The Railway Road Transport Bills.

Page 69

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

AT the second day's sitting of the Joint Select Committee on the Railway Road Transport Bills, Mr. H. P. MacMillan, K.C., concluded his opening speech for the promoters. In our last issue we summarized the proceedings of the first day. Mr.MacMillan laid some emphasis on the statement that the question of allowing railways to go on the roads had already been before Parliament, and sporadic powers had been given to the railway companies. The Furness Railway, for instance, had power to use coaches and other vehicles in connection with services in the Lake District. The North Staffs Co. had similar power.

The G.W.R. Passenger Services.

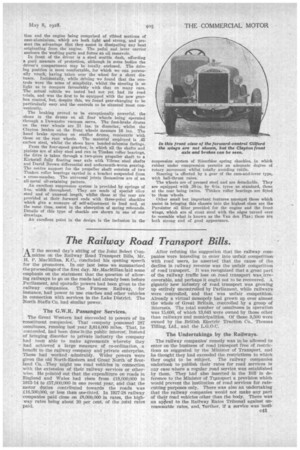

The Great Western had succeeded to powers of its tonstituent companies. That company possessed 287 omnibuses, running last year 3,814,000 miles. That, he contended, had been done in the public interest. Instead of bringing disorder to private industry the company had been able to make agreements whereby they had achieved a large measure of co-ordination, a benefit to the railway company and private enterprise. These had worked admirably. Wider powers were given the old North-Eastern and Great North of Scotland Co. They might use road vehicles in connection with the extension of their railway services or otherwise. He pointed out that the expenditure on roads in England and Wales had risen from £18,000,000 in 1913-14 to £57,000,000 in one recent year, and that the motor duties contributed towards the roads was £16,500,000, or less than one-third. In 1927-28 railway companies paid close on £8,000,000 in rates, the highway rates being about 20 per cent, of the total rates paid. After refuting the suggestion that the railway companies were intending to enter into unfair competition with road users, he asserted that the cause of the decline in railway revenue was the unfair competition of road transport. It was recognized that a great part of the, railway traffic loss on road transport was,irrecoverable, and perhaps it ought not to be recovered. A gigantic new industry of road transport was growing up entirely uncontrolled by Parliament, while railways were controlled, and that was unfair competition. Already a virtual monopoly had grown up over almost the whole of Great Britain, controlled by a group of interests. The total number of omnibuses in operation was 15,600, of which 13,643 were owned by those other than railways and municipalities. Of those. 9,500 were owned by the British Electric Traction Co., Thomas Tilling, Ltd., and the L.G.O.C.

The Undertakings by the Railways.

The railway companies' remedy was to, be allowed to enter on the business of road transport free of restrictions as suggested by the Minister of Transport, and he thought they had exceeded the restrictions to which they ought to be subject. The railway companies undertook to publish their rates for road services in any case where a regular road service was established by them. They had also inserted in the Bill in deference to the Minister of Transport a provision which would prevent the institution of road services for ratecutting purposes only. There was also an undertaking that the railway companies would not make any part of their road vehicles other than the body. There was an ate3ea1 to the Railway Rates Tribunal against unreasonable rates, and, 'further, if a service was insti

tilted it could not be stopped without due justification. If that was not subjecting the companies to control and scrutiny he did not know what ft was.

Clause 6 was a sincere effort to bring these into line with public policy. It provided powers to enter into working agreements and arrangements with local authorities and road undertakings. If the opponents had their Way the railways would die of inanition by being deprived of their traffic. They could never be monopolists of road transport, because, to a very large extent, motor vehicles on the road were owned by private individuals and traders.

L.M. and S. Railway Chairman.

Sir Josiah Stamp, chairman of the L.M. and S. Railway Co., who was the first witness for the promoters, maintained that the standard revenue of railway companies tended to be jeopardized by the competition of road transport and an increasing handicap was Inevitable, although they were at the same time faced with demands for increased facilities and reduction ot rates. He dealt with the suggestion that railway companies were so financially predominant that they could • drive competitors off the roads. Out of a total capitalization of .£450,000,000 the L.M. and 8.11 Co. had probably some i3,000,000 which would fall under the head of sums which could be used in this way. But it could see purely railway projects for which such an amount would be required. Only a modest figure would be available for the new services.

The resources of competing transport undertakings were larger than those which railway companies could devote to road transport in association with their other liabilities. The problem of the railway companies was almogt entirely one of co-ordination and they desired to get the best out of both forms of transport. The company had not yet a cut-and-dried scheme ready, but would explore the problem by experiment and extension along most favourable lines. The new powers would enable a better system to be developed and would co-ordinate road and railway services for the public convenience.

An Unpalatable Suggestion.

4 Sir Lynden Macassey, K.C., for the Commercial Motor Users' Association, in cross-examining the witness, suggested that there was nothing in the Bill to prevent the railway company running road services below cost. Witness replied that there was nothing of this kind in the Bill, but as a matter of policy to run road services at a loss would make it difficult for the railway company to attain the standard revenue, and it might lead to an increase of charges on other traffic, which would be an unpalatable suggestion. He admitted that the L.M. and S.R. Co. had not to his knowledge made any proposals of any kind to road trans port interests to co-operate with the railways. The suggestion had not been made that the former would not co-operate with the railways.

Counsel: Have you reason to think that the Commercial Motor Users' Association would not co-operate with you if you asked them?

Witness : In the future, no. I do not know about the past.

He disagreed with counsel's suggestion that the railway company was afraid that the road transport interests would co-operate and that was why the railway companies did not ask them. s, Transport Employers' Federation Conditions.

Cross-examined by Mr. Tyldesley Jones, K.C., who appeared for the National Road Transport Employers' Federation, the witness said that the members of the Federation paid their men on a scale higher than the railways for a 48-hour week, but he pointed to certain superannuation and other benefits which the railway Workers received. He admitted that competition between road and rail was a very strong factor in the promotion of the Bill, but, he added, the invention of the new form of transport was a thing of which the railway companies would want to avail themselves. Counsel sUggestel that the companies had not made proposals to Parliament until tht competition had arrived.

Witness replied that, during the war 'and for gome time afterwards, the railways were out a the hands of the companies. In 1922 they made application to Parliament for road transport powers. Asked whether the railway companies' road vehicles would not intensify competition with the railways he observed that it was the way in which vehicles were used in relation to the railways that mattered.

He indicated that the railway companies wished to make arrangements with other.road users for the public convenience in such matters as timing of trains and sharing the proceeds, whilst a quid pro quo could be given to road users who changed their routes and their methods by the railways providing them with services of various kinds. One reason why these things were not done to-day was that the companies' poWers were limited and they had nothing with which to negotiate. Counsel suggested that the railways wanted to negotiate with a bludgeon behind their backs, but this the witness denied.

Mr. McMillan, counsel for the promoters, interposed with the remark that the railways desired to negotiate on equality of terms which did not now exist.

On Wednesday last Sir Josiah Stamp was still in the witness chair under cross-examination. Mr. J. G. Hurst, K.C., appearing on behalf of the Furniture Warehousemen and Removals Association, obtained from the witness a statement that the L.M. and S. Railway Co. had no intention of going into the business of pacliing furniture or of using their warehouses for the storage a it. All they intended to do was to carry the furniture from one point to another.

In reply to Sir Lynden Macassey, K.C., representing the London General Omnibus Co. and associated interests, Sir Josiah stated that the company had no desire to run large, numbers of omnibuses in the central area of London, He could riot bind himself for all time, but at present they had no inclination to, run competing road services there.

Experimental Services.

The witness was also cross-examined by Mr. Craig Henderson, K.C., on behalf of the Tramways and Light Railways Association. Counsel questioned him as to what was meant by "experimental services" in the Bill. The witness said it meant services which they believed prima facie would pay for themselves and were worth risking money upon to test them out. He admitted such services might have to be rap at a loss.

Counsel asked whether it would not be possible under the guise of running experimental services to run competitors off the road. The witness replied that it was intended to run experimental services as pioneer services. He could not agree that they might he used to destroy competition.

Counsel pointed out that the experimental service was the only one over which it was proposed the Minister of Transport should have no control and the companies might establish experimental services all over the country. Sir Josiah said those experiments would be determined by such things as seasonal fluetuation.s in traffic in the districts concerned.

He was asked who would determine when a service ceased to be experimental and replied that it would be decided by the directors of the company.

Mr. Evan Charteris, K.C., cross-examining for a variety of local authorities, asked whether, if the railways established services in competition with services

• run by municipalities into outside county areas, the railways would be prepared to pay the cost of putting the roads right in the same way as the municipal services. Witness said that that was a matter of adjustment of rates as between municipal ratepayers and county ratepayers. In his opinion the railways did not come under such an arrangement. American Tractor Exports.

The Editor, THE COMMERCIAL MOTOR.

[2679] Sir,—I am very sorry to see America is getting the tractor business of the world, but the fact remains that llenry Ford seems to be the only man who has real confidence in the future of the tractor and possibly the only one with the money to back his belief.

The bulk of all farming cultivation will be done with tractors in the future—that is an absolute certainty as soon as drivers grow up Or are trained to do the work. The only thing which makes tractors expensive in use is bad driving. With good drivers, equine power cannot stand alongside tractors in general use, and I say this after experience -with a number of different makes of tractor on my farms—Yours faithfully,

Thames Ditton. S. F. EDGE.

Satisfaction from Six-wheelers.

The Editor, THE COMMERCIAL MOTOR.

[2680] Sir,—Following on the previous correspondence on this subject, which you published in the two previous issues of The Commercial Motor, a number of incorrect and misleading ideas are being cultivated, for obvious reasons, amongst potential users.

In many cases, where people have not had experience with six-wheeled vehicles, they are frequently under a misapprehension, inasmuch as they think that a six-wheeled vehicle necessitates two additional tyros compared with a four-wheeled vehicle, but this is not the case and we may give, in confirmation of this statement, the following comparisons of 50-seater to 56-seater double-deck buses, or 4-ton to 5-ton lorries, four and six-wheelers:—

• Four-wheeled double-deck bus, or 4-ton to 5-ton lorry.—The load carried on the back axle, smile 5% tons, necessitates twin 7-in. tyres on each of the driving wheels and the front wheels are fitted with single tyres. The vehicle is therefore fitted with six 7-in. tyres.

Six-wheeled double-deck bus, or 4-ton to 5-ton lorry. —As the rear load of some 51 tons is divided between two back axles the load per axle is only some 21 tons, therefore on each of the four driving wheels single 7-in, tyres are fitted; single tyres are also fitted to the front wheels. The vehicle therefore is equipped with six 7-in. tyres.

Incidentally, on four-wheeled vehicles, where the axle loads are in the region of Si tons, necessitating the fitting of twin tyres of about 7-in, or 8-in. section, there arise serious disadvantages, to which, 1 observe, reference was made in the editorial columns of your issue for May 1st : First, to allow for the bulge of the tyres, it is necessary to have about 1-in, clearance, which means that the centre distances of the twin tyres are 8 ins. or 9 ins., and it is found on a heavily cambered road that the inner tyre is taking the majority of the load and because of its reduced diameter compared with the outer tyre a certain amount of scrubbing action takes place, both factors causing excessive wear.

Secondly, where these large twin tyres are fitted the brake drum is entirely hidden by the inner tyre; in consequence, excessive heating takes place, reducing the life of the brake, and this heat is transmitted to the wheel rim and inner tyre, causing more rapid deterioration of the tyre.

In consequence of all this, we understand that the maximum average mileage of twin tyres on a double' c43 deck bus of a capacity of some 50 seats to 56 seats is only some 15,000 miles to 20,000 miles, rthereas on sixwheeled Guy vehicles, using the same size of .tyres, 28,000 miles to 40,000 miles are being obtained.

To support our claim that six-wheeled vehicles give a better mileage and a better petrol consumption on a ton-mileage basis compared with four-wheeled vehicles, operating under similar conditions, because of the reduction in wheelapin that occurs on the driving wheels, the result of some tests recently carried out may be cited.

Two vehicles were tested—a four-wheeler and a six-wheeler, with the same sized engine and similar tyres, and the load carried was so arranged that the weight on each driving wheel of both vehicles was the same. These vehicles were driven up a hill some 250 yards long, with a gradient varying from approximately 1 in 11 to 1 in 8. The number of revolutions of the steering wheels (which, it was assumed, were not subject to wheelspin) were recorded and compared with the revolutions of the driving wheels. The tests were carried out on the same part of the hill, within a few minutes of one another, and no variation occurred in the surface between the tests. In short, the conditions were identical. The result of these tests showed that the driving wheels of the .four-wheeled vehicle slipped four turn8 in 250 yards, whilst the driving wheels of the six-wheeled vehicle slipped one-and-a-half turns. Just think what a difference this is going to make to tyre and road wear and to petrol consumption, with the average bus doing some 40,000 miles per annum!

It might be interesting to have the following facts In connection with Guy six-wheeled vehicles :— (a) Some Guy six-wheelers have each done nearly 100,000 miles and the total mileage of Guy six-wheelers to date is approximately 5,000,000.

(b) Guy Motors, Ltd., has at the time of writing 400 to 500 vehicles on order, of which some 160 are of the six-wheeled type.

(c) As repeat orders prove satisfaction, the following list of both goods and passenger-type six-wheelers will be of interest :—Sixth repeat order from Wolverhampton Corporation, fourth repeat order from Oldham Corporation, fourth repeat order from War Office, third repeat order from London Public Oranibus Co., third repeat order from Leicester Corporation, third repeat order from Hastings Tramway Co., third repeat order from India Office, third repeat order from Burmah Oil Co., second repeat order from Leeds Corporation, second repeat order from Morecambe Corporation, second repeat order from Reading Corporation, second repeat order from Rio de Janeiro Tramway Co., second repeat order from Venezuela Oil Fields, second repeat order from Messrs. J. Lucas, Ltd., second repeat order from Messrs. Chiver and Sons, Ltd., and many others, any of whom would no doubt be pleased to recount their experience on sixwheeled vehicles.—Yours faithfully,

For Guy MOTORS, LTD.,. SYDNEY S. Guy, Managing Director. Wolverhampton.

The Unfair Petrol Tax.

The Editor, THE COMMERCIAL MOTOR.

[26811 Sir,—During the past few days many letters have been written to the newspapers approving the principle of the extra petrol tax, but practically none protesting against the unfairness of putting this extra tax on commercial vehicles. The daily newspapers have given their blessing to the tax and it looks as though they will not publish letters expressing a contrary view. I have written to four papers, but none has published my letter.

Most people are in favour of giving help to such of the producing industries as require it, but why should the bulk of the cost fall on the owners of commercial vehicles, irrespective of the profits they make? After four years of very hard work I have built up a small business which depends on mechanical road transport. I shall now have to pay an, extra £100 per year to help producing industries, and this will mean that I shall pay more in direct and indirect taxes and rates than my net income. A stockbroker or banker with fifty times my income will pay nothing extra.

I am still hoping that somebody will bring the following points to public-notice :

(a) Taxation, to be fair, should be levied on luxuries or spread over all those able to pay. In this case the bulk of extra taxation is to be paid by a comparatively small class, i.e., the owners of commercial vehicles. A fairer but, of course, more unpopular way would be to increase the income tax and make everybody pay according to his capacity.

(b) We are to help the railways because they pay rates. It seems to be forgotten that owners of commercial vehicles also pay. rates.

(c) We must not grumble about the petrol tax because the amount of tax only represents the amount that petrol has recently fallen in price. In other words, if the market favours us the Chancellor is to take the benefit ; if it favours any other trade, that trade is to keep the benefit. It would be just as fair to tax all horses at £1 per head because the price of fodder falls, or tax our shirts when cotton is cheaper. I cannot imagine the Chancellor giving us a grant when petrol again gets dearer.—Yours faithfully, C. G. JOHNSON.

London, N.10.