BEST GARDNER FUEL ;URES YET

Page 54

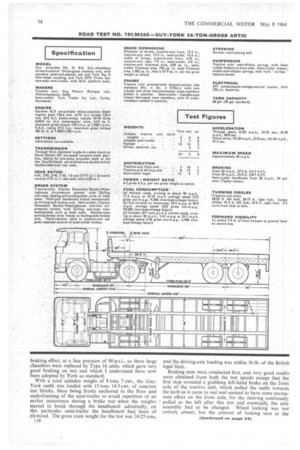

Page 55

Page 56

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

I DON'T know whether it is that Gardner 6LX engines I have gradually been getting better over the years, or whether users of these engines have gradually improved their chassis designs to take better advantage of the LX's characteristics, but whatever the reason successive tests ot 24-ton vehicles with LX engines have been producing better and better fuel-consumption figures. As I have not heard of any modifications having been made to the basic automotive 6LX design, I can only assume that it is the chassis makers who are responsible for this improvement by adopting such features as more efficient transmission lines —bevel instead of worm axles, for instance—and reducing rolling losses.

The first Gardner 6LX engine I tested was in a vehicle which passed through my hands at the end of 1958, and this was a tandem-worm-axle rigid eight-wheeler. Cruising at a mere 30 m.p.h., the best fuel figure obtainable was 8.8 m.p.g. During the next three years it was rare for an LX-engined 24-tonner to exceed 9 m.p.g., but in the past year or so consumption tests at higher cruising speeds have been giving figures of more than 10 m.p.g.

The most recent Gardner 6LX that I have tested was in a Guy Invincible Mk. III tractive unit, and this gave the quite remarkable figure of 11.2 m.p.g when cruising over normal roads at about 40 m.p.h.not only the best figure that I have obtained with a 6LX, but also the best ever achieved during one of this journal's road tests with a 24ton vehicle. So between them Gardner, Guy and York (who made the semi-trailer) have produced a record-breaking vehicle in the fueleconomy sense.

The test outfit was good in other respects also. Highly satisfactory braking figures were obtained— admittedly, after a certain amount of modification to various units—whilst the acceleration and hill-climbing performances were well up to the standard normally obtained with a 6LX pulling this weight. The vehicle handled well also—again after one or two modifications— whilst the latest version of the Guy cab is comfortable and well finished, albeit somewhat noisy. So all in all this turned out to be a most satisfactory vehicle, and if this is typical of current Guy products it is not surprising that this company has managed to re-establish itself so quickly under _Jaguar leadership.

Introduced just before the 1962 London Commercial Motor Show, the Mk. III Invincible tractive unit is based on a design originally produced for British Road Services, differing mainly from its predecessor in having a 9-in.-deep chassis frame instead of 12 in. in order to reduce the fifth-wheelcoupling height, but also incorporating such improvements as a forward-step cab, caminstead of wedge-type brakes, and a David Brown six-speed constant-mesh gearbox. Originally a new type of rearengined mounting was adopted also, this incorporating twin rubber mountings at each side of the bell housing and a raised cross-member passing over the clutch housing and carrying the batteries.

Recently, however, the earlier type of Guy tubular mounting passing through the bell housing has been readopted, with the battery mounting moved to the right side of the frame, above the spare-wheel position. At the time of introduction there, was a price reduction of £140 also, making the Mk. III model £3,330 with the old-type cab and £3,390 with the de-luxe forward-step cab: the price of £3,390 still applies when the "standard alternative" forward-access cab is specified, the price with step-overwheel cab also being unchanged at £3,330.

The Invincible Mk. III 24-ton tractive unit is offered with virtually only one specification, the 6LX engine, David Brown 657/11 overdrive-top gearbox and Guy/Kirkstall double-reduction axle all being standard, the only possible change to the specification being that a final-drive ratio of 7-01 to I can be specified in place of the standard 6.28-to-1 gearing: this js only likely to be necessary when the unit is used at its overseas rating of 32 tons gross train weight. A Kirkstall 4-ton front axle with phosphor-bronze king-pin bushes and hardened steel thrust buttons is standard, whilst the short propeller shaft has Hardy-Spicer 1700 universal joints.

The 3-in.-wide front and rear springs have effective lengths of 52 in. and 48 in. respectively, and Aeon rubber helper springs are incorporated at the front axle. The Girling cam-type brakes are actuated by BendixWestinghouse type diaphragm chambers, controlled by an E valve worked by a conventional brake pedal. A Guy multi-pull handbrake is now employed, this not incorporating controlled release. The Burman recirculating-ball steering is unassisted: recent development work in connection with the column length and type of steering wheel has raised the wheel rim relative to the driving-seat cushion to give increased knee room.

As with the original type of Guy cab, the forward-step model—which is available on Invincible Mk. II and Warrior chassis also—has an all-steel base structure and moulded-plastics superstructure, Although the step ahead of the front wheel is rather small, it is nevertheless very useful and saves a lot of awkward stretching: its height above ground level is just under 2 ft., and there is a grab handle to the side of each door aperture to simplify access. The door opening is wide, but because the doors are so large the provision of check arms to hold them open would be an advantage. Furthermore, because both the hinges of each door are below the waist line, the tops of the doors shake rather a lot, Besides incorporating the easier access layout, the new cab has a better interior finish Than the original version, including the copious use of black trim material on the door panels, engine cowl and seats. The floor area is fully covered with ribbed rubber, and a black crackle finish is applied to certain other interior panels. The instruments and switches are now housed immediately ahead of the steering column, where they are far easier to see and reach, but minor criticisms include the the lack of stowage space for papers and other small items, the awkward location of the window-winding handles, the relatively small area of the windscreen which gets swept by the wipers, and the inadequacy of the heating system. The cab of the vehicle I tested was by no means draught-free either, whilst something will have to be done about noise insulation, for the reverberating boom almost constantly present in the cab hurts the ears and numbs the senses.

The tractive unit had been fitted with a York Big D fifth-wheel coupling, and thus equipped, its kerb weight was exactly 5 tons. The semi-trailer was of the York EP17 type, with 26-ft. platform bodywork and Yolloy Castellabeam main framing members. The semi-trailer had the original type of York "no hop" tandem-axle suspension, with pressed-steel rocker beams linking the rear ends of the springs on each side, and the brakes consisted of Girling heavy-duty cam-operated two-leading-shoe assemblies.

When the semi-trailerwas received at the Guy factory prior to my test, the engineers there discovered that Type 24 (24 sq. in.) brake chambers were fitted, and a quick calculation showed that these would produce twice the desirable

braking effect, at a line pressure of 80 p.s.i., so these large chambers were replaced by Type 16 units, which gave very good braking on test and which I understand have now been adopted by York as standard.

With a total unladen weight of 8 tons 7 cwt., the GuyYork outfit was loaded with 15 tons 14-5 cwt. of concrete test blocks, these being firmly anchored to the floor and underframing of the semi-trailer to avoid repetition of an earlier occurrence during a brake test when the weights started to break through the headboard: admittedly, on this particular semi-trailer the headboard hadbeen of plywood. The gross train weight for the test was 2+25 tons, c18 and the driving-axle loading was within 56 lb. of the British legal limit.

Braking tests were conducted first, and very good results were obtained from both the test speeds except that the first stop revealed a grabbing left-hand brake on the front axle of the tractive unit, which pulled the outfit towards the kerb as it came to rest and seemed to have some permanent effect on the front axle, for the steering continually

• pulled to the left after this test and eventually the axle assembly had to be changed. Wheel locking was not entirely absent, but the amount of locking seen at the semi-trailer wheels was slight, and there were no signs A hop. The efficiency of the semi-trailer brakes by them;elves was indicated by the average Tapley-meter reading A 30 per cent resulting from stops made with the handreaction valve from 20 m.p.h.

By way of interest, Tapley meters had been placed on the chassis frames of both the tractive unit and the semitrailer, and the differences in the figures obtained are worth recording. From 20 m.p.h., the tractive-unit meter gave an average reading of 75 per cent, whilst the meter on the semi-trailer averaged 63 per cent During the stops from 30 m.p.h. the tractive-unit meter averaged 90 per cent, whilst the other meter showed 71 per cent. The meter readings when making the hand-valve stops were identical, but the footbrake discrepancies do show the errors that can arise with this type of equipment because of pitching of a tractive unit as a result of weight transference.

The acceleration results obtained both through the gears and in direct drive were about average for a 24-ton 6LXengined outfit and, as usual, it was impossible to find a long enough stretch of level road on which to take figures up to 40 m.p.h. Engine and transmission smoothness in direct drive from 9 m.p.h. upwards was notable. Checks on the individual gear speeds from bottom to top showed approximate figures of 5, 8-5, 13-5, 21, 32 and 46 m.p.h. Hermitage Hill, Bridgnorth, was the scene of the gradientperformance tests, this ascent having an average severity of 1 in 12 and being 0-75-mile long. A non-stop climb was made in an ambient temperature of 12°C. (54°F.), and the 4-min. 45-sec. ascent caused the temperature in the pressurized cooling system to rise from its normal valueof 57°C. (135°F.) to only 63°C. (146°F.). The lower slopes of the hill were surmounted in second gear at just below governed speed—about 8 m.p.h.—but bottom gear had to be engaged for a total time of 3-5 min., with the road speed at no more than •5 m.p.h. There was no exhaust smoking during this ascent, and the climb, although in no sense fast, was at least as good as can be expected from this class of vehicle.

Good Fade Resistance

Fade-resistance was checked by coasting down Hermitage Hill in neutral, using the footbrake alone to hold the speed down to a maximum of 20 m.p.h. The descent lasted 1 min. 52 sec., and a full-pressure stop at the bottom of the hill made from 20 m.p.h. showed thatsthe maximum efficiency had fallen by only 0-1 g, whilst there was ample braking power to cause slight wheel locking on the wet road surface. This degree of fade resistance is good, and highlights the value of generously proportioned brakes. As an experiment, I also made a trial descent in bottom gear to See if I could get away without using the footbrake at all, but this was not possible as on several occasions the engine went past its normal governed speed. The steepest part of Hermitage Hill has a gradient of 1 in 7.5, and the Guy-York was stopped on this slope facing up hill. The tractive-unit handbrake alone just held the outfit, and in the same way a hard pull on the semitrailer parking brake prevented backward movement also. Application of the semi-trailer brakes_ by means of the hand-reaction valve held the outfit very easily, and following these brake tests a smooth bottom-gear restart was carried out after clutch slip had prevented the success of a rather optimistic attempt at starting in second gear. The power of the three individual brakes was shown to be about the same facing down this 1-in-7-5 slope as when facing up it, whilst a reverse restart was made quite easily.

So much performance did the Guy appear to have in hand on this slope that I then drove it to Old Hill, Tettenhall Wood, where the maximum gradient is 1 in 5. Facing up this slope the separate semi-trailer brakes were again powerful enough to hold the outfit, but the tractive-unit brake would only take effect after being helped on by the footbrake. A bottom-gear restart was then made quite easily.

Facing down the hill the semi-trailer brakes held when applied by the hand reaction valve, but the parking brake would not hold because • the lever acts on the leading axle brakes only, and the wheels locked and slid on the slope. Again the tractive unit handbrake had to be helped on by the footbrake, but once on it was just powerful enough to hold the outfit. Clutch slip almost prevented a reverse restart, but the vehicle was finally got under way after a bit of a struggle. These gradientperformance tests were most impressive, and show the Invincible Mk. III tractive unit to be able to cope with virtually any slope likely to be met in normal service. The normal-road laden and unladen fuel runs were made over a 16-35-mile out-and-return circuit using the Wolverhampton-Stafford road as far as Gailey, and then turning south along AS as far as the Cannock roundabout. Where conditions permitted the vehicle was cruised at 40 m.p.h., and both sets of figures obtained are very satisfactory, the laden result—as already explained—setting up a new record for a vehicle of this weight. The full-throttle motorway run was made over a 31-mile return stretch of M6 between Dunstan and Stafford, and again a very good fuel figure was obtained, whilst the average speed was quite high in view of the fact that gradients caused the speed to drop to as low as 21 m.p.h. on some sections.

Once fitted with a new axle to replace the one affected by the brake tests, the Guy-York outfit handled well, although the steering was a little on the heavy side considering that the front-axle loading was under 4 tons. The steering gear itself is highly efficient, so the fault lay either with the axle or the Michelin " X " tyres. For a shortwheelbase tractive unit the ride was quite good, but semitrailer tugging was pronounced at times, and on certain occasions it felt almost as if the coupling had play in it. Tractive-unit pitching was present, but I can think of quite a few British units that suffer from this to a far greater degree. The brakes were good at all times, although the pedal was a little too sensitive.

The engine pulled like a Gardner—I think that says all that.needs to be said—and if only its noise could be kept down a bit, life would be a lot more pleasant for a driver of this vehicle. The gearchange was virtually faultless, whilst the clutch was light to operate and smooth in action. In the dry the general range of vision was entirely adequate (my comments regarding the wiper sweeps have already been made), and the large external sun visor really does keep the sun out of the cab.

These are relatively minor points, however, and taking things generally I have nothing but praise for this GuyYork combination when running at the British legal limit of 24 tons. It is well built, so maintenance costs should be low, whilst fuel costs cannot help but be at a minimum for this class of vehicle. Furthermore, the de luxe cab provides just about as good driving conditions as any other current British heavy. With a tractive-unit price of 0,390, and a list price of £1,614 for the York EP17 26-ft. semitrailer (complete with headboard), the complete outfit comes out at £5,004. Not a bad investment at an.