To

Page 60

Page 61

Page 62

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Asia Minor SALZBURG

and Beyond

THIS is not a success story because success implies finality and according to the principal character he has not yet finalized his activities. He is an ambitious, restless man who sees potential where others do not and who acts where others would not. His drive will keep him striving for other things—his activities, I fear, will never reach finality.

This story begins for me two years ago when I had a phone call from Mr. Michael Sherif who introduced himself as managing director of Turkish Trading and Transport Co. "I want to transport goods to and from Turkey and perhaps even the Far East; where do I collect a licence to do this?"

Mr. Sherif is of Turkish extraction, and did not quite understand our bureaucracy. I explained to him how our licensing system operated, how he must apply, produce proof of need, satisfy objectors to his application and convince the LA of his requirement and his ability. He was astounded. "To do this I would need a lawyer!" "Precisely," I replied. Perhaps a little inadequate, but all I could think of at the time.

There for the moment our conversation ended but I was sure it would not be the last one. I was right, but a lot happened before I heard again from Mr. Sherif:

His first application for a licence appeared in the Applications and Decisions of the Metropolitan traffic area in August 1967. Following a public inquiry at which there was one objector, Turkish Trading and Transport was granted a licence to carry: "Fresh fruit, vegetables, agricultural produce, foodstuffs, confectionery, fancy goods all from Turkey through Dover to London. Packaging materials, machinery, spare parts, pharmaceutical products all for delivery in Turkey on the instructions of or under contracts with Turkish buyers, baggage and effects of Turkish Government employees from London to Dover."

At first sight not a bad set of conditions—but look again. The traffic was restricted to Turkey and only through Dover from London. In addition, Mr. Sherif gave an undertaking in court that he would not advertise his service. This satisfied his objector.

Three variations to the licence have removed the Dover restriction, added all Middle Eastern and European countries, and permit collection and delivery throughout Great Britain. The contract restriction has also been removed and now the company can advertise. The final variation drew ob

jections from both British Rail and BRS, neither of whom I have ever seen in Europe and who seem unlikely to reach the Middle East for some time yet.

As is common with all new applicants, Mr. Sherif was invited to meet the road /rail negotiating committee. On my advice he accepted the invitation and he tells me that this meeting undoubtedly removed many objections.

Operating in Europe without TIR coverage is almost impossible, especially where journeys take vehicles over more than one border. While the scheme does not guarantee that the vehicle will not be opened by a customs officer en route the likelihood is greatly reduced.

Mr. Sherif required TIR coverage and as the scheme in this country is administered by the two trade associations for the International Road Transport Union, and since he was a professional operator, I put him on to the Road Haulage Association.

At that time the head of the RHA International services committee was R. H. (Dick) Insoll. I believe his conversation with the applicant was along these lines: Sherif: "I want TIR cover."

Insoll: "Are you an RHA member?" :rif: "No."

oil: "Sorry, I can't help you."

:rif: "How do I join?"

oil: "By applying to the area or sub vhere your registered office is situated."

:rif: "Which area meets tonight?"

oil: "The Metropolitan (Western) rea."

nrif: "Right, I'll join there."

oil: "Is your office in that area?"

:rif: "Not at the moment, but it will be tonight!"

was, and he applied and was accepted )ther formality had been completed.

were more to come.

e carriage of goods for hire or reward Tope must be covered by an internaconsignment note. This is a requireof the Convention on the International age of Goods by Road, more corny described as CMR.

rods cannot be carried in Europe under ilier's domestic conditions of carriage [surance. CMR insurance conditions re a liability of £3,500 per ton. Mr.

f found that insurance cover of such rrtions was almost impossible for a operator to obtain. He tells me that through the good offices of Cmdr. P.

continued

Wood RN (Rtd.) did he obtain insurance cover. Apparently Cmdr. Wood is a former naval attache in Turkey and could readily appreciate the potential for road transport in the area.

With the documentation complete the traffic began to move. The first load out to Turkey was pharmaceutical products and the first load back should have been grapes. This was disastrous. The tractive unit broke down, the "reefer" stopped functioning and the net result was the loss of £3,000.

This is the type of event which a Continental operator has to be prepared to encounter. TTT overcame this early setback and was operating again within days.

The variations to the licence widened the scope of the type of traffic and places to which goods could be carried. Even without the assistance of advertising, shipping and forwarding agents were calling daily with part loads. By January 1968 only 50 per cent of the traffic was bound for Turkey; Persia had now become a big customer. However, at this time the licence was confined to Turkey and so the Persian goods had to be consigned to a shipping agent in Istanbul. Mr. Yekta Besen took delivery of the goods and re-consigned them on an ERF for a further 1,700 miles to Tehran. The Persian consignments include electrical equipment, machinery and chemicals. Due to Turkish import restrictions the scope of traffic to Istanbul was found to be limited, so the Persian traffic was more than welcome.

Transfer terminal

Such was the Persian potential that Mr. Sherif set about establishing a transfer terminal in Istanbul. He soon learned that the bureaucracy of his native Turkey made our brand look like watered thlk.

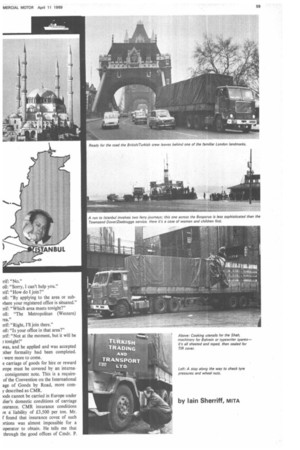

In January 1968 he had applied to the Turkish Ministry of Trading for permission to register a subsidiary of his British company in Turkey. It took innumerable arguments and 12 months to get permission. Now Mr. Yekta Besen manages the transfer terminal. He co-or.dinates movements within the Middle East and arranges back-loads. Part of his task is to generate new business.

Going through TTT's day book is like reading a page from Tales from the Arabian Nights.

Greatcoats to Persian Police Force, cooking and household utensils for Shah of Persia. helicopter parts for Persia. chemicals to Bahrein and Basra, and headache powders to Tehran. The most intriguing entry is 40 tons of razor blades every week to Tehran. This, I understand, is equal to lm. blades a week.

Typewriter paper and spares, outboard motors and diesel engine spares are among the minor items. The largest, I was told, was a complete radio station for Bahrein. This makes frozen eggs to Austria look too easy, but TTT is trying to turn nothing away, with the result that at the moment demand is outstripping supply.

The vast amount of outward traffic from the UK awaiting collection means that ter

minal delays in Turkey have to be kept to the absolute minimum. This is recognized as two days.

The quickest turn-round can be obtained on wine or fruits. Oranges, apples and satsumas which are taken from the orchards in Turkey can be in London markets three days later.

To achieve this each vehicle has two drivers, one British and one Turk; they have sleeper cabs and travel day and night. The longest rest period away from the vehicle other than at Istanbul is on the ferry between Zeebrugge and Dover.

While waiting for the establishment of the transfer terminal, TIT found traffic for Germany, Austria, Bulgaria. Thus the European network was built up.

With quick back-loading established, Mr. Sherif went after a new type of road traffic.

Because of its economic policy Turkey builds its commercial vehicles under licence, and mainly from British manufacturers. Prior to TTT attacking this market these units were sent by conventional shipping methods. They were at least three weeks in transit and the cost was 5 per cent higher than that quoted by Turkish Trading and Transport to British Leyland, for example.

Now the units go out in three to four days from Glasgow to Southern Turkey. I was told that other manufacturers may follow suit.

Obtaining this traffic caused another head-on clash with authority. It must be said here that Mr. Sherif is not a patient man (an opinion with which he is in full agreement).

When he quoted the Albion factory for the job he was 20 per cent dearer than the next highest and was against seven foreign operators. He got the job, but as he had based his rate on 32 tons gross he tried to reduce it by getting special dispensation from the MoT to run at 38 tons gross. He pointed out that he was prepared to travel over routes specified by the MoT and, if necessary, at speeds not in excess of 15 mph between Glasgow and Dover. Almost identical to a special load movement. Of course he was refused.

Waiting

Letters were sent to the Prime Minister, leaders of political parties, the Board of Trade, the Chamber of Commerce. All to no avail; the MoT was considering this amendment to the Construction and Use Regulations and the matter must follow the due processes.

It is frequently claimed that other European operators do run in excess of 32 tons gross in this country because "they have nothing to lose." The MoT very properly would not bend the law and Mr. Sherif and his contemporaries are having to wait.

In this case the cliche "time is money" certainly applied. Operating costs had to be cut, but how and where?

TTT's managing director looked again at his modus operandi and decided that until he could run at 38 tons gross the material from Glasgow to London would require to travel by Freightliner. During the last two months of 1968 the Albion traffic weighed

300 tons. The total Albion traffic for 1969 is estimated at 1,300 tons. During the whole of 1968 TTT's total tonnage was 1,500, but this year it is expected to be treble that.

In support of these expectations there are 74 trailers booked for the Persian Fair. Movement begins at the beginning of July and is programmed to finish in midSeptember. While the inclusion of European traffic on the carrier's licence opened up new territories for TTT, it also produced additional headaches.

German transit permits have been a bone of contention with British operators for some time. These permits are dated and on Middle East runs it is almost impossible to state with any degree of certainty whether a vehicle will be entering Germany at 23.00 hrs or at 01.00 hrs.

Irritation

This, and the fact that there are only 40 permits issued for any one day to British operators, was a real source of irritation with Mr. Sherif. He contends that permits should be issued for a round trip and provided they are transit and not terminal the number should be unlimited. I understand that the Ministry of Transport in London and Newcastle, who issue the permits, have volumes of TTT correspondence on this and other matters!

One problem to be faced when crossing borders is the multiplicity of taxes, and TIT is paying around £800 per trip in taxes outside Britain. One which caused concern was the Yugoslav tax of £100 per vehicle when loaded. This the Ministry of Transport has been successful in eliminating from May of this year.

Between London and Istanbul TTT has a European depot at Liege which was established last January. This offers unlimited bonded and free warehouse space and is operated jointly with Guy Galopin, France.

From this point the company operates a European transfer terminal, collecting loads for the UK and for transport between countries in Europe. Loads are also gathered there for the Middle East and Asia.

However, road transport depots at London, Liege and Istanbul are not the end of things for Mr. Sherif. He is now planning rail, road and sea facilities in Turkey, an agency in Amman (Jordan) and another in' Tehran. His advertisements offer services to Kabul in 21 days, Baghdad 12 days and Basra 13 days, and he offers air facilities to points where the road is temporarily impassable.

Turkish Trading and Transport is not one of Europe's large operators; in fact it is probably one of the smallest. This is the pattern of things in Europe today—a large and growing number of small operators.

The cross-Channel ferry services put vehicles into a network of thousands of miles of road in a few hours. It is a field of operation which offers new opportunities, hard work with commensurate rewards.

How does Mr. Sherif view the prospect of competition?

"Over there", he says, "there's still plenty for everyone."