INCENTIVE • BONUSES

Page 34

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Keep Vehicles on the Road

By A. J. Speakman AN ever-increasing number of concerns is instituting group fellowship incentive bonus schemes, either as an innovation or to replace existing piecework schemes which have been found costly in clerical labour and have shown considerable disparity in earnings between individual workers By the incentive bonus system, the shop, or section, is treated as a composite team, and the effort of each worker is related to the total effort of the whole team, expressed a3 o single efficiency factor. Psychologically and economically, therefore, .group fellowship schemes have marked advantages.

Difficulties of Application The problem of applying incentive bonus schemes to transport maintenance is probably the most difficult to be encountered in the entire field of industrial practice, because the amount of work, and its particular nature, cannot always be foreseen. Again, the methods of the individual workers and their personal initiative and skill vary from job to job. Application of time-study technique offers the best method of approach. because it is, primarily, a system of analysis by which labour tools; and materials are all examined under their respective heachagrand-the findings collated to provide the most efficient set-tsp. 'Moreover, lay, determining the normal amount of effort required for each specific task, and type of work it is possible to differentiate between the good and the not-so-good performer and to encourage both to

give of their best. .

No attempt is made to define in detail the principles of time study—it is best treatedas a separate subject—but the reader will readily appreciate the relationship between time study and management control, together with the salient points involved in each function.

The work of transport maintenance can be classified under A32 two main headings—planned maintenance and repair work. The scheme considered here recognizes the inherent difficulties to be encountered in the build-up of each type of work, which is treated separately during the period of

Investigation. The findings are afterwards collated to give a comprehensive picture.

The pre-requisite of maintenance control is the creation of a schedule of work which will define the following functions:—(1) The work to be done; (2) the method to be followed in doing the work; (3) the time required; (4) the personnel required.

The work to be done is the "common denominator" to the four functions outlined above, and it will be apparent that such pre-planning will reduce the " mental " labour of servicing to a minimum and will enable the available labour to be allotted specific tasks of known work value in terms of the man-hours required.

Planned maintenance lends itself to scheduling, because the work is carried out at regular periods, and the nature of the actual service itself is repetitive over those periods. For example, a weekly service may consist largely of inspection of the lubricating system, but will specify in detail the procedure to be followed, such as Change engine oil, top-up oil in gearbox, and grease all steering nipples. Similarly, a monthly service will probably cover items under main headings—for instance, engine, transmission, braking system— each of these sections being broken down into specific inspection operations.

Standard Time for Each Job

The first requirement, therefore, is to schedule the foregoing procedure in such detail that it becomes standard practice. In the same way, the times required to perform each standard service—arrived at by time-study observation —will become standard times for the job.

In this connection it is necessary to define the " standard " time as the time that a man of norma. skill, working at a normal rate would take. The standard time also takes into account the various fatigue factors which have to be considered. such as working position, light and humidity.

Standard time valuza for each job, when multiplied by the frequency of the service, can be expressed as the total manhours required over a given period, such as a week or month, As a corollary, the total man-hours needed for planned maintenance, divided by the total hours when such work can be carried out, will give the number of personnel required over the period.

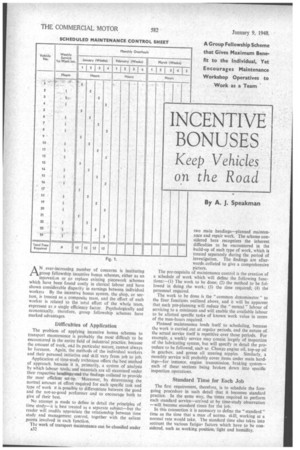

To simplify this somewhat co.nplex form of control and ensure that the work is carried out in accordance with the schedule, it is recommended that a "Scheduled Maintenance Control Sheet" be used, as shown in Fig. I. All relevant information is incorporated in this sheet and, as the time allotted for each type of service is a known factor, it is now possible to use such dines as the basis for planning and deployment of personnel.

Man-hours for Maintenance

Vertical addition of the columns gives the total hours of work per week, which, in the case of weekly services, will be a constant factor Monthly services are staggered, so that they, too, represent a constant time factor, and the sum of both classes of work will then reveal the commitments of the maintenance staff in terms of man-hours required. For example:—

TOTAL STRENGTH, 24 VEHICLES

-Standard Allotted No of Total Man-hours Type. Time per Service Vehicles Required.

Weekly Service 1. Hour X 18 Monthly Service 2 Hours X 6 12 Total 24 21

The sheet can be used for the issue of instructions to the shop and, by comparison with the written entries on the job cards, to establish that the work has been carried out, and the time taken as against time allotted.

To measure the amount of work involved in repairs is always difficult, and it is necessary to assess. the value, in man-hours, of the work that has been performed during a given reference period, say three months. The job cards for all the fitters' work for the previous three months should be analysed to obtain the following information:—(1) Description of the work done; (2) details of spare parts used in the repair; (3) the fitters' time on the job.

The job cards should then be classified under vehicle types, and details of the work performed on each vehicle during the whole period should be abstracted. In making this analysis, work which would come under the category of planned maintenance should be segregated. The total time booked. against planned maintenance jobs can then be compared with the scheduled time and will indicate the state of efficiency on this type of work. • Against each of the repair jobs should be written down an estimated time allowance. These estimates should be made by a qualified member of the supervisory staff and, • if possible, should be checked with the vehicle repairs. manual.

Accounting for Unspecified Work

In many instances more work is carried out on repair orders than is actually detailed on the instruction. This is, of course, just as it should be, because it is the duty of the department to turn out each vehicle in good running order and not to confine itself to rectifying only the specified faults.

It is necessary, therefore, to assess the amount .of this unspecified work, and arrangements can be made to see that all additionat work 'Should. for a period, be written in red ink on the job card. These job cards arc then analysed to show the percentage of unspecified work.

Referring now to the analysis of the three months' cards, the times estimated for each job should be added together and the total increased by the measured percentage of unspecified work. The resulting figure should then represent a reliable assessment of the work value of all the repairs carried out during an average period of three months, it being a not unreasonable assumption that this amount of work will have to be done in any three months. There will inevitably be slack periods and rush periods, but it is considered that in three months both conditions will have been embraced and a fair average will have been shown. Having completed the assessment of repair work and formulated the schedule of planned maintenance, it is necessary to collate the labour requirements under both headings in order to give the total number of workers needed for the shop. The assessed times to which reference is made are based only on mechanics' work and do not include any allowance for assistance by mates and labourers. On the other hand, observation in the shop will show that in all circumstances the proportion of -unskilled to skilled work usually remains constant, say 40-50 per cent., in which case an allowance of one mate to two mechanics will be adequate.

Other work so far not mentioned is supervision by a working charge-hand and shop-cleaning.

Assuming that the reference period shows there are 119 hours per week of repair work and the total man-hours required over the same period for planned maintenance are 21, the team needed can be determined in accordance with the following formula:—

Total man-hours of work. Skilled personnel required = Time available for work.

Example: • Skilled work: Planned maintenance = 21 hours per week.

= 140 hours per week.

If a 40-hour week be in operation, the equation reads as follows:—

Personnel required = 144 = 31 workers 40 hours a week = 140 Supervision by working charge-hand = I worker a: 49 hours a week = 20 140

Mates = — = 70 hours 2 = 2 workers at 40 hours a week •-• 80 Shop cleaning-10 hours Total = 6 workers at 40 hours a week = 240

The team, as shown by this method of assessment is, therefore:— I Charge-hand (50 per cent, of t:rne on supervision). 3 Mechanics.

2 Mates or labourers.

6 Workers at 40 hours a week = 240 hours a week.

Better Maintenance: Fewer Repairs • Using the hypothesis that the quality of maintenance is reflected in the amount of repair work, the efficiency of the fleet is evidenced in its availability for work, and can be expressed as the "vehicle availability factor," determined as follows:— Potential working hours — hours lost due to breakdown

Potential working hours x 100,

A daily return is made, listing each Vehicle that is out of commission and stating the length of time that it was out of use. At the end of the week these figures are totalled and converted to days by dividing the hours by 24. The resulting figure is then related to the total number of vehicles multiplied by five days. An example of the computation is given below:—

instances where the repair department is not responsible, such as waiting for spares or withdrawn for planned maintenance.

The application of the vehicle availability factor is a method of control of maintenance work where time is 'lost through breakdowns of vehicles. During these stoppages it is a maintenance function to repair the vehicle, so that running can be resumed, and it is logical to offer an inducement to maintenance workers to reduce to a minimum the period of time lost.

For this reason and because of the obvious difficulty of measuring all classes of maintenance work, the problems of paying an incentive bonus are apparent. The vehicle availability factor, however, provides a basis which is both fair and easily understood by all concerned.

If a basic availability be set, it is possible to pay a bonus factor for increases in efficiency between basic and 100 per cent. The basic availability factor is found by examination of time lost due to breakdowns over a given period, and the curve shown in Fig. 2 illustrates the bonus factors which

can be earned for improved availabilities through a range of 3 per cent.

Although a straight-line method of calculating the bonus from basic to 100 per cent, would be the easier operation, this is neither equitable nor does it offer sufficient incentive to the maintenance staff to achieve the maximum efficiency. Thus, the greatest incentive should occur when the goal of 100 per cent. availability is nearest achievement and examination of the curve in Fig. 2 will illustrate this point. The following formula is used to construct the curve:— 40 Y 2 (100—X)— Y where 40 is a constant determined by the maximum bonus to be paid for 100 per cent, vehicle availability. Y = the difference between basic availability and the actual availability obtained. X = the basic availability for the fleet. If actual vehicle availability be 98.3 per cent, and basic vehicle availability 97 per cent., X equals 97 per cent. and Y 98.3 per cent., minus 97 per cent. (1.3 per cent.).

40(1.3) 52 — = 11% 2(100 —97) — 1.3 4.7

Hidden Lost Time It is generally agreed that maintenance, more than any othei type of work, is subject to hidden lost time. On the other hand, it is a fundamental principle of any bonus scheme that payment can be made only for productive work and productive time. In this case, the vehicle availability factor constitutes the unit of measurement, and, as a corollary, only productive time taken to maintain those vehicles can be compared with the time allotted for servicing them.

However workers are usually nervous about booking lost time and some foremen certainly do not help in the matter, is they look on such entries as a reflection upon their own supervision. The very nature of the work makes a certain amount of non-productive time an inherent contingency of the job itself and no disgrace attaches to it. The salient point c2

is to know how much of the total time taken by the team is productive and non-productive.

In connection with planned maintenance, reference has been made to the factors in determining the standard team for the job. Six workers are mentioned in the example, and, carrying the matter a stage further, we can say that the man-hours required per week are 6 x 40= 240. It is suggested, therefore, that when the hours taken exceed the hours allotted, the bonus factor should be adjusted in accordance with the following formula:—

Allotted hours (100 4 bonus factor x ) 100 Actual hours

For example, if the allotted hours be 240, the actual hours 260, and the bonus tactor 11 per cent., then corrected bonus factor is:— (100 14 11 x 2-40 ) — 100 = 2.5 per cent. 260

Suppose, however, that in the 260 hours booked 20 hours of waiting time are hidden. If they had been booked as non-productive time, the team would have kept within the allotted hours, although only 92.3 per cent, of the time booked would have been productive. In this case the 1 teatn would be paid — x 92.3 .-10 per cent.

100 It will be apparent from the foregoing examples that booking non-productive time, where it occurs, is encouraged.

Workers Must be Convinced

The foregoing methods of control are comprehensive, and may, on that account, appear complicated. The ultimate success, however, of any bonus schemedepends on its integrity and the method of presentation to the workers. It is necessary to state both the task and the performance in such a way that it can be understood by all concerned and so that any member of the team can, should he wish to do so, compute his own bonus.

An incentive bonus board of the type shown in Fig. 3

should be exhibited in the shop. Great importance is attached to this . method of presentation, as it forms the link. between management and workers, and is the "bonus contract" in operation. The board carries all relevant information and space is provided lor the schedule of work, the vehicle availability factors, and the bonus conditions.

The bonus conditions comprise the agreement between management and workers at the inception of the ,scheme, such as:—Bonus is conditional upon the schedule of work being carried out, the use of job-cards, and the shop being kept clean, etc.

Whilst the scheme may not apply in its entirety to all cases, it has many points of application to fit individual circumstances.