ERF HEADS THE CLASS

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

Page 59

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

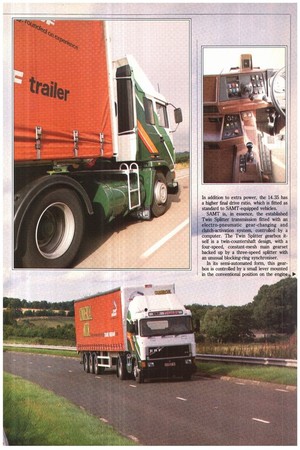

Eaton's SAMTis now in production, and specified on ERF's 14.35. It helped the ERF to return the best combination of performance and economy we have ever recorded on a 38-tonner.

• Eaton's semi-automated mechanical transmission (SAMT) has been widely discussed in recent years. When we conducted a full test of an MAN 16.331 fitted with a prototype SAMT (CM 18 October 1986) we said of it: "The beauty of the Eaton system is that it takes nothing away from the efficiency of the base Twin Splitter gearbox . . . it is a system worth waiting for."

Now SAMT is in production, and ERF is the first manufacturer to specify it as a standard fitment. We were naturally keen to assess the production SAMT, especially in the ERF `E' Series, a range which has impressed us in previous tests.

Our test vehicle is a 14.35, the model designation indicating the presence of the 14-litre Cummins engine in its E350 (246kW installed) form. We have not tested the El4 at this power before; our previous test (CM 10 May, 1986) covered the 225kW-engined version in 6x2 form. In addition to extra power, the 14.35 has a higher final drive ratio, which is fitted as standard to SAMT-equipped vehicles.

SAMT is, in essence, the established Twin Splitter transmission fitted with an electro-pneumatic gear-changing and clutch-activation system, controlled by a computer. The Twin Splitter gearbox itself is a twin-countershaft design, with a four-speed, constant-mesh main gearset backed up by a three-speed splitter with an unusual blocking-ring synchroniser.

In its semi-automated form, this gearbox is controlled by a small lever mounted in the conventional position on the engine cover (unlike the MAN's column-mounted lever) which has simple 'up' and 'down' functions, and a conventional clutch pedal which is used only for starting from rest. Gearchanges are made entirely automatically once signalled: the computer also controls engine speed so that the unit can effectively double-declutch to perform perfectly-synchronised changes.

Skip changes of up to three gears are made by tapping the lever rapidly as many times as gears are required. Where a very large step is required — such as when accelerating away from a roundabout which was approached in top — the driver can wait until engine speed is below 900rpm, whereupon a single down-change tap on the lever will automatically select the appropriate gear.

This intriguing transmission is mounted in an otherwise-conventional powertrain, with the Cummins engine driving a Rockwell axle. The ERF chassis is heavier than it was in the old 'C' Series; metal thickness has been increased from 6mtn to 8mm. The whole tractor unit is still commendably light, however, thanks at least in part to the unusual cab structure, comprising a welded square-tube steel frame clad in sheet-moulding compound (SMC) plastic panels.

The `E' Series tractors are normally powered by Cummins — either the 10litre LTA 10-290 or the older 14-litre units in a variety of states of tune — but Gardner and Perkins (née Rolls Royce) Eagle engines are also available. The Eaton Twin Splitter is the standard 'E' Series gearbox.

• PERFORMANCE

The Cummins NTE 350 turbocharged engine produces its maximum power of 246kW at 1,900rpm, with a maximum torque of 1,595Nm at 1,200rpm. Except for a very few occasions when maximum power was needed to climb the very steepest hills on our test route, we were able to keep the engine speed within a very narrow band.

The ERF 14.35 is one of the quickest 38-tonners we have tested over our 'severe gradient' A' road sections, but surprisingly it cannot match some other 260kW (350hp) tractors over faster 'A' roads and motorways. The fast times on hilly sections must be in part due to the brawn of the 14-litre Cummins engine, but the fast-shifting SAMT certainly helps.

Out on the motorways the ERF may be slightly handicapped by its high overall gearing. At 3.73:1, the drive axle has a faster ratio than the standard 3.91:1 for Twin Splitter-equipped vehicles. With this gearing, the 14.35 engine is spinning at just over 1,400rpm at the motorway speed limit, and will pull strongly down to 80km/h in top before dropping away below maximum torque. This top-gear flexibility is reflected in the ERF's exceptional fuel economy on motorways and 'A' roads — but probably also accounts for the slowerthan-average speeds which it achieved. The flexible engine would also pull quite happily at argund 1,000rpm or 64km/h on the slower 'A' road sections.

• FUEL ECONOMY

In this form the ERF is very economical indeed — of the 38-tonners we have tested only the much less-powerful (and slower) 3828 Iveco Ford Cargo returned better fuel figures. The high gearing obviously helps, at the expense of journey times, but again the SAMT must take a lot of credit, its effortless gearchanging encouraging the use of the right gear at all times. The overall fuel consumption of 38.61k/100km (7.31mpg) makes this the only one of the 260kW-class 4x2 tractors to break the 401it/100km barrier, its closest competitor being the Daf 3600ATi, which managed 40.0 dead.

• GEARCHANGING

This aspect of vehicle behaviour rarely calls for its own section in our tests, but the SAMT demands special attention.

We found no problems in adapting to SAMT control. From a standing start the system allows any of the lowest five ratios to be selected. Third or fourth gives the best start on a level surface; after that we found it best to skip alternate ratios in the bottom part of the box, but to take 10th upwards sequentially. Keeping inside the optimum engine-speed range, this gives a rev drop of 300-400rpm, allowing the engine to be kept close to its maximum torque most of the time on the open road.

The useful feature of being able to use a single lever movement to go right through the box to the correct gear when moving away from a roundabout does have some drawbacks. On many occasions we found that having waited for the engine speed to drop to the all-important 900rpm, the single tap would give a ratio lower than that which we would have chosen. Such is the speed of response of the system, however, that such a situation could be immediately rectified by a further tap on the lever.

This speed of response also comes in handy on sharp changes of gradient. Where caution might dictate a block change down three gears to ensure climbing the rise successfully, two gears could be taken at first in the knowledge that the third could be taken safely as and when it became necessary. This not only helped maintain a fast average speed for the conditions, but also conserved fuel.

Should it be necessary to come to a halt in a high gear, a single flick of the switch while the vehicle is stationary automatically selects third gear, ready to pull away without delay. If neutral is required instead, a further two flicks of the lever are called for.

In slow-moving traffic the temptation to depress the clutch can be great, but should be resisted. Anticipation will take care of most circumstances, so the vehicle can be kept rolling in gear, and the clutch need only be depressed on the rare occasions when the vehicle has to come to a complete halt. The benefits of clutchless gearchanging were nowhere more in evidence than on the very hilly section of the A68 between Rochester and Neville's Cross. On a vehicle fitted with a conventional gearbox the heavy (35kg effort) clutch would be in almost constant use — with SAMT it was used only once.

At one point, on a 14% (1-in-7) gradient where the road surface had been worn smooth, a downchange into third gear led to a partial loss of traction. With the tyres slipping and gripping, and the cab bucking, we were loathe to lift off the throttle and lose forward momentum. Feathering the clutch for a moment reduced the torque at the wheels enough for the vehicle to pull smoothly again. Using the clutch in this manner did not cause any untoward behaviour of the gearchange system.

• BRAKING

On the test track the service brakes pulled the vehicle up straight, producing an average deceleration of 0.43G from 64km/h under maximum application according to the Motometer chart. Only the middle trailer axle locked for most of the stop, but that is one controlled by the Girling Skidchek system. We were unable to check the system at the time, but believe the fault to be a mechanical one on our test trailer.

Parking brake performance was less encouraging. Although the spring brake actuators work on the brakes of both axles, only the front brakes locked on our 20% (1-in-5) test slope. As a result, the vehicle slid backwards down the slope.

The service brakes were assisted on this vehicle by a Jacobs engine brake, an unusual fitment on European engines, but widely available on American-designed engines such as Cummins, Caterpillar, Detroit Diesel and Mack. The lake' brake, which uses hydraulic pressure to alter valve openings, in effect turns the engine into a giant compressor.

In this installation a three-position switch on the dashboard allows the action of the Jake brake to be adjusted to allow for varying road conditions. With the vehicle fully laden, we found that the control had to be set at 'maximum' for worthwhile engine braking to be delivered. In that position it was more effective than a typical exhaust brake, and its use should extend brake lining life considerably. Once the dashboard switch is turned on, the brake is actuated by the driver lifting his foot right off the throttle pedal.

• CAB COMFORT

The ERF plastic-panelled steel-frame cab is now quite an old concept, although the latest SP4 version is only a couple of years old, with squared-up rear quarters and a restyled front grille. The frontcorner air deflectors not only smoothe airflow around the cab, but provide a suitable shroud for the intake of the heating and ventilation system. The rear panel is clear of obstructions, apart from the polyethylene engine air-intake stack which rises above the cab roof.

Although it is shrouded in this position by the roof-top spoiler, ERF says the intake gathers an adequate supply of air from a gap in the lower edge of the spoiler.

The cab suspension incorporates Aeon voided rubber blocks with telescopic dampers at the front and coil springs at the rear. This combination gives a good, level ride, with only extreme provocation making the cab roll more than average. Compared with those on cabs of more recent design the ERF cab steps are narrow, but this causes no problem to a driver, as long as his right foot is placed on the bottom rung to start with. The cab interior is modem and attractive. The current trend to fascias which wrap around the driving compartment is less apparent here than in some cabs, but is sufficient to bring the rocker switches and heater controls to within easy reach, and most of the gauges are easily visible. Only the parking brake lever, now mounted on the fascia, is further away from the driver than it was in the previous cab.

The comprehensive instrumentation includes eight minor gauges which are so mounted that when all is well, all their needles are parallel. In best aircraft practice, this makes it easy to spot any malfunction at a glance.

Above the screen a deep header rail incorporates recessed stowage shelves, which have outer lips to prevent paperwork from spilling out. They could be further improved by having lockable lids. Below the standard single bunk there is ample room for luggage, and large door pockets provide a home for maps and books. The floor wells, which finish flush with the door sills, are covered by thick rubber mats which extend up under the pendant brake and clutch pedals.

The light-coloured herringbone-pattern cloth used on the seats and door trims is pleasing to the eye and looks durable. The standard Isringhausen driver's seat, with all the usual adjustments for height, weight and reach, is now complemented by height and rake adjustment of the steering column.

• SUMMARY

Eaton's SAMT transmission transforms a good vehicle into a very good one: the E14.35 offers the best combination of performance and fuel economy of any 38-tonner we have tested. The computercontrolled transmission, with its dual benefits of reducing driver fatigue and protecting the engine from over-speeding, does an excellent job of gearchanging, and does not seem to harm fuel economy.

Matched to the 14-litre Curiunins engine in this, its first production application, it provides a very-well-balanced driveline, which gives results over our demanding test route that will be difficult to better.

by Bill Brock