OPERATION OUTBACK

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

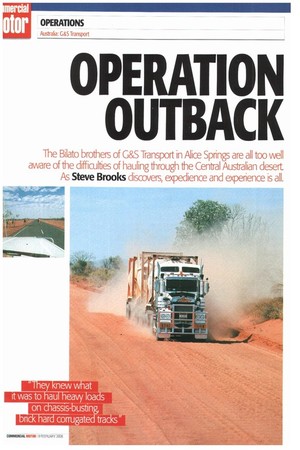

The Bilato brothers of G&S Transport in Alice Springs are all too well aware of the drfficukies of hauling through the Central Australian desert

As Steve Brooks discovers, expedience and experience is all.

When the three Bilato brothers. Robert,John and Frank, bought G&S Transport from Greg and Sue Schlein in I995,they had no illusions about what they were getting into.

They already knew what it was to spend day after seamless day behind the wheel of a truck pulling a string of trailers.They knew what it was to haul heavy loads on chassis-busting. brick-hard corrugated tracks that politicians and other dreamers routinely referred to as roads.They knew what it was to spend 'rest' days under trucks and trailers fixing and improving things in a hid to make the next trip better than the last.

And they'd seen enough and learned enough to know that hauling roadtrains through the outback of Central Australia was no fast path to wealth. At least, not in this part of the world, where the virtue of patience can be as valuable as the will to work when it comes to turning sweat and struggle into something resembling a reward.

But above all they knew that this was what they wanted to do: to own and operate their own business, relying on their own effort and their own initiative, and eventually to get back a bit more than they put in.

Mechanical respect and hard work If they knew a lot before they ever bought the business, it was because they'd been taught well along the way. First, there was their Italian father, What he gave them,apart from childhood days in his Mack, was a respect for things mechanical and a powerful work ethic—the same work ethic that marked so many immigrants who decided to call Darwin and Austra lia's 'Top End' home.

Then there was a man named Jim Cooper.

This was the Jim Cooper whose initiative and determination have created the largest and arguably the most innovative roadtrain outfit in Australia, running some of the largest truck and trailer combinations on the face of the globe. GulfTransport. Bulkhaul and Roadtrains of Australia are all part of the Cooper conglomerate. And after securing their trades— Robert is a diesel mechanic. John and Frank are electricians—each of the brothers spent several seasons in the Gulf Transport operation.

Valuable lessons were learned at this time,John Bilato explains— lessons about trucks. transport. and the wisdom that fosters long-term survival in remote regions: "What came across working with Cooper was that you have to take a long-term approach. Equipment is a long-term investment and it takes time to make money out of trucks. It's a philosophy that works.

"They were hard days and he could be a tough bugger sometimes hut we learned a lot working for him,even though Gulf was a fairly little show back then." he adds. "I've never regretted a day's work I did for Jim Cooper and I'm proud of what I did there.

"That's what's so good about trucksit's measured by the man, not the money."

A decade on,G&STransport runs nine prime movers and about 60 trailers, with 10 permanent drivers on the books including the three brothers.Cat-powered Kenworths are the trucks of choice; the trailer fleet is a mix of flatbeds. tippers and skellies.This reflects an operation of diverse loadings to mining interests and isolated communities that are scattered across the vast sweep of Australia's scorched red heart.

With eldest brother Robert in Karratha (Western Australia) running another operation and youngest brother Frank in the workshop. it's up to John to explain the G&S workload.The hulk of it involves hauling ISO container loads of lime and cement along the gruelling Tanami Road to The Granites goldmine.550km north-west of Alice Springs. But it isn't the firm's only work. "We're only a small outfit compared with some, but we like to think we're making it happen," he says. "There isn't much we haven't hauled into the desert at one time or another."

Flatbed and tipper loads of goods and bulk commodities to outback roadworks and construction projects in remote Aboriginal communities make up a significant portion of the fleet's workload.

Desert roads take their toll

No matter what the load, it is invariably hauled over desert roads and tracks that inflict a heavy price on equipment if maintenance standards wane or the man behind the wheel takes conditions for granted.

And while history and hardship have shown the Bilato brothers time and again that heavyspec Kenworths such as the T65() and C501 are the most resilient survivors of big loads and had roads. John confirms:"Out here you can break anything without trying too hard, no matter what it is." If one road typifies the unforgiving nature of outback desert arteries, it is the infamous Tanami Road. Spearing off the Stuart Highway 20km or so north of Alice

Springs, the Tanami carves across 900km of seared, ageless desert before ending at Hall's Creek in Western Australia's Southern Kimberley region.

In both reputation and reality it is a brutal track, creased by shattering corrugations and hidden slivers of tyre-shredding rocks. It's a place where tyre pressures of trucks and trailers are dropped to around 55psi in a bid to soften the ceaseless pounding on man and machine, and where speed on the dirt is generally limited to less than 60km/h. "Sometimes you can run a bit quicker but not too often," John Bilato commenK"It depends on the conditions, but it's surprising how things can change."

At first, however, the run from Alice Springs is on good asphalt with the only obstacle being the long steady climb out of Alice up to the Tanami turn-off.The first 180km or so is of a high quality with several wide overtaking sections and an extremely impressive stretch of new sealed road that stops a few kilometres short ofTilmouth Roadhouse. From here on, though, the track reverts to type,justifying its reputation as a rough, raw gouge on the face of an isolated landscape.

Over the years,with traffic volumes to mining and indigenous communities increasing, t he Tanami Road has become something of a political football.Various parties agree that greater investment in maintenance and new asphalt is required, but in such a vote-poor province, little more than minor concessions appear to be delivered.

"It's still a terrible road and all the political promises for theTanami have either come to nothing or have been marginal at hest,' John Bilato reports. He points out that just 18km of asphalt have been added to the Tanami road in

the past 10 years. At that rate it would take almost 30 years to add just another 50km of sealed road.

As for the road's ongoing effect on equipment, he finds it easy to quantify: "Repair and maintenance costs running into the Tanami can he as much as 30% higher than running on the bitumen."

Tough and critical

Meanwhile, lite goes on. Despite its battering influence on men and machines, the Tanami's role as a lifeline to remote communities and mining ventures is perhaps more critical than ever before.

At the same time, with increasing streams of tourists seeking the solace and space of Australia's remote regions (particularly during the cooler months), the pressures on drivers are becoming greater too. It's a subject which is close to John Bilato's heart, and one that extends far beyond the Tanami.

"There's no question this sort of work demands a particular type of driver," he remarks."A high-quality driver can make the business and a had one can break it. It's the same everywhere and it's been that way for a longtime.

"But these days there are plenty of operators who want it all straight away and push drivers logo quicker than they probably should. Or at least that's howl see it." he says, again recounting the early lessons that taught the value of taking a long-term approach to ensure survival and ultimate success in the roadtrain business.

"Everyone now talks about productivity and cost-efficiency, and that's fine to a point. But the same push on trucks and drivers that happened with B-trains is now being applied to the operation of roadtrains in the Territory and Western Australia. Given the size and weights of roadtrains, particularly triples and quads. I can't see how that can be a good thing for the drivers, the gear,or anything else — including the transport industry.

"It isn't so much the case where we operate; the Tanami dictates what you can and can't do. But you go on any asphalt road and the pressure is on to do 100km/h everywhere," John Bilato comments."' t's as if everyone wants everything right now— but if our trucks are down to 40.50 or 60km/h it's because of road conditions. And conditions should also dictate how a bloke drives on a good road. Drivers shouldn' be asked or expected to do any more than drive at a pace that suits them, the load they'rt carrying and the conditions at the time. And too many people seem to forget that it takes a long time to get experience in the way a road train behaves, particularly triples and quads.

"Good.experienced drivers are just too hard to get. and if they're pushed too hard they'll eventually go somewhere else —or worse still, they'll get out of the industry altogether.They're too hard to replace and what you get then is probably someone who doesn't have enough experience and hasn't had the opportunity to learn the right way because he's been thrown in at the deep end and told in no uncertain terms to be somewhere at a certain time."

These are bloody big trucks John Bilato is quiet for a moment, then adds: "People seem to forget that roadtrain triples and quads are bloody big trucks:I-here isn't much margin for error and mistakes are usually big ones. We've already seen a few am that's a few too many.

"But there's this mentality dictating that 100km takes one hour and that's it. What the people pushing this fail to realise or remembi is that problems can happen.conditions can change or a driver can just get drowsy and need asleep. But these days there's pressurel push harder and drive faster to get somewhei in a set driving time.

"Sooner or later something gives and it's usually the driver," he concludes."Maybe some people should remember that the journey comes before the destination." •