Leyland -Verheul single-deck bus

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by R. D. Cater, AMInstBE

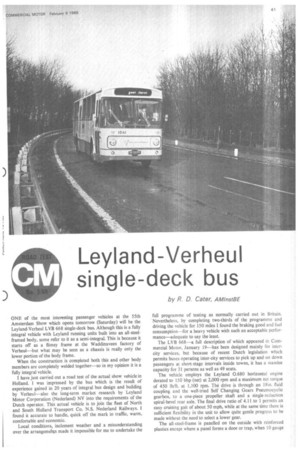

ONE of the most interesting passenger vehicles at the 55th Amsterdam Show which opens tomorrow (Saturday) will be the Leyland-Verheul LVB 668 single-deck bus. Although this is a fully integral vehicle with Leyland running units built into an all-steelframed body, some refer to it as a semi-integral. This is because it starts off as a flimsy frame at the Waddinxveen factory of Verheul—but what may be seen as a chassis is really only the lower portion of the body frame.

When the construction is completed both this and other body members are completely welded together—so in my opinion it is a fully integral vehicle.

I have just carried out a road test of the actual show vehicle in Holland. I was impressed by the bus which is the result of experience gained in 20 years of integral bus design and building by Verheul—also the long-term market research by Leyland Motor Corporation (Nederland) NV into the requirements of the Dutch operator. This actual vehicle is to join the fleet of North and South Holland Transport Co. N.S. Nederland Railways. I found it accurate to handle, quick off the mark in traffic, warm, comfortable and economic.

Local conditions, inclement weather and a misunderstanding over the arrangemehts made it impossible for me to undertake the full programme of testing as normally carried out in Britain. Nevertheless, by completing two-thirds of the programme and driving the vehicle for 150 miles I found the braking good and fuel consumption—for a heavy vehicle with such an acceptable performance—adequate to say the least.

The LVB 668—a full description of which appeared in Commercial Motor, January 19—has been designed mainly for intercity services, but because of recent Dutch legislation which permits buses operating inter-city services to pick up and set down passengers at short-stage intervals inside towns, it has a standee capacity for 31 persons as well as 49 seats.

The vehicle employs the Leyland 0.680 horizontal engine &rated to 150 bhp (net) at 2,000 rpm and a maximum net torque of 450 lb/ft, at 1,100 rpm. The drive is through an 18in. fluid coupling and the well-tried Self Changing Gears Pneumocyclic gearbox, to a one-piece propeller shaft and a single-reduction spiral-bevel rear axle. The final drive ratio of 4.11 to 1 permits an easy cruising gait of about 50 mph, while at the same time there is sufficient flexibility in the unit to allow quite gentle progress to be made without the need to select a lower gear.

The all-steel-frame is panelled on the outside with reinforced plastics except where a panel forms a door or trap, when 10 gauge

aluminium is used. On the inside, plastics laminates are used throughout for the panelling and one of the features of the vehicle is that the body is insulated between the two skins with a 1.5in. thick blanket of closed-cell polyurethane. This has the double effect of reducing drumming in the bodywork and assisting the heating system to do its job.

Power steering, using the ZF Kugelmutter integral steering box, produces easy handling when manoeuvring at low speed in close quarters and delightfully accurate control when travelling at moderate or high speeds. Full air brakes—separate circuits feed the front and rear axles—produce more than adequate stopping power and hardly anything in the way of fade.

The design of the Verheul body permits slim window pillars to be used. The main strength of the body comes from an extremely stiff assembly in the lower panels which takes the form of a lattice girder fabricated from pressed steel channels of various sections. This assembly is supplemented by the cant-rail which is formed by two pressings welded back-to-back and which completes a side frame offering a beam depth of nearly 6ft.

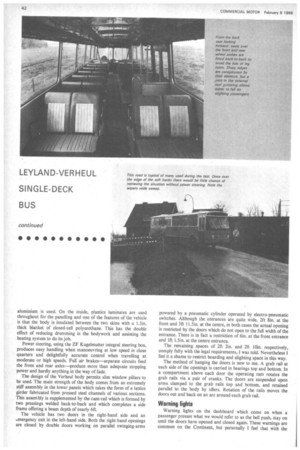

The vehicle has two doors in the right-hand side and an anergency exit in the left-hand side. Both the right-hand openings are closed by double doors working on parallel swinging-arms

powered by a pneumatic cylinder operated by electro-pneumatic switches. Although the entrances are quite wide, 2ft 8in, at the front and 3ft 11.5in. at the centre, in both cases the actual opening is restricted by the doors which do not open to the full width of the entrance. There is in fact a restriction of 6in. at the front entrance and lft 1.5in. at the centre entrance.

The remaining spaces of 2ft 2in. and 2ft 10in, respectively, comply fully with the legal requirements, I was told. Nevertheless I feel it a shame to restrict boarding and alighting space in this way.

The method of hanging the doors is new to me. A grab rail at each side of the openings is carried in bearings top and bottom. In a compartment above each door the operating ram rotates the grab rails via a pair of cranks. The doors are suspended upon arms clamped to the grab rails top and bottom, and retained parallel to the body by idlers. Rotation of the rails moves the doors out and back on an arc around each grab rail.

Warning lights

Warning lights on the dashboard which come on when a passenger presses what we would refer to as the bell push, stay on until the doors have opened and closed again. These warnings are common on the Continent, but personally I feel that With the

visual senses of drivers already laden to capacity, it is better to make use of a discreet buzzer—and never, please, a bell.

Two problems which have arisen on the most recent tests I have carried out on p.s.v. are screen reflection from interior lighting, and inadequate vision when roads are dirty. In both respects the LVB scores full marks. First, it does not employ curved screens and this makes it fairly easy to avoid the reflection problem. As to screen cleaning, air-powered parallelogram-type wiper arms clear the screen to within lin. of the pillars which themselves are only 1.5in. thick. So even under the worst conditions the biggest blind spot one has to contend with is only 2.5in. wide.

When this screen layout was first designed a mock-up was built and drivers from many different companies were invited to the factory, sat in the mock-up and asked to pass comments about the layout. The result is driving vision under all conditions which can only be described as impeccable. The front end, however, does generate some wind roar at high speeds—and to some tastes may look on the angular side.

The engine of the LVB is slung amidships beneath the floor and it is carried on extremely resilient mountings. A telescopic damper steadies the engine torsionally and at no point on the vehicle is any part of the power unit, transmission or exhaust system joined to the body other than through rubber linkages.

The whole of the flooring is insulated with 1.25in. of glassfibre which, with' the jin. marine plywood-floor covered with linoleum under the seats, and ribbed rubber-matting in the walkways, makes an efficient sound deadener. The level of noise is much lower than in the average British service bus.

A second point in favour of the LVB is that its rubbercushioned road-spring ends transmit little if any road noise into the frame and this also must go towards cutting down the general clamour inside the vehicle.

The test took place in an area within a triangle formed by the cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam and the famous pottery town of Delft. The roads in the area are narrow by our standards, and being devoid of kerbstones fall away at quite steep angles on both sides into the inevitable dyke. Because of my awareness of a false move to the nearside of the road putting the vehicle and occupants in danger of a ducking, and the extremely narrow margin of clearance between passing vehicles—excluding motorways the average width of roads used was 20ft—I grew quickly to appreciate the superb qualities of the ZF power steering. One may be inclined to think that power steering is not necessary on a single-deck bus, but to get one's nearside front wheel off the metalled surface of a Dutch road onto a 45deg bank leading into 10ft of water alters one's opinion very quickly indeed!

Through a misunderstanding on the phone when making arrangements for the test, I arrived to find a vehicle with no test continued overleaf

load, but thanks to the co-operation of the authorities J was able to have a load of 45 Dutch soldiers for an afternoon.

The vehicle's general performance was of a high order. Although the maximum speed was barely 59 mph, and despite road conditions which did not engender fast driving it was possible to keep up quite high average speeds. This was mainly because of the excellent flexibility of the machine. Driving in heavy traffic in strange surroundings and on the "wrong" side of the road was made relatively easy by the simplicity of the controls, particularly the Pneumocyclic transmission.

A 19.7ft wheelbase and overall length of 38.911 could prove to be a distinct problem if the vehicle was in the least skittish or lumbering. The LVB came out well on these points and was far from being the least easily handled bus I have tested despite its being—by nearly 311—the longest and also the heaviest singledecker.

Because of heavy rain, sleet and snow and difficulty in finding a suitable site which would not land me in a dyke if the vehicle deviated from my chosen path during brake tests, I was restricted to some stops from 20 mph using a Tapley meter. The footbrake produced retardation of 0.64g while the single-pull handbrake produced the excellent figure of 35 per cent.

During these tests, torque reaction on the rear axle caused the flexible pipe to the rear-axle brakes to chafe on the prop-shaft coupling flange. At a later stage of the test I gained first-hand knowledge of the efficiency of the split circuits in the braking system for, at the end of the full speed test on the AmsterdamRotterdam motorway, when bringing the vehicle to a fairly smart halt, the offending hose burst leaving me with only front-wheel brakes. Assistant service manager Stanley Smit, who was accompanying me, crawled underneath and located the problem, and as we were some 40 miles from our base at Gouda, I decided to carry on, with caution, with front-wheel brakes only.

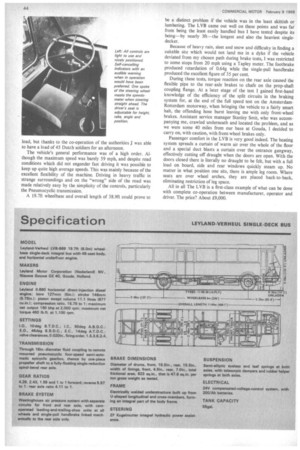

Passenger comfort in the LVB is very good indeed. The heating system spreads a curtain of warm air over the whole of the floor and a special duct blasts a curtain over the entrance gangway, effectively cutting off draught when the doors are open. With the doors closed there is literally no draught to be felt, but with a full load on board, side and rear windows quickly steam up. No matter in what position one sits, there is ample leg room. Where seats are over wheel arches, they are placed back-to-back, eliminating restriction of leg space.

All in all The LVB is a first-class example of what can be done with complete co-operation between manufacturer, operator and driver. The price? About £9,000.