ages. That means to say that there will not be any recompense for keeping a vehicle longer than has hitherto been customary.

One factor which may have an effect is the increased activity of the enforcement officers. This is bound to have

a retarding effect on the sale of used vehicles, thus reducing• their market value brought about by fear on the part of

the potential purchaser that the vehicle may have defects which will involve condemnation by the examiner.

There is a principle involved here. The first consideration for any haulier who is to make headway is regularity of service. The older a vehicle becomes, other conditions being equal, the more it is likely to break down on some inconvenient date. By buying new vehicles and by disposing of them after a comparatively little period of use, a haulier minimizes the risk of loss of goodwill because of failure to deliver on time.

Someone reading this may be inclined to ask.who is going to buy used vehicles if this principle and the wisdom of buying new is adopted? The answer can be taken from experience of the days when the habit of disposing of vehicles after two or three years' time was prevalent. I came across many an example in those days where a haulier, known to be in ti e habit of disposing of his vehicles after a comparatively short period, actually had a waiting list of buyers. This argues that the drop in used-vehicle prices is least likely to affect machines sold in such circumstanees. Obviously if the conditions are such as to bring a waiting

list of customers into existence, there is no need to consider diminishing the price demanded and, therefore, broadly speaking, I think there is every justification for continuing to dispose of vehicles after a comparatively brief period.

Apart from this consideration, it pays to keep vehicles up to date. Take the cost of one of the lower-priced range of chassis of 6 tons capacity. The price of the vehicle will be approximately £1,150, say £1,000 net, making allowance foe the cost of tyres. Assume that it is kept for three years, during which period it covers 90,000 miles. If a reasonable amount has been spent on maintenance and if the operator concerned has a reputation for selling his vehicles in good condition, it will probably sell for about £350.

Normally, the amount spent on therunning costs, that is to say petrol, lubricants, tyres, maintenance and depreciation, will total about £4,000. (nearly half that is expenditure on petrol and oil). That figure is taken from "The Commercial Motor" Tables of Operating Costs in which provision is made for maintenance and depreciation based on the whole life of the vehicle.

Under special conditions, the average maintenance cost will be less than that given in the Tables because by selling the vehicle at the mileage quoted, certain impoita.nt items of expenditure will he evaded, particularly a complete overhaul, which, of course; is the biggest individual expense. At a moderate estimate, the saving in maintenance because of that will be 0.70d. per mile. Depreciation is £650 over 90,000 miles, .which is 1.73.d. per mile as against 2.17d., a

saving of 0.44d, per mile. The total saving on those two items is thus 1.14d. per mile, reducing the total running costs from 10.57d. to 9.43d. The total of running costs for the 9a,000 miles thus becomes £3,536, showing a saving of £464 over the three years of operation.

Nor is that all. it is common knowledge that as a chassis ages the expenditure on the other three items of Tanning costs grow more rapidly after two or three years of use. It is practically impossible to indicate a precise figure for this, but an incident was described to me the other day which will serve to illustrate the effect of age alone. One of my haulier friends disagreed with me as to the petrol-consumption figures given in the Tables. He said he could not approach them. I4e was obtaining only 10 m.p.g. from a 2-ton sided lorry. I said that it was so poor that it was obvious that the carburetter was at fault and needed art overhaul. He took my advice and went to the maker of the carburetter, who pointed out that several of the parts were so badly worn that the only satisfactory solution was to replace them. The components were renewed with the result that the petrol consumption was reduced to 1311 m.p.g., equal to a saving of lid. per mile, assuming the price of petrol to be 45. per gallon. The saving on a mileage of 90,000 is £469, to the nearest pound.

FUEL OIL . 264%

"Tantalizing Figure"

Actually, every haulier is aware of the importance of

maintenance in relation to overall costs. Nevertheless, whenever the need arises for investigation into the cost of operating his vehicle his first thought is not for maintenance but to his expenditure on fuel, and he tries to find means for increasing that tantalizing figure of m.p.g. The reason for increasing costs of operation may lie in a variety of causes. Even so, the root is nearly always inefficient maintenance.

It is worthwhile to consider the matter broadly by reference to each of the 10 items of operating cost, namely road fund Lax, wages, garage rent and rates, insurance and interest. Those are the standing charges.. The other five items; the running costs, are expenditure on fuel, lubricants, tyres, maintenance and depreciation.

It is not likely that any room will be found for economy in the five standing charges. Nothing can be done about the tax. Insurance premiums are almost standardized, at !east in relation to small fleets. Bigger operators can usually obtain concessions which come as the result of the ability on the part of the bigger operator to bargain. Apart from that I should regard any attempt to cut insurance, premiums as "penny wise and pound foolish."

Garage rent rarely offers an opportunity for saving; even if it does, the economy is not more than a few _peace per week.' Nothing can be done about interest on first cost ante-. so far as driverP, wages are concerned, they are, of course, determined by law. The biggest single factor affecting 'operating costs is the way in which the vehicles-are driven, and it may well he that one of the operator's first eoncerns would be to check on his drivers with a view to discovering whether they are as good as they ought to be.

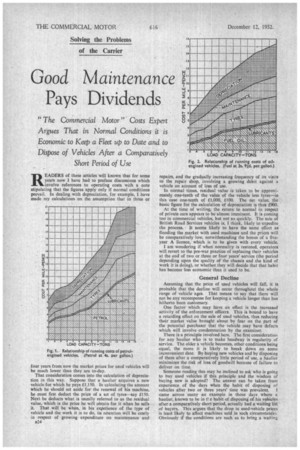

The running costs offer a more fruitful field of economy. In order that the relative importance of each item may be properly appreciated, I have prepared the diagrams which accompany this article. They are based on the figures in the tables. 'Figitre'l shows how the running costs of petrol vehicles compare, item by item.. The first point of interest is how closely the relative importance of the variOus. items adheres to what I might term a fixed relation.The rise in respect of each item with the increase in load capacity

compares closely to the total-increase in operating costs.

Each of the five items continues to bear this same relation to the others throughout; for example, it is clear that the biggest item is petrol consumption and that one of the least significant is lubricating-oil consumption. Figure 2 relates to oilers. The important difference between Figures 1 and 2 is in relation to fuel costs.

' 40 per cent. on Petrol In Figure 3, the relative importance of the five items of running cost of petrol-engined vehicles is shown as perceatages. Average figures for all types of vehicle are used. The expenditure on petrol, it will be observed, is rather more than 40 per cent, of the total, and nearly double that of maintenance. In Figure 4, the corresponding data in relation to oil-engined vehicles are given. Here the fuel cost is only 26.6 per cent. of the whole, maintenance is 20.3 per cent, and depreciation 32 per cent.

It is when the operator comes to consider the factors that bring about excessive fuel consumption that he realizes that his salvation lies in attention to maintenance. What are these factors? Excessive speed, overloading and poor condition of the chassis. It may well be that, whilst appreciating the effects of high-speed operation, he nevertheless accepts it as worthwhile, as the greater his weekly mileage the less his cost per mile, and the more miles he runs the more he is likely to earn. He considers that the game is worth the candle.

No suggestion that the vehicle should not be overloaded ever meets with much response; the operator accepts the fact that by overloading he is increasing his costs, but he takes the view that he is justified so long as his earnings increase, usually at a rate in excess of the extra expense. There is only the item of condition of the chassis left, and there the key to economy is undoubtedly maintenance. There is no doubt that by careful and regular attention to maintenance, actual expenditure under that heading is diminished. Most of what are termed maintenance operations are really quite small jobs and inexpensive if they are carried out regularly.

A good driver will take care of them as a rule, .taking them in his stride, so that as an item of expenditure they will not appear in the balance sheet. The cost will clearly be included in the driver's wages. S.T.R.