II CAB COMFORT

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

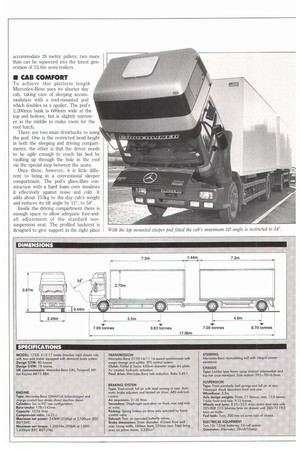

To achieve this platform length Mercedes-Benz uses its shorter day cab, taking care of sleeping accommodation with a roof-mounted pod which doubles as a spoiler. The pod's 2,200mm bunk is 680mm wide at the top and bottom, but is slightly narrower in the middle to make room for the roof hatch.

There are two main drawbacks to using the pod. One is the restricted head height in both the sleeping and driving compartments; the other is that the driver needs to be agile enough to reach his bed by vaulting up through the hole in the roof via the special step between the seats.

Once there, however, it is little different to being in a conventional sleeper compartment. The pod's glass-fibre construction with a hard foam core insulates it effectively against noise and cold. It adds about 155kg to the day cab's weight and reduces its tilt angle by 110, to 54°.

Inside the driving compartment there is enough space to allow adequate fore-andaft adjustment of the standard nonsuspension seat. The profiled backrest is designed to give support in the right place but, in common with other CVs in the Mercedes range, the seat squab is firm with limited suspension qualities.

Considering that our test truck sports nearly 213,000 worth of extras we were surprised by the absence of something as basic as a suspension seat.

Despite what Mercedes-Benz may think of its cab suspension a combination of front, rubber-damped pivot bearings and rear coil springs it can't hope to match the comfort of a good suspension seat set to match the weight of the driver; particularly as the drawbar chassis' long parabolic front springs and rear four-bag air suspension seem designed to be more in sympathy with the load than the person behind the wheel.

However the 1733 driver does enjoy the comfort of a steering wheel that pivots through an arc of 20° to suit most preferences.

The pedal layout could be improved. The natural foot position for the throttle finds the brake pedal, but having made the mistake once it is easy to adjust a little further to the right. Air assistance reduces clutch effort to insignificance. To the left of the driver's seat only the stubby gear selector on top of the engine cowl impedes cross-cab access.

Apart from the obvious differences in cab and wheelbase there is little mecha nical variation between the tractor and drawbar versions of the 1733.

Both use Mercedes' EPS electropneumatic gear-selection system it's standard on Powerliners of 216kW (290hp) and above which sits above the company's own 16-speed synchromesh gearbox. The prime mover's 3.45:1 final drive ratio and 295/80R 22.5 tyres give it the same overall gearing as its tractor stablemate. the toughest of the MIRA test hills. But while the park brake proved powerful enough to hold the vehicle stationary on the 25% (1:4) gradient, initial attempts to move away were foiled by wheelspin. We need look no further than the drive axle for the reason; its almost a tonne down on the permissible weight. With the diffiock engaged the restart was accomplished simply enough.

With a healthy power-to-weight ratio of 7.47kW/tonne (10.18hp/ton), it comes as no surprise that acceleration times are good, although this was not particularly evident in its overall journey times.

Over the motorway sections of our test route the 1733 drawbar combination's overall performance proved to be much the same as many of the high-powered tractive units we have tested recently.

Despite much quicker timed hill climbs we were no faster over the hilliest and most severe part of our route, from Newtown St Boswells to Nevilles Cross. Over the entire 1,180km the 1733 artic proved quicker than the drawbar by 1.5km/h (0.9mph) but at an average of 70.9km/ h (44.1mph) the drawbar is certainly no sluggard.

More significantly, the drawbar used more fuel than its tractive-unit counterpart, despite carrying less weight. It returned an average of 39.291it100km

The pod is quite spacious, but the bunk is cut away slightly in the middle to make more room for the entry hatch.

(7.19mpg) against the tractor's 38.51it/ 100km (7.37mph).

Of course average figures don't tell the whole story, because while the drawbar was thirstier over motorway sections, it was more economical than the 1733 tractor over the slower A-roads and hilly sections. We assume that at slower speeds the drawbar's inferior aerodynamics are less important.

Our road testers haven't exactly been snowed under by drawbar chassis, but the MAN 22.331 drawbar combination we drove back in 1988 allows a more direct comparison between like vehicles. With an average speed of 69.33km/h (43.08mph) and fuel consumption of 41,121it/100km (6.87mpg) it falls just below the performance of the 1733 drawbar. Not surprisingly the 1733 also showed the lowerpowered Dal 2500 drawbar outfit the way home in average speed, but the 2500's overall 38.02lit/100km (7.43mpg) indicates the price that must be paid for that extra power (CM 6 July 1985).