DIFFICULTIES of CLASSIFYING GOODS for ROAD TRANSPORT A Logical Method

Page 30

Page 31

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

of Reducing the Number of Classes to a Minimum but Still Retaining the Disadvantage that All Goods Must be Listed and Placed in Their Classes

Solving the Problems of the Carrier

BY a process of elimination described in last week's article, I have reduced the conditions governing the classification of goods for transport by road to the following—time needed to load and unload; value; liability to cause damage to the vehicle.

At first sight it seems that these three conditions still involve a considerable number of classes, for each is independent of the others, yet each may involve either or both . of the others. That is not very clear. Let us examine the problem in detail, and classification will follow.

Take the factor of loading and unloading time. It should be sufficient to provide for three classes under this heading: 1, goods which take a normal time to load and unload; 2, goods which take half as long again for those combined processes: 3, those which take twice as long. Time spent at terminals in excess of mat provided for in the third class should be charged for at demurrage rates.

Turning now to value, here again, there might be three classes: 1, goods of sub-normal value; 2, goods of normal value; 3, goods of value greater than normal. Now, clearly, each of these three may be subdivided according to the time needed to load and unload the goods included in each class, so that from consideration of those two factors alone have arisen nine classes.

If we go farther and accept the proposition that there may be three. classes according to damage which is liable to accrue to the vehicle, namely, one class for normal goods, one for goods which do a small amount of damage, and one for goods which are liable to cause severe damage, we can easily justify 22 classes in all, which is absurd.

Consolidating the Classes to Reduce Their Numbers These three factors should, however, be taken into consideration. The question is, can the above 27 classes be consolidated to give us the effect we want, with a reduction in numbers? I think they can.

First, it will readily be acknowledged that the bulk of goods carried by road fall into the normal category in respect of all the above three main considerations—they take a normal time to load and unload, are of normal value, and do not cause undue damage to " the vehicle. These constitute our main classes, to • which any others mast, to a certain extent, be-subsidiary.

The primary factor which must be taken into consideration is that of loading and unloading time. This consideration will involve the formation of two classes besides ' the first: one comprising goods which take half as long again to load and unload as do those included in the " normal" class, and another of goods which need twice that period of time for loading and unloading. Let these classes be referred to as L1, L2, 1.3. .

Now, consider the factor Of value. Goods which are normal in this respect will be in the main class already described. There will also, presumably, be a class for goods which are subnormal, being of so low a value that hauliers, if they desire to carry them, must make concessions in regard to the rates they charge. Correspondingly, there must be a class of goods the value of which is above normal. Now, each of these may take the normal time to unload, thus coming under Ll, for that condition, or may take half as long again, coming into Class L2, or double time, coming into Class L3.

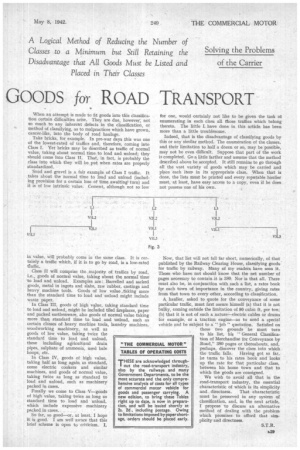

If the value classes be designated V1, V2, and V3, then, altbgether, there must be nine classes—V1L1, V1L2, V11,11, V2L1, V2L2, V2L3, V3L1, V3L2, V3L3. How this comes about is illustrated diagrammatically in Fig. 1.

When, however these classes come to be rated, it may well be that Class V1L2, the low-valued goods in the second class according to loading and unloading times, may be charged at a rate differing little, if any, from V2L1. Similarly with some of the others, so that in point of actual rating, the relation between the classes is better shown by Fig. 2. If that he so, it will almost certainly be found practicable to merge them, as shown in Fig. 3. In that event it will be practicable to compress the nine to five.

A Factor That Can with Perfect Safety Be Ignored

I am going to suggest that the third factor, damage to vehicle, is one that can be ignored. I am not going. to be persuaded that, except in unusual circumstances, for which exceptional rates may be quoted, the damage involved is going to add one farthing per mile to the cost of operating a 10-ton vehicle. Now one farthing per mile over a 200mile route is 50d., or 5d. per ton. No rate has ever been fixed, or can be calculated, with such accuracy that 5d. per ton over a journey from Manchester to London is going to be worth serious consideration, as a basis for classification. It cannot be done.

It does seem, therefore, that goods for transport by road can be compromised within five main classes (I have not overlooked the problem of bulky traffics; I dealt with them in the previous article).

These classes are :*—(i) Goods of low value„ taking the normal time to load and unload. (ii) Normal goods, taking normal or standard time to load and unload; goods of low value taking up to half as long again as the standard time for loading and unloading. (iii) Goods of high value, taking standard time to load and unload; goods of normal value, taking half as long again as standard time to load and unload; goods of low value, taking twice the normal time to load and unload. (iv) Goods of high value, taking half as long again as standard; goods of normal value, taking twice as long as standard. (v) Goods of high value, taking twice the standard time to load and unload. When an attempt is made to fit goods into this classification certain difficulties arise. They are due, however; not so much to any inherent defects in the classification, or method of classifying, as to malpractices which have grown, cancer-like, into the body of road haulage.

Take bricks, for example. In pre-war days this was one of the lowest-rated of traffics and, therefore, coming into Class I. Yet bricks may be described as traffic of normal value, taking about normal time to load and unload; they should come into Class II. That, in fact, is probably the class into which they will be put when rates are properly standardized.

Sand and gravel is a fair example of Class I traffic. It takes about the normal time to load and unload (including provision for a certain loss of time awaiting turn) and it is of low intrinsic value. Cement, although not so low in value, will probably come in the same class. It is certainly a traffic which, if it is to go by road, is a low-rated eraffic.

Class II will comprise the majority of traffics by road, i.e., goods of normal value, taking about the normal time to load and unload. Examples are: Barrelled and sacked goods, metal in ingots and slabs, raw rubber, castings and heavy machine tools. Goods of low value _taking more than the standard time to load and unload might include waste paper.

In Class IV, goods of high value, taking half as long again as standard, come electric cookers and similar machines, and goods of normal value, taking twice as long as standard to load and unload, such as machinery packed in cases.

Finally we come to Class V—goods of high value, taking twice as long as standard time to load and unload, which include expensive machinery packed in cases.

So far, so good—or, at least, I hope it is good. I am well aware that this brief scheme is open to criticism. I, for one, would certainly not like to be given the task of enumerating in each class all those traffics which belong thereto. The little I. have done in this article has been more than a little troublesome.

Indeed, that is the disadvantage of classifying goods by this or any similar method. The enumeration of the classes, and their limitation to half a dozen or so, may be possible, may not be even difficult. Suppose that part of the work is completed. Go a little farther and assume that the method described above be accepted. It still remains to go through all the vast variety of goods which may be carried and place each item in its appropriate class. When that is done, the lists must be printed and every reputable haulier must, at least, have easy access to a copy, even if he does not possess one of his own.

Now, that list will not fall far short, numerically, of that published by the Railway Clearing House, classifying goods for traffic by railway. Many of my readers have seen it. Those who have not should know that the net number of pages necessary to contain it is 380. Nor is that all. There must also be, in conjunction with such a list, a rates book for each town of importance in the country, giving rates from that town to every other, according to classification.

A haulier, asked to quote for the conveyance cd some particular traffic, must first assure himself (a) that it is not bulky, coming outside the limitation of 80 cubic ft. per ton; (b) that it is not of such a nature—electric cables or drums for example, or a traction engine—as to need a special vehicle and be subject to a "job " quotation. Satisfied on • these two grounds he must turn to his list, his " General Classification of Merchandise for Conveyance by Road," 380 pages or thereabouts, and, perhaps, discover the class into which the traffic falls. Having got so far, he turns to his rates book and looks up the rate for that particular class, between his home town and that to which the goods are consigned.

We wish to avoid all that in the road-transport industry, the essential characteristic of which is its simplicity and, directness. That characteristic must be preserved in any system of classification, and, in the next article, I propose to discuss an alternative method of dealing with the problem which promises to afford that simplicity and directness.