DOCTOR AT THE ROADSIDE

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by lain Sherriff, MITA

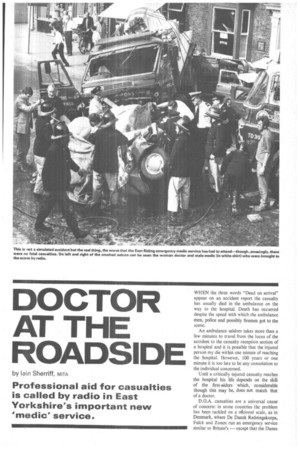

WHEN the three words "Dead on arrival" appear on an accident report the casualty has usually died in the ambulance on the way to the hospital. Death has occurred despite the speed with which the ambulance men, police and possibly firemen got to the scene.

An ambulance seldom takes more than a few minutes to travel from the locus of the accident to the casualty reception section of a hospital and it is possible that the injured person my die within one minute of reaching the hospital. However, 100 years or one minute it is too late to be any consolation to the individual concerned.

Until a critically injured casualty reaches the hospital his life depends on the skill of the first-alders which, considerable though this may be, does not match that of a doctor.

D.O.A. casualties are a universal cause of concern: in some countries the problem has been tackled on a Ational scale, as in Denmark, where De Dansk Redningskorps, Falck and Zonen run an emergency service similar to Britain's — except that the Danes take the doctor to the casualty (CM June 2, 1967).

Television viewers in this country are probably familiar with the State emergency set-up in America where the houseman from the accident hospital travels in the ambulance. In the United States, as in Denmark, the patient pays for this service.

It may seem strange that in Britain where there is so much. concern with national health and a national emergency service exists, we are still taking the casualty to the doctor.

In only one part of the UK, to my knowledge, is there a full-scale comprehensive accident emergency service. Should I ever be involved in a serious road accident, I hope it's in the 1150 square miles of the East Riding of Yorkshire county area. It has a‘service which is geared to put a doctor in attendance at any type of accident within a few minutes of the report. The Yorkshire, East Riding Voluntary Action and Emergency Service (YERVAES) caters for every type of accident, whether on the road, in the workshop, factory, farm or home. It is an extension of a smaller scheme in the North Riding, where accidents on the road are attended by doctors.

The area covered by the East Riding scheme excludes the cities of Kingston and York. It has two trunk roads: A63 and A1079 which feed the 200 acres of dockland in Hull. In the 'summer season its roads carry thousands of vehicles to one of the most popular coastlines in the country.

However, generally traffic in the region —a rural area—is not exceptionally heavy; in fact the East Riding is a pretty average sort of place—except in its approach to accidents.

Basically, the system in the East Riding differs little from those other places in that after an accident the first action to be taken is to contact the emergency service in the usual way. Dial 999, then request calmly and clearly the service or services required and answer other relevant questions which the telephone operator may put. If an ambulance is specified the telephonist will contact ambulance control at Beverley where the controlling officer will direct one of his vehicles to the scene by radio control, while putting out a call for one of the twenty doctors on a panel of volunteers in the area to go to the scene of the accident. This is the big difference between the East Riding and most other places. They take the doctor to the patient and reduce the D.O.A. risk.

Simple solution

The scheme began in 1969 when members of the medical profession together with representatives of the ambulance, fire and police services met to discuss a new way to tackle injuries resulting from road accidents. The main problem facing the meeting was how to avoid delay in getting medical assistance to the patient. As with so many problems the answer was so apparent that it could not at first be seen: they could take the doctors to the casualties.

A study of accident procedures indicated that casualties involved in road accidents were liable to sustain further injuries, while they were being extricated from the damaged vehicle and transported to hospital. The desire for speed and an understandable sense of urgency frequently took priority and the casualty was rushed to a hospital having received, in many cases, only basic first-aid treatment when in fact skilled medical attention was vital—not least in extricating casualties from vehicles without causing further injury. A pilot scheme was launched to measure the value of having doctors constantly available. Four doctors from the more isolated sections of the East Riding had two-way radio control sets fitted to their own cars by the county council: their call signs were Medic 1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively. The results of the scheme were modestly expressed by the scheme's patron, the Earl of Halifax, as "most encouraging". In fact what became immediately apparent was that often the general practitioner arrived at the scene of the accident before the regular emergency services.

Having looked at the operation from the sidelines for a few months, other doctors in the area saw much merit in it and volunteered their services. So important has it become in the eyes of the county's 250,000 population that those doctors who still have some doubts find themselves in an embarrassing situation when confronted by a patient who asks: "Are you in the emergency service?"

Gradually, it has expanded and there are now 20 doctors operating the scheme, and there is little doubt that it is a success. That it should continue to succeed, I was told, depends on a number of factors. It is vital that there should be a sufficient number of GPs willing to co-operate. While the initial response may have been slow, the indications now are that supply will soon outstrip demand.

GPs who participate not only give their services free but make no charge for the use of their cars. Dr J. R. Brown, the committee chairman, told me that the only allowance they received was for the cleaning of soiled suits.

Those GPs who volunteer their services must be prepared to spend spare time, a commodity which they find in short supply, to take a course to develop expert knowledge of rescue and life-saving techniques. This helps in an appreciation of the part played by the other three services. For example, the GPs must understand when it is safe or necessary to cut away cab pillars or pull out dented panels. When an accident occurs, those attending decide quickly on a plan of action at an on-the-spot meeting and then they get on with their own allocated tasks. No one takes overall charge.

Finance is another important factor in the scheme's success. Although the local authority supplies the equipment, it has to be paid for by the emergency service. None of the costs can be financed from public funds and the service depends upon voluntary subscriptions—if necessary, I understand, from the pockets of the volunteers themselves. To equip a car with the control set and the necessary emergency kit, which is carried at all times, costs about £200 with annual running costs amounting to some £50.

National organizations with local branches or divisions, such as the Road Haulage Association, Round Table, Lions, Association of Industrial Road Safety Officers and British Petroleum Ltd have all contributed, as well as a number of local firms. The scheme has been registered as a charity with the Charity Commissioners and covenant forms have been taken up by local people who wish to contribute.

The 20 GPs who are now equipped with rkiclio control can be contacted by radio all the time they are in their cars. But they are available at all times because they always leave telephone numbers or other means of contact when they go off the air.

This is an excellent scheme, and I saw it in operation when I visited the East Riding recently. I spent the Friday evening, Saturday and Sunday with the committee chairman. During that time four calls came for medics and each time within five minutes of the call going out the doctor was reporting his or her arrival at the scene of the accident.

I accompanied Dr Brown to one call—to the A1079—within seconds of the report. However, despite our very fast run another medic, who had been closer at hand, had attended, treated the patient, dispatched him to the hospital by ambulance and reported his condition to the hospital via the ambulance service over his car radio before our arrival. Another call I heard resulted in the doctor being able to turn the ambulance round because he had ascertained that the patient did not need hospital attention.

Two accidents have particularly revealed the real value of the scheme. On October 26 on an isolated road two heavy goods vehicles met almost head on. Within minutes of the emergency call going out, a doctor was in attendance and although the drivers had sustained injuries they benefited greatly from receiving such prompt attention.

Attic accident

Last August provided the most demanding call in the life of the service, when in Market Weighton, at the bottom of a steep hill on the busy Hull to York road, There was a multiple accident involving 11 vehicles. A 32-ton artic ended up with its front wheels on top of a Hillman Minx saloon in which were trapped two women with severe injuries.

There were two casualties on the pavement, one a man with a spinal injury and the other a boy with head and chest injuries. Another passenger from the Hillman Minx who had managed to free himself was suffering from shock. The two lorry drivers were suffering from minor cuts and abrasions and shock.

It took 1 hour 50 minutes after the first call to complete the entire operation of attending to the casualties, removing them to hospital, clearing the damaged vehicles and re-opening the road to traffic.

Two doctors, four ambulances, and three cars were used in the treatment and transportation of the casualties. In his report on the incident Mr Frederick Thornley, the assistant ambulance officer, said: "It is my view that an accident of this nature proves conclusively that speed is not necessarily the overriding factor in the treatment of casualties."

When I queried his with Mr Thornley, he assured me that he was referring to speed of removal to hospital. "Speed in arrival at the site is an entirely different thing," he said. Just how useful is the voluntary scheme was illustrated by Mr Thornley: "The severing of a major artery can result in death in four minutes; if it takes eight minutes to get to the casualty and get him to the hospital he is four minutes dead on arrival."

On Wednesday, January 28, 1470 the A63 Hull-to-Howden road had a covering of black ice and during the period between 9 am and 5 pm, medic 1 attended 15 accidents. In only two cases did he require the services of an ambulance. In those two occasions the goods vehicle drivers were seriously injured and trapped in their vehicles. Therefore in addition to Calling for the ambulance the doctor also called for the fire brigade.

On the Friday of my visit I travelled 17 miles alone the Hull-Howden road and counted 250 commercial vehicles and coaches in 25 minutes. I have since made random checks on similar roads and I find that this is about the average traffic flow during a normal working day, which shows that the East Riding has not been compelled to institute this exceptional service to meet exceptional circumstances.

What the "flying doctor" operation does do is to take the panic out of the situation. This is important, as the first principle when attending injured people is to endeavour to keep them calm. (How this can be achieved with lights flashing and sirens wailing escapes me.) The functions of the service are being examined constantly. Some are streamlined, others are extended. For example, recently the heads of the three services, plus the doctors, turned out on a disused road at a simulated accident to ascertain how they should park their vehicles to ensure the greatest efficiency.

Cab differences The expansion of the functions is exemplified in the way in which accident reports are analysed. Cause and effect are considered in detail. The accident involving the two hvgs to which I have referred showed the effect of a head-on collision on a metal cab and the quite different results with a glassfibre cab. The details were noted and these and other reports will result in recommendations to vehicle designers and builders. The loci of accidents is being studied and could result in useful reports to highway . engineers.

If this service should fail it will only be because of insufficient funds and not through lack of enthusiasm. What disturbs Dr Brown and his colleagues, who meet each month to discuss the service and analyse the accidents, is that only in the East Riding is there such a well-organized, comprehensive accident service.

Having watched the scheme at first hand, Lam convinced that it should be extended to operate on a national scale. One tipper operator with whom I discussed its financing was adamant in his views: "It's not only a very good scheme," he said, "but it is in my view an essential service and one which should be met out of public funds."

In the present economic climate and with the Government's avowed intention to cut public spending, I would think Treasury support for a national scheme is most unlikely to be forthcoming, and the continued success of the YERVAES will continue to depend on voluntary contributions such as the one donated by the Yorkshire (Hull) area of the RHA.

The expansion of the service, I fear, must also depend on charity. However, this could be forthcoming. Talking to a senior member of the RHA national executive committee about the Yorkshire (Hull) donation, I was surprised to learn that the committee had been perturbed to discover that the area had acted on its own. "This is something we want to tackle at national level," he said. How soon it will be tackled he could not say. In the meantime too many accident reports will continue to carry the macabre epitaph: Dead on arrival.